In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Battle for the Middle East

WEB EXCLUSIVE

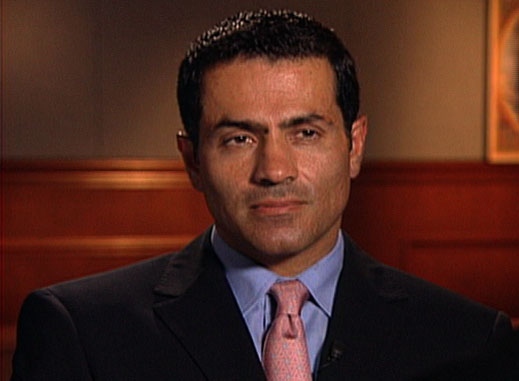

Vali Nasr

August 10, 2006

Read correspondent Lucky Severson’s August 7, 2006 interview in Washington, D.C. with Vali Nasr, a professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. He is also an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of THE SHIA REVIVAL: HOW CONFLICTS WITHIN ISLAM WILL SHAPE THE FUTURE (W.W. Norton & Company, 2006):

Q: Can you give a little history of the Shia-Sunni relationship going all the way back to Muhammad?

A: This is the major divide within Islam. It’s somewhat, you could say, like the Protestant-Catholic or the Eastern Church-Western Church divide in Christianity. It goes to the very beginning. When the Prophet Muhammad died, there was a dispute over who should be his successor. The Sunnis gathered as a community and chose the most trusted, the best among them as what came to be known as a caliph; whereas the Shiites, particularly over time, would dispute that method of choosing a successor, believing that the Prophet had a spiritual charisma. He was the chosen of God, and that charisma went through his bloodline, through his daughter who was married to his cousin, Ali, who is buried in the shrine in Najaf, and then through their progeny down to about the ninth century, when the last of this progeny was alive. They always looked at these imams, as they are called, as the true leaders of the community and believed that the Sunnis had erred by not following the progeny of the Prophet.

From this beginning-obviously much like Protestants and Catholics or the Eastern and Western Church-they diverged on how they practiced Islam. Shiites have a different ethos of Islam. There also are differences on matters of law, on practice, down to the point of how they stand at prayer. Each sees itself as the original orthodoxy. Neither one sees itself as an offshoot of the other one. But over time also this difference, just as in Christianity, has found political connotations as well.

At a high level, both are fairly legalistic, because Islam, like Judaism, is a religion of law that defines proper practice of Islam. But in practice, at the folk level in particular, Shiism is far more passionate and attached to rituals that are associated with the imams, who are like saints. In some ways, Shiism is more Catholic-like. It recognizes saints. It recognizes that there can be [an] intermediary between man and God. A Shia who goes to the shrine of Najaf in Iraq could be like a Catholic who goes to the shrine of Fatima in Portugal or the Virgin of Guadaloupe in Mexico.

The Sunnis are more Protestant-like. The Sunni cleric is more like a Protestant pastor, whereas a Shia ayatollah is more like a bishop or a cardinal, except Shiism has no pope. Just like Protestantism and Catholicism, both follow the same scripture, both follow the same story of Jesus, but they have a different ethos of Christianity. The same is true of Shiism and Sunniism.

Q: Why have these differences led to bloodshed? Why have they been that deep and divisive?

A: Because in histories of religions we know there are theological disputes. We know there are disputes over interpretation. These disputes among communities over time can lead to conflict. We had this history also in Europe. But also, in many periods of history, theological difference becomes a marker of identity, or it becomes politicized. For instance, when the Thirty Years War [was] happening in Europe between Protestants and Catholics, a lot of this was a power struggle between different princes over territory and independence from the Vatican and the like. Or when we look at Northern Ireland today, where Catholics and Protestants have been fighting for quite a long time, it’s not about whether you go to church; it’s about what side of the tracks were you born on, who you are, and where do you stand on the question of Irish independence and English presence in Northern Ireland. So the Sunni-Shia issue has the same kind of ebb and flow. It is about theology, but it also is a marker of communities. In Iraq today, why the Shias and Sunnis are so antagonistic is because, much like the Northern Ireland, the theological boundary marks the boundaries of different communities and their identities.

Q: So much of it goes back so far. The depth of feelings is not something that just happened in the last century.

A: It goes back centuries. First of all, history always, in religion, provides a symbol and a model so every religion can look back at historical episodes. For instance, Christianity in its early history had the catacombs and the story of the martyrs and the like. That looms large at times in terms of how it interprets history. Or the Jews have had a history of persecution, going back to the Roman period, which is very alive–the myth of Masada and the like–in the way they see themselves today. It is true of the Shiites as well. Shiites, in particular, have a history of persecution, because they were the underdogs. They lost to the Sunnis early on. Their various saints were killed. That’s why we have the shrines around them. The most important of them was the Prophet’s grandson, by the name of Hussein, who was killed at the battle of Karbala. He and 72 members of his family were killed by a far larger Syrian army that was sent from Damascus to subdue him, and the brutal way in which he was killed essentially galvanized Shiism. In fact, Hussein’s martyrdom is much like the crucifixion of Christ. It’s a seeming worldly defeat which leads to a far larger moral victory and is a moral example. Therefore, for the Shiites, the martyrdom of Hussein has an enormous amount of symbolism. So they interpret modern-day events in light of that historical model.

Q: Shiites refer to Karbala quite frequently. It was a watershed in the history of their fight with the Sunnis.

A: It was, but over history, for the longest period of time, Karbala had largely a moral value. It was a divine intervention in human history to symbolize truth. They shed tears every year during the ceremony of Ashura and beat themselves to basically partake in the suffering that Hussein suffered at Karbala, but as well to atone for not being there to help him when he stood up before a far larger military force of the caliph. But also, in the past two or three decades, particularly in Iran but also in Iraq, politicians as well as politicized clergy like Ayatollah Khomeini, like the late Iranian leftist Shia intellectual Ali Shariati-they use the myth of Karbala in the same way as in Catholicism in Latin America leftist theologians used the crucifixion of Jesus in interpreting liberation theology. So they reached out to an example historically where you have suffering and standing up to injustice in order to mobilize the poor in a current struggle. The current history has emphasized Karbala all over again, but in a much more political way.

Q: Ashura was not allowed when Saddam Hussein was in power. I don’t believe Khomeini even recognized it. But after the U.S. invaded Iraq, it was allowed. It’s a very important event for Shiites. What does it mean?

A: It is the most important event. Shiites may pray and fast and go to hajj and do the rest of the Islamic things the rest of the year, but this is the one event that defines them. It defines them because it separates them from Sunnis, but [it] also defines them because this is the time when they express their specific passion for Hussein and what specifically separates them from Sunnis. It is a dramatic event in which large numbers of people gather. They cry, they sing eulogies for Hussein, they beat their chests. Sometimes they draw blood, and they go into a frenzy. There is a lot of drama, dramatic, theatrical events associated with Ashura. The clergy have not always looked well on Ashura. They don’t condemn it, but they don’t condone its excesses either. Ashura is much more associated with the folk-level practice of Shiism.

In Iraq it was forbidden because Ashura has the quality of not only affirming Shia identity, which Saddam did not want to happen, but it brings large numbers of Shias together in a state of passion, frenzy, around the cause that was archetypal of the problem of Shias today, namely, facing injustice and tyranny. The example of Hussein is that he was courageous enough to stand up to it. So a Sunni dictator like Saddam did not want the Shiites to relive Karbala every year, and then to have two million people all together, which could always get out of control.

The very first impact of American presence in Iraq was not to give power to the Shiites; it was really to allow a Shia cultural revival. In other words, about a month or so after the fall of the Saddam regime, you had two million people showing up in Karbala and performing something they hadn’t been allowed for some time. That already announced that the Shiites were free to express themselves. That cultural freedom then translated into political power when they began to vote and identify as one community.

Q: Shrines are important to Shiites. Do Sunnis have similar shrines as well?

A: Yes, but not similar. First of all, in many parts of the Muslim world-for instance, in India or Pakistan, or in Egypt, or in Syria-many Sunnis, particularly at the folk level, do go to the Shia shrines. In other words, there has been a lot of religious cohabitation. For instance, the Egyptians believe that Hussein’s head is actually buried in Egypt. It’s at a mosque called Our Lord Hussein’s Mosque, right at the entrance to Khan Khalili bazaar, which is a major tourist attraction in Cairo, next to the Al Azhar Mosque. Many Sunnis visit there. Maybe they don’t venerate the mosque the way the Shiites do, but they go there with awe and respect. The Sunnis also have attended this shrine, but it is not associated with Sunni orthodoxy; it is associated with the spiritual tradition in Sunniism known as Sufism. In many parts of the Muslim world, such as in West Africa, in Morocco, in India and Pakistan, where great Sufi masters who were known as Sufi saints are buried, people believe that their shrines are a place where there is grace-baraka, as the Arabs call it. They do go visit these shrines even though it is in contravention to a strict Sunni view that there is no intermediary between man and God. They go there to receive grace. They go there to pray to God because they think that place is particularly blessed, or they go there to heal ailments and sickness and the like. Sufis actually understand Shia practices well, and the Shias understand Sufism at that level very well.

Q: Iraq has more than its share of important Shia shrines.

A: Iraq has more of the share of them because the majority of the Shia imams lived there and died there. Baghdad was the seat of the Sunni caliphate all the way until the thirteenth century. But there is also a very important Shia shrine in eastern Iran, in the city of Mashad, where one of the imams had taken refuge and was murdered there. There are about twelve million people who annually visit it, which makes it the second most popular site after Mecca in terms of Muslim visitation.

Q: What about the importance of martyrdom in both Shia and Sunni religions?

A: It is very important. For Shiites, before there was Ayatollah Khomeini, martyrdom was the way martyrdom is for Catholics; in other words, they respect those who gave up their lives to protect and perpetuate the faith. And they somewhat celebrated it-in the same way as the early Catholic saints wore the crown of thorns with glee and went to their deaths with open arms, in fact, even very much hoping to replicate the experience of Christ, having embraced his crucifixion. Shiites have the same view. All of their imams, and Hussein in particular, were martyred, so they have a very strong veneration for martyrs. They believe that one who is martyred goes directly to heaven.

Since the Iranian revolution, martyrdom was politicized. In other words, the Iranian regime of Ayatollah Khomeini openly tried to use this veneration for martyrs–dying for the faith–in service of protecting the Islamic Republic. Iran did so in particular during the Iran-Iraq war, where large numbers of Iranian youth basically used their bodies to defeat Iraqi armor, because Iran did not have enough war material.

Q: Tens of thousands?

A: Tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands.

Q: Some of them didn’t even have weapons?

A: Well, there weren’t weapons. In other words, Iran could not push Iraq out of Iranian territory without a conventional military, without international support and supply, so it basically resorted to mobilizing large numbers of people, who basically ran onto Iraqi positions and then Iraqi minefields. The Iraqi army could not deal with this swarm of human-wave attack and began to withdraw. Then this doctrine was adopted by Hezbollah in Lebanon, where you went from large numbers of “martyrs” attacking a conventional military to individual martyrs tactically and strategically attacking Israeli forces.

Q: The suicide bombers?

A: At that time, they were called martyrdom missions under Hezbollah, but they were very successful. They pushed Israel out of Lebanon. Some six-seven hundred Israeli soldiers died, and also it was used in attacking the U.S. marine barracks and the French military barracks in Beirut in the 1980s. At that time, everybody thought that martyrdom is the monopoly of Shias, that the Sunnis would never do it. In fact, there is a story that throughout the Afghan war, you couldn’t find an Afghan suicide bomber who was willing to kill himself in the middle of the Salang tunnel that connects northern Afghanistan to Kabul, because the only way to shut down the tunnel was to have somebody go in the middle of it and kill himself. If you did it at either end, you could clear it up easily. And you could not find anybody who was willing to do that, Arab or Afghan. But gradually, Arab radical Sunni groups-Palestinians as well as Al Qaeda-came to a theological shift to embrace what they had seen in Hezbollah and make it their own. So whereas the conventional wisdom was that the Sunnis would never do the things Shiites do, we saw that they actually adopted the things the Shiites do at the very time that the Shiites stopped using it.

Q: It really came about under the leadership of Khomeini?

A: It came under the leadership of Khomeini, but one should be careful that this was not always religious. In other words, the very first suicide bombers-out of the very first fifty suicide bombers that Hezbollah used, only a handful were Shiites. Among them were Christian women. There were Communists and Marxists and Arab Socialists. In other words, even though the rubric always was that the Shiites do this because of their belief in martyrdom, you already had the germ of this becoming a favorite tactic of insurgents vis-a-vis far more superior military forces.

Q: You write that during the Iran-Iraq war, the longer Khomeini was in power the more he assumed the venerated position of the twelfth imam, and to inspire these tens of thousands of unarmed troops, he would actually send a shroud on a white horse in the middle of the night through them.

A: Religion at the folk level is less about proper practice and is much more passionate and attached to myths, particularly saints and the like. In other words, ghetto Shiism, if you want to call it–street Shiism–is very much like Catholicism of the barrios of Rio de Janeiro or Sao Paulo, where there are a lot of practices that are much more about passion and faith and personal attachment to saints than they are about the high moral and legal code of religion. Within the Shia communities everywhere, there is a tremendous attachment to the myth of the Shia messiah, the hidden imam. Sunniism does not have a messianic doctrine. The Shia messianic doctrine is very close or similar to the Judaeo-Christian messianic doctrines. There is the expectation of a second coming of the twelfth imam. Therefore, the Iranian regime under Ayatollah Khomeini, and even it is doing it today under President Ahmadinejad, uses this popular level, folk-level attachment to the myth of second coming in order to mobilize the population for various political or military activities.

Q: Tell me about the origins of Wahhabism.

A: That came as a form of reform out of Saudi Arabia, what then was the Arabian peninsula, from the inner territories which is now the Naj plateau, as it is called, the interior of Saudi Arabia. The Saudi coast was always much more cosmopolitan, an area where trade happened, where pilgrims went. But the interior was inhabited by nomads, and the form of Islam that was practiced there had a lot of non-Islamic elements in it. Wahhabism emerged as a puritanical movement of reform, to clean Islam from what it saw to be un-Islamic. But in practice, it is very much of a bedouin, desert, black-and-white view of Islam. It does not leave much room for interpretations. It is highly legalistic. It does not believe there is any intermediary between man and God. It is about “thou shalt” and “thou shalt nots” of Islam, but interpreted very narrowly. It is highly intolerant of any kind of deviation from what it sees to be the correct path. Wahhabis don’t even accept other Sunnis as practicing religion properly, and then they view Sufis or Shiites as completely outside the pale.

Q: The Saudis funded this movement. Was it also in part to curb concern about Shiite influence?

A: Saudi monarchy is Wahhabi; in other words, the Saudi regime arose in the early 1900s, 1913 onwards, with the conquest of Arabia all the way till they established the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, as a marriage of the Saud tribe with the Wahhabi religion, so this is a marriage. Saudi Arabia is a marriage of this faith with that family. The political and military triumph of that family made Wahhabism essentially the official religion of Saudi Arabia. The two are joined at the hip together. But from 1970s-1980s onward, as the monarchy began to become more westernized and more entangled with the United States, a gradual breach began to open between the monarchy and its Wahhabi allies. One of the ways in which the Saudi monarchy dealt with this was to begin to fund promotion of the Wahhabi view of Islam outside of Saudi Arabia. This also had traction because, as Saudis came into money, they liked to make themselves the center of the Islamic world. As the center of the Islamic world, they began to propagate their Islam as the Islam. A lot of money went into propagation of Wahhabi views.

Once Khomeini took over Iran, Wahhabism seeing Shiism as heretical was the best vehicle for creating an ideological-religious wall around Iran. The more Khomeini tried to say that he is the Islamic leader, the more Saudi Arabia and its Wahhabi allies and their allies in the rest of the Muslim world began to say, no, no, no, you are a Shia. You cannot be our leader.

Q: When the U.S. attacked Iraq and gave the Shias more prominence there, that must not have pleased the Saudis.

A: It didn’t, but you see, the Iraq war also happened at a low point in U.S.-Saudi relations, because the events of September 11 implicated the Saudi monarchy in having supported the Taliban and the charities and networks associated with the Kingdom in having supported terrorism. Even in a best-case scenario, Saudi Arabia was seen to be somehow a bastion of conservatism, part of the problem rather than the solution. Much of the planning for the Iraq war happened during the moment of Saudi Arabia’s weakness in Washington. The so-called neoconservatives were also highly critical of Wahhabism. They saw Wahhabism as part of the problem. Therefore, Saudi Arabia was not able to exert the kind of influence it had traditionally in forming U.S. thinking on the Middle East during that critical time period.

Q: Did the Taliban embrace Wahabbism?

A: The Taliban were not Wahhabis technically. They came out of a very old tradition of Islamic learning in South Asia. But they gradually began to practice their own religion in increasingly puritanical ways that basically created a convergence with Wahhabism. Even though the Taliban were not officially followers of the Wahhabi branch of Islam, their practice of Sunni Islam is very close to that of Wahhabism. They are also highly puritanical.

Q: When the U.S. attacked Iraq, Saddam basically accused the Shia of sympathizing and helping the U.S., just as they had helped the Mongols when they invaded Iraq in 1258.

A: That’s right. In other words, often the accusation in the Arab world is that the U.S. started sectarianism by appointing an interim governing council along sectarian lines-assigning numbers to Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds. That’s a fallacy. First of all, for the last decade of Saddam’s rule, between 1991 and 2003, his government had become increasingly sectarian, because after the first Gulf War you had a Shia uprising in the south, which was brutally suppressed. Hundreds of thousands died or lost their homes…

Q: …because they thought the U.S. would come to their aid.

A: In fact, all of these mass graves that are found in southern Iraq were largely the legacy of that campaign. After that, the Iraqi state became much more clearly sectarian. The Sunnis had to suppress the Shiites to rule, so you had this prelude. Then Saddam basically-and other insurgent leaders like Abu Musab al-Zarqawi-began very quickly identifying the Shiites with the Americans. Saddam basically tried to exonerate his own feeble protection of Baghdad, resistance to the fall of Baghdad, by saying that the Shiites collaborated with the occupier and they are, therefore, traitors to the Iraqi nation and to the Muslim nation. He says this in a colorful way by comparing Bush’s or America’s conquest of Iraq with the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in 1258 and then compares President Bush to the Mongol ruler Holagu. Then he compares the Mongol vizier, Ibn al-Alqami, with the Shiites. Ibn al-Alqami historically is accused of having opened the gates of Baghdad to the Mongols. The fall of Baghdad is a momentous event in the Muslim political psyche, because it is the end of the real caliphate, so it has symbolic meaning. Saddam was very cleverly making his own defeat have momentous Islamic symbolism. But with a clever twist, he was also assigning the Shiites the negative role that he wanted to assign them in this sort of historical drama.

Q: Many in America haven’t appreciated how deep the Shia-Sunni division within Islam goes.

A: Actually, we haven’t yet realized the consequence of this violence. These days, we talk about civil war and we talk about Shia militias and Sunni insurgents each being equally as bad as the other. But we forget that, for the first two or three years of our presence in Iraq–that is, up to February 2006–the Shiites largely did not respond or retaliate. They were essentially accepting these suicide bombings and killings on a continuous basis. It’s only when the shrine of Samarra, which is where two of the Shiite imams are buried north of Baghdad, was destroyed in February 2006 that something snapped among the Shiites. They began to hit back and create a balance of terror in Iraq.

For the longest time, the Sunni violence against the Shiites, their refusal to accept the cultural revival of Shiism, and the assumption of power in Iraq by the majority Shiites set the tone for the conflict in the region. We didn’t see this for what it was. We tried to ignore this fact. I would hear all the time people saying, well, you know, Iraqis are too intermarried, have too much history together, and this is not going to take root. Not only has it begun to take root, but it’s also coloring Shia response to power in Iraq. It is coloring Hezbollah’s behavior in its own arena of political conflict. It is impacting the way Iran is calculating its opportunities. In other words, we had two events that happened that are critical. There was the Shia revival at the beginning, which was a momentous event. Then there is the Sunni reaction to it, which is another momentous event. The Sunni reaction has been quite violent in Iraq, and that doesn’t serve as a good omen for the region.

Q: Wasn’t the Shia reluctance to get involved primarily because of Ayatollah al-Sistani? He has been a very moderating voice, compared to Muktada al-Sadr. Tell me about these two men.

A: Ayatollah Sistani is like a senior cardinal in Iraq. In other words, he is the most revered and respected senior ayatollah in Iraq. Ever since the fall of the Iraqi regime and the opening of Shia southern Iraq, he’s actually gained far more popularity outside of Iraq-in Iran, in Pakistan, in Kuwait, in Lebanon, in the diaspora Shia communities. He is what you call a quietist. A quietist historically in Shiism means that it is the job of the ayatollah to protect the community and its interests and its identity.

But he does not have a claim to rule, nor does he claim to know what is the best form of government. He rather operates by veto, so a government is good so far as it protects Shia faith and community and does not violate Islamic law. Sistani abided by that model. But also he very early on understood that this is a historical opportunity for Shiites to assume control of Iraq.

Elections, democracy, “one man, one vote” benefit them. They should not embrace violence; they should embrace the political process, because violence should be the method of those who gain no benefit from the political process, which in this case were Sunnis, because political process in Iraq would actually ascribe to them what should be their due in accordance with their numbers, which is to be the third community in order-Shiite, Kurd, and then Sunni Arab. Sistani’s argument was that the Shiites once rose in rebellion against the British in 1920. They paid the price. The British gave the keys to the country to the Sunnis. They shouldn’t do that. They should remain focused on the alternate path. But as the Sunni violence against the Shiites escalated, as Shiites died in marketplaces and were assassinated, and Shia policemen and officers were killed as recruiting lines were attacked by Sunnis, [Sistani] began to lose authority. The coup de grace essentially came when the shrine in Samarra was destroyed. The Shiites’ argument was you cannot coexist with them. They are going for the jugular. They are destroying your holiest holy sites. Ayatollah Sistani’s call of restraint, his turn-the-other-cheek strategy is being construed by Sunnis as weakness. You’ve got to answer force with force. So from the bottom, from the street, from the militias arose a different Shia response, which was disdainful of Sistani’s quietism. Basically, it began to take the fight to the Sunnis, to establish a balance of terror in Iraq. The Shiites began to assassinate, torture, kill, kidnap, and attack Sunnis as well. What you ended up with was you went from a situation of one community trying to provoke the other one to now having a cycle of violence as the other community eventually engaged. Sistani continues to call for calm, but his voice is fainter than it was two years ago.

Q: And Muktada al-Sadr?

A: His [voice] has become louder, for a variety of reasons. One is that he has a base of support among the street poor in Sadr City and southern Iraq and the like. He has some attraction for those who view him as being a son of soil, of having been there, his father having been there, having claims to a united Iraq, being critical of the United States–unlike the other Shia groups. But, also, Muktada has been building power and building his resources ever since the fall of Saddam. He has been investing in community, in social services as sort of a Hezbollah model in Iraq. He has become a growing force, both a military force on the ground-he has a very big militia, the Mahdi army-but he also has representation in the parliament. He has held onto cabinets, council positions. He is a political force on the ground as well.

Q: And he has an entirely different view of religion than Sistani?

A: Yes. His father was closer to the Iranian model. Initially, he actually was supported by Saddam to become an ayatollah, as the alternative to the ayatollahs of Najaf. But at some point, he made a turn. He focused on the poor, on mobilizing the poor, the migrants who came out of southern Iraq and settled in shanty towns and the like. He helped them; he gave them social services. But also he had much more of a combative view of Shiism. He appealed to the myth of the hidden imam, of the twelfth imam, messianism. He believed in a socially engaged Shiism. He even began to toy with the ideas of Ayatollah Khomeini. In fact, the Saddam government probably killed him the moment that he declared something like Khomeini’s idea of velayat-e faqih, “guardianship of the jurist”–the idea that there is a supreme ayatollah that has command of not only religion but of community. The minute Muktada al-Sadr’s father made that proclamation, he was a marked man, and eventually Saddam assassinated him and killed also his two elder sons. So Muktada comes from that tradition. He is also not very well educated. He is not a genuine cleric. The establishment clerics often refer to him as an ignorant child. They always were disdainful of him, dismissive of him. He also is dismissive of that whole scholarly tradition. When he was young, many even in his father’s movement say that his father didn’t take him seriously. He was the fourth son. There are people who say that he is unstable mentally, that he has a bipolar personality, that he is manipulated by people around him. He was never a good seminary student, never finished his work, used to play a lot of video games when he was a youth. But in some ways he has surprised a lot of people, because not only has he survived, he has gained in power, and he’s proven himself to be politically savvy.

Q: Imam Shariati, not unlike Khomeini, taught that you shouldn’t sit idly by waiting for the twelfth imam, but you should hasten his return; you encourage fighting so that it will bring on the end. Are there also similarities in this sense between Khomeini and Muktada al-Sadr?

A: In religions that have messianism–this is true of Christianity as well and Judaism–there is a difference between those who really believe that the messiah can be brought faster, so you are looking to create the Rapture, you are trying to create Armageddon–there is a difference between that and Khomeini or Shariati. Khomeini or Shariati were not trying to bring the messiah; they were trying to use him and his image. Also, they were trying to justify what they were doing. Let me put it this way. Much like Judaism, in Shia Islam it is the job of the messiah to set things right. Things are supposed to be bad until he comes. In fact, they are supposed to get worse before he comes. So if somebody comes along and says, I am improving things, I am creating actually a perfect order in Iran, well, the answer should be: Who are you to do that? That’s the job of the Messiah. So the way Khomeini or Shariati answered, they said, no, no, no. We are hastening his coming. Actually, in Judaism there was a similar response. When the Zionist movement created Israel, many Orthodox Jews said the return of Jews to Palestine is the job of the Messiah, so secular Zionists are taking onto themselves the duty of the Messiah. The conservative Orthodox Rabbi Kook [1865-1935] and his son basically created that bridge by saying that Zionism is not in violation of prophecy; it is hastening prophecy. Zionists are not fulfilling the messianic mission; they are merely bringing it closer by bringing Jews one step closer to where they ought to be. That’s the kind of argument that Khomeini and Shariati were putting forward. They are not imminent messianists; they were not waiting for the imminent appearance of the messiah. They were, rather, trying to justify a political revolution and movement that seemed to be running at odds with the Shia prediction that the perfect Shia order will be brought about by the messiah.

Q: Does the new leader of Iran, President Ahmadinejad, follows Khomeini’s interpretation? Is that what he believes?

A: To some extent. There are many things in Khomeini and Shariati, particularly Khomeini’s reading of Shiism. First of all, Khomeini was a populist revolutionary. Ahmadinejad is also a populist revolutionary. Khomeini, though, was not interested in playing folk Shia practices. He never participated in an Ashura. He never went to a shrine. Even though he used the title “imam” and appealed to messianism, he did not like folk-level messianism, whereas Ahmadinejad does play to the folk-level messianism by claiming to have seen light at the United Nations and that the hidden imam appeared to him there and the like. So there is a difference. But one of the very interesting breaks is that Ahmadinejad represents an anti-clerical trend in the Iranian revolution. This was a revolution that brought the clergy to power. The entire doctrine that Khomeini had was premised on the rule of the clergy, whereas Ahmadinejad very subtly is asserting the role and power of the revolution’s non-clerical children. When he was running for president, he constantly said my campaign is that of the university versus the seminary. He characterized the leading ayatollahs of Iran as being soft and corrupt. His generation of lay Revolutionary Guard veterans and the like really are now the repository of the revolution. Even when he went to the United Nations and supposedly saw the light of the messiah there-and then there was a DVD in Iran that showed him narrating this story to a very senior Iranian cleric-the point was not that he saw the light, I think; the point was that he was telling this to a cleric. Clerics are the guardians of the messiah in his absence, so here is a lay president saying that he’s seen the messiah, not the cleric. And the Iranian presidency under him can serve as the guardian of the legacy and the function of the messiah, not the clerics. Some Iranians within the conservative camp even referred to him as a Luther figure. In other words, we shouldn’t be just completely mesmerized by his radical vocabulary and his hard-line revolutionary attitude. Underneath that, he represents a tension between clerical rule versus lay revolutionary rule.

Q: Is that good?

A: It depends what the outcome is. In many ways, Ahmadinejad is asserting his power through the office of the presidency in Iran. He’s trying to strengthen the presidency–what his predecessor couldn’t do. This ultimately will lead to a major tension with the supreme leader in Iran, because this is about power. Is he willing to give up powers to the presidency? It doesn’t matter whether he’s a reformist or a conservative. Is he willing to give up executive powers to the presidency in Iran after he had so successfully taken it away under the previous president? I think ultimately that could be healthy for the Iranian system, because it can bring to the fore a lot of the issues that ought to be debated in Iran and are not being debated because the regime has a facade of unity, particularly vis-a-vis the West.

Q: How important to the future of Iraq is Iran?

A: Enormously at this point, because Iraq is currently extremely unstable. The Shia community of Iraq, so long as they feel enormous amount of insecurity towards U.S. intentions and towards coexistence with Sunnis, are likely to look at Iran as an ally, as a patron. Iranians similarly are extremely concerned about what the outcome in Iraq will be. Will the Shiites easily dominate? Will there be a prolonged civil war? Will Iran be sucked into that civil war? Will it precipitate a conflict with the U.S.? In many ways–at least as far as the Shiites and the Iranians are concerned–in the near future the future of the two countries depends on the outcome in the other one.

Q: Hezbollah is mostly Shiites being supported by Iran, and they have been all along. Can you resolve Hezbollah without bringing in Iran and Syria?

A: In the short run, I don’t believe so, because you are trying in the short run to deal with a military conflict, and you have to deal, in stopping a military conflict, with those who are participants in the conflict and those who have a vested interest in its outcome. We already have identified–and so have Israelis and so has Saudi Arabia–that Iran is a major player in this. That doesn’t mean that Iran picked up the phone and ordered Hezbollah to do this. We don’t know that. What we know is that Iranian weapons, Iranian money, Iranian training, Iranian strategic support accounts for what Hezbollah has done and is capable of doing. Therefore, ultimately, to have a lasting ceasefire, a lasting cessation to military conflict, you have to talk to Iran and Syria at some level, in some way. They have to have a vested interest in that ceasefire. More long run, I think dealing with Hezbollah and the problem of Hezbollah in Lebanon requires a broader political solution, both to Lebanon’s internal problems-confessional problems, political system problems-but also the regional problem between the U.S.-Iran and Israel and Iran.

Q: If it continues going the way it has, Hezbollah is gaining more and more prestige; Shias are gaining more and more power. That can’t please Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Israel. The only thing the Shias and the Sunnis seem to be able to come together on is Israel.

A: At least in the short run that’s true. You know, the Arab world in recent years is suffering from an accomplishment deficit in some ways. Particularly the way the Saddam regime fizzled has created a problem. If you look, Hezbollah has defended that little border village, Bint Jubail, far more valiantly than Saddam defended Baghdad. The fact that Hezbollah is willing to take on Israel is popular on the Arab street. Hezbollah’s actions have also diverted attention from the Shia-Sunni issue in Iraq to the Palestinian-Israeli issue in the Levant. That is a unifying force. It doesn’t mean that Shiites or Hezbollah will continue to enjoy unquestioned support on the Arab street, but in the short run it means that Iran and Hezbollah have essentially hijacked the Palestinian cause. So it’s pointless to try to work through the old mechanisms and agreements and countries to bring immediate stability to this issue. You have to deal with those who are now holding the cards. This is Hezbollah, Syria, and Iran. Also, this war has had a certain logic of its own. One is that the outright military superiority of Israel has not solved the problem. Israel so far has not been able to achieve the goals that it set for itself in the first week, which is to destroy Hezbollah and disarm it and the like. So if military force is not going to accomplish this, and you don’t want to have a protracted, ongoing lobbing of rockets into Israel and Israeli attacks in Lebanon, you have to find a framework that you could have a sustainable ceasefire. It seems to me that, in the short run, that has to happen by having your protagonists–which is the Iran-Syria-Hezbollah axis–having a vested interest in the ceasefire, not the rest of the Arab world.

Q: If you look at the Middle East overall, it all just seems to spell disaster. What can be done to prevent disaster? What can the U.S. do?

A: You have three major conflicts now going on, all of which are interconnected. You have a conflict over Iran’s nuclear issue, which can potentially turn into something much worse. You have the near-civil war sectarian conflict in Iraq, which could potentially be highly destabilizing to that country and the region. And you have the conflict in Lebanon. Now, all of these involve Iran as a major player. All three of them are also rapidly destabilizing the regime, creating anti-Americanism, bringing volatility, destabilizing governments friendly to the United States, and probably ultimately supporting militancy, terrorism, jihadism and the like.

I think the first order of business for the U.S. ought to be to bring immediate stability. In other words, protracted, cascading conflicts that are interconnected and go from one to the other and feed on one another are going to stretch the U.S. and are going to ultimately overrun its capabilities. It creates outcomes that we cannot possibly forecast and [that] can be very dangerous. We want to avoid those. We don’t want to have enveloping conflicts of the kind we are seeing, so we need to find ways to stop these conflicts and at least bring a modicum of stability to the region in very quick order before it gets out of control.

Q: Do we need to talk to the Iranians and to Hezbollah? Do we need to talk to Syria?

A: Some of these would be necessary. In other words, we have to take stock of the reality of the region. The alliances we used to work with are important, but only now in certain segments. In key areas in Iraq and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict now, Iran holds major keys, as does also Syria. Either there is a military solution to this–I don’t believe there is a good military solution to this problem–or we have to find a diplomatic one. Diplomacy, by definition, should be with your adversary. Engaging Iran or Syria does not mean recognizing them. It does not mean accepting their regimes, does not mean giving them a green light to continue to behave badly in the region or to suppress the Iranian population. It means, rather, that you open a door to be able to talk about some basic concerns of the U.S. and be able to reach agreement on those concerns, based on a give-and-take. It’s like the way we dealt with the Soviet Union. We fought a war against them in Afghanistan. We supported the mujahadin against them. We supported dissidents in Eastern Europe, but we also were engaged in detente and other conversations with them. Ronald Reagan could call the Soviet Union an evil empire and yet meet with Mikhail Gorbachev and try to push for U.S. interests-get the Soviets to give up on things that mattered to the U.S. And then the U.S. sometimes had to give up things as well. I think it would be very difficult for us to deal with the Middle East only through the military option.

[Not talking to Iran and Syria] makes management of the region much more difficult. We are also at a time when we are thinking about the costs of the way in which our involvement has unfolded in the region. There are military costs, diplomatic costs, energy costs. The lesson of the Lebanon war is that there is no easy military solution. Israel has not been able to easily and in a cost-free and quick way deal with Hezbollah. As a result, it behooves us to consider other options. Also, we have to sit down and think what is it that most immediately we want from Hezbollah, Iran, and Syria? Obviously, [in the] long run, we know what we want: We want them to disarm, change their behavior, practice domestic freedom, engage in political reform, and give up on nuclear power in the case of Iran. But the most immediate thing we want from them is to be able to bring stability in zones of conflict in the region. I think there is room for us to explore if there are diplomatic options to demand what we want and see whether we can engage those countries in behaving and contributing to stability in the region.

Q: You write that “the lesson of Iraq is that trying to force a future of its liking will hasten the advent of those outcomes that the United States most wishes to avoid.”

A: I think Lebanon is a very good case of that. Even though we didn’t start this, we’re not the ones doing the war in Lebanon, Israel is following very much the model we set out in Iraq, with the idea that shock-and-awe can redraw the political map of the region. I think we are seeing that it is counterproductive. It has a public relations cost in terms of international cry against civilian deaths and the like. It is politically and militarily costly domestically to engage in these kinds of wars. They don’t have a result, and they can actually be counterproductive, because you actually end up strengthening your adversary, who thrives on your inability to finish it off. Israel may have wished a particular outcome out of the Lebanon war. The outcome it gets is maybe the one it really didn’t want at all.

Q: Looking at the divisions between the Sunnis and the Shias, what do you think are the chances of the sectarian violence in Iraq becoming a civil war?

A: I think in Iraq the chance is extremely high, because I think both communities are moving in that direction. There is not sufficient force on the ground to forcibly separate them out and impose peace on them by force. The scale of killings, the ways in which communities are being cleansed on both sides, is all suggestive that you either are at the very first stages of civil war, or that you’re having essentially both sides posturing for what might be a final showdown. You already have a battle for Baghdad going on, where each side is trying to get the upper hand in control of territory and power in Baghdad. The question really is whether it continues at this pace of a hundred [civilian deaths] a day or so until the dust settles and the two communities are pretty much separate, or you are going to have at some point a big blow-out, Yugoslavia-style, where you are going to have a much more violent conflict occurring before things simmer down.

Q: Is there any hope for democracy in Iraq?

A: Not until this particular cycle of political and military competition between the countries is settled. In other words, democracy in Iraq requires an agreement over the political community, which doesn’t exist. The Shia see themselves as Shia, Sunnis as Sunnis, and Kurds as Kurds. We saw this in multiple elections in Iraq. Secondly, it needs a modicum of peace and stability, law and order. Thirdly, it needs a widely accepted constitutional framework around which the rule of law, the give-and-take of democracy in a distribution of power ought to occur. All of these are lacking in Iraq. What you had in Iraq is elections, which turned out to be ethnic and sectarian referendums. You don’t have a constitution that there is agreement over. In fact, the Sunnis have rejected and don’t want to participate. You don’t have a definition of political community, because the Kurds don’t want to be part of Iraq, really; they want to be just nominally included in Iraq, but not be part of Iraqi society. The Sunnis are not accepting of a Shia-defined and Shia-dominated Iraq. And you also don’t have law and order. How can you practice everyday mechanics of democracy without having law and order? What you have is actually the opposite. Rather than political parties becoming stronger, you have militias that are becoming stronger. Rather than cross-sectarian, cross-ethnic political parties emerging, it is the highly sectarian, highly ethnic political parties that are dominating. One would hope for democracy-that it would come at some point. But in the immediate future, I don’t see it in the cards. I think the tendency of Iraqis is increasingly to ask for basic law and order and basic stability in Iraq.

Q: Over the centuries it seems Shias have generally been treated as second-class citizens by the Sunnis, who far outnumber them.

A: Particularly in the Arab world. In Iran, obviously, they’ve been ruling. In Azerbaijan, they were a majority even under the Soviets in their own republic. In Pakistan also, even though they were a minority, for a long period of time before hard-line Sunni ideology came to Pakistan, they were part of the ruling classes. The country was created by a Shia. You had Shia prime ministers. You had Shia governors-general. Even today in Pakistan Shias are part of the elite, but you have a gradual shift ever since hard-line Sunni ideologies come. But in the Arab world they were always excluded from power. It doesn’t matter whether they had the numbers or didn’t have the numbers; they weren’t part of the political community.

Q: And that is changing now.

A: That is changing now for two reasons. One is that demographics has favored Shias in recent years. In other words, particularly being among the poor and the downtrodden in places like Iraq and Lebanon, they proliferated much faster. In fact, in Lebanon, one of the anti-Shia biases of the more debonair Sunnis and Christians is that they procreate too much. But the realities of the numbers have grown. So at some point, you would reach a tipping point, where a majority or a sizable portion of the population cannot be suppressed the same way. But, secondly, Iraq provided changed political expectations of Shias. For the first time, they saw it is possible to rule; it is possible that the old calculus can change. Much in politics is about when one side comes to believe that certain things that were impossible before are now possible. The lesson of Hezbollah’s showing in Lebanon is to also show that the Shias have the ability to be a regional power. They are the ones who have the capability and courage to take on the Israelis, not the Sunnis. They are redefining the Arab-Israeli issue. This sense of empowerment among the Shias, both in Iraq through voting and with Hezbollah through its tackling of the Arab-Israeli issue-you have a sense of the Shias believing they have arrived. They have a right to a seat at the table within their own countries, but they also have a right to a seat at the table regionally. It doesn’t hurt this attitude in the Arab world that Iran also happens to be the most powerful country in the region right now. That obviously feeds this perception.

Q: Thanks partly to the U.S.

A: Thanks partly to the U.S. Iraq also, thanks partly to the U.S. In Sunni eyes, this is a bad thing, but I don’t think in Shia eyes this is necessarily a bad thing. After all, when we went into Iraq, at that point the Shias were not engaged in Al Qaeda, they were not attacking the Twin Towers, they were not being recruited by jihadi Web sites. Even if their rulers were anti-American, the Shia populations in Pakistan, in Iran, even in Lebanon, you could say, were either more neutral or even pro-American in places.

There was a moment where the U.S. could have built on this initial goodwill–that whatever its faults, it happened to open the door for the Shiites. But the conflict with Iran and the conflict with Lebanon may be very rapidly closing the opening that existed.