Pope’s Trip to Turkey

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Pope Benedict XVI wrapped up his four-day trip to Turkey Friday (December 1). It was a major diplomatic mission as well as a religious one to the one-time capital of Christianity. Turkey is now officially secular but almost entirely Muslim. Kim Lawton reports from Istanbul.

KIM LAWTON: It was a trip surrounded by both ancient and very recent animosities as Pope Benedict XVI came to this crossroads between East and West. He called this “a mission of dialogue, brotherhood and reconciliation,” and in his first visit to a predominantly Muslim country, the pope took every opportunity to express his respect for the Islamic faith.

Pope BENEDICT XVI: Christians and Muslims following their respective religions point to the truths of the sacred character and dignity of the person. This is the basis of our mutual respect and esteem.

LAWTON: It was a message clearly intended to calm the tensions generated two months ago by his speech at the University of Regensburg in Germany. There Benedict quoted a 14th-century Byzantine emperor who criticized the Prophet Mohammed and accused Muslims of spreading their faith by the sword. The speech ignited a firestorm of protests across the Muslim world. The pope later said the quote did not reflect his personal beliefs, and he expressed his regret for causing offense. But he never apologized for using the quote.

Here in Turkey, Benedict did not directly mention the speech. But he listened as the head of the Turkish religious affairs office made a reference to recent Islamophobia, which he said wrongly promoted the notion that Islam encourages violence.

Many local Muslims were impressed by how Benedict handled the official’s comments.

KERIM BALCI (Columnist, ZAMAN Newspaper): This was a critical moment. If I was the pope, I would turn back and say something, because it was quite critical and harsh. And the pope was patient, and I think the pope did something good by keeping quiet — not by speaking.

LAWTON: Kerim Balci is a columnist at Turkey’s largest newspaper, ZAMAN, which promotes Islamic values in its advertising and editorials. He says he was also pleased the pope acknowledged that Muslims and Christians believe in the same God.

Mr. BALCI: When the pope said that Muslims, Christians and Jews do believe in the same God, this is something new. Even the previous pope wouldn’t dare say that okay, we do believe in a God, but the same God? It’s something new.

LAWTON: With the protection of a massive security force, Benedict visited two historic and revered sites in Istanbul. For Muslims and Christians alike, this was a symbolic high point of the trip. First, he went to Aya Sofia, a nearly 1500-year old symbol of Muslim Christian tensions. Built in the sixth century, Aya Sofia or Holy Wisdom was the most important basilica in Christendom until the sack of Constantinople in 1453. The conquering Ottomans turned it into a mosque, which it remained until 1935 when secular Turkish officials made it a museum.

Then Benedict went to the nearby Blue Mosque, a stop added to his itinerary at the last minute. The early 17th-century structure is known around the world for its beautiful blue tile work. Benedict is the second pope to visit a mosque. Following Islamic practice, he took off his shoes before entering. He was accompanied by Istanbul’s leading clerics, and he observed a moment of prayer, a gesture widely praised by Turkish Muslims.

JOHN ALLEN (Senior Correspondent, NATIONAL CATHOLIC REPORTER): The top aim of this trip from the Vatican’s point of view has been to re-introduce Benedict XVI to Muslim public opinion as a friend and to some extent, it would seem that it’s been working.

LAWTON: Tens of thousands of people protested in streets of Istanbul before the pope arrived. But his visit appeared to go over well with average Turks.

This man told us the pope is trying to create a connection between Muslims and Christians, even though he’s actually hurt Muslims in the past. And this woman said she thought the pope did a good job here. She said she would have liked to pray with him in the mosque.

Many here were very pleased after the Turkish prime minister said the pope indicated he would support Turkey’s admission to the European Union. It was a surprising turnaround. As a cardinal, Joseph Ratzinger had opposed the admission on the grounds that Turkey does not share Europe’s Christian culture.

Although Benedict may have changed his position on that issue, he is not likely to soften his hard-line positions on other points of tension.

Mr. ALLEN: I think there is every indication that Benedict XVI intends to continue to demand that Islamic leaders and other religious leaders denounce violence in the name of God, and also that majority Islamic states, those 56 Muslim states on Earth, do a better job of protecting the religious rights of their minorities.

LAWTON: Experts say how this visit is ultimately seen by Muslims and Christians will have a major impact on the rocky state of interfaith dialogue around the world.

JOHN ESPOSITO (Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding): It’s important to remember that in Muslim countries the pope is not only a symbolism of Catholicism. In many ways, they don’t distinguish between Catholics and Protestants. He is Christianity. I think that this is an opportunity precisely because it’s a risky moment. You know, when you have the risky moments, that is when you can also have the greatest opportunities.

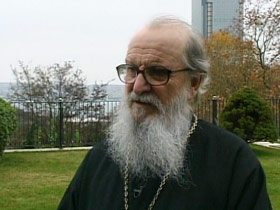

LAWTON: While tensions with Muslims dominated much of his visit, the pope’s original reason for coming here was to try to repair a rift with Orthodox Christianity which has lasted more than a millennium.

After centuries of disputes, Christianity split between East and West in the Great Schism of 1054. Latin-speaking Western Christianity developed a centralized church structure headed by the pope in Rome, while Eastern Orthodox churches organized regionally under the spiritual leadership of an Ecumenical Patriarch who was considered “the first among equals.”

The current Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, who is headquartered in Istanbul, invited Benedict to celebrate the Feast Day of Saint Andrew, the apostle who brought Christianity to Asia Minor. The two leaders participated in several worship services together and held closed door meetings. They released a joint declaration renewing their commitment to work toward restoration of full unity between the two churches. Representatives of both churches said this was part of an ongoing process of dialogue.

Bishop BRIAN FARRELL (Pontifical Council for Christian Unity): Catholics and Orthodox are committed to the goal of unity in diversity. This visit therefore is all about the healing of memories of past offenses and building bridges of understanding.

Archbishop DEMETRIOS (Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America): It has been a constant marching together for a closer and better understanding and cooperation.

LAWTON: But Archbishop Demetrios, leader of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, admitted that full unity won’t be achieved anytime soon.

Archbishop DEMETRIOS: We have been separated for a thousand years. A thousand years is a big time span, and if something quick happened, we would be very suspicious that something is wrong here.

LAWTON: Significant obstacles remain — questions over how much authority the pope should have and theological differences over the nature of the Holy Spirit. Still, the two churches promised to work together on other issues.

Archbishop DEMETRIOS: The unity as an ultimate final goal is something that has to stay alive, focused, and visible all the time. But at the same time we have to have the patience to work diligently towards this end and enjoy anything that is in between.

LAWTON: Benedict’s visit was encouraging to the tiny Christian minority here which often feels under pressure from the Muslim majority. They hope this visit may lead to a new spirit of openness and understanding.

ABERNETHY: Kim, the pope’s trip seems to have been a great success at the level of words and gestures. But what about the practical negotiations, for instance, with the Eastern Orthodox churches?

LAWTON: Certainly, this was an important symbolic event, to see the pope and the Eastern Orthodox patriarch arm-in-arm — very important symbolically. But, as you say, the practical issues are still a little uncertain. The role of the pope, as we mentioned, is really important and a big stumbling block. The Eastern Orthodox churches do not want to accept the pope as the ultimate authority of their Church in any way, and that’s an issue that doesn’t seem to have an easy solution. But, nonetheless, they did pledge to work together on issues they do agree on, things like the environment, human rights and certainly rights for religious minorities, which is a big issue here in Turkey.

ABERNETHY: And of course that same issue affects relations with Islam — all the Islamic countries. Again, the symbols have been positive. But there is this question about persuading Muslim countries to guarantee freedom for religious minorities.

LAWTON: That’s a big issue for Pope Benedict, and it is an issue that he brought up here, just the fact that he wants Christians here in Muslim countries to be able to worship freely, he says, as Muslims are free to worship in Christian nations. He brought that up here, and it was a message that was part of his broader message of peace and reconciliation. And it’s interesting to see whether because he came here but still held that message, if that will have an impact in the Muslim world. One Turkish leader here told me he thinks it might take a hawkish pope, in fact, to make peace, just like it was Nixon who opened up China.

ABERNETHY: And have you had a chance to get a sense of how successful the pope was with rank-and-file Muslims — I don’t know exactly what the phrase there would be, but the man in the street?

LAWTON: We’ve talked with a lot of Turkish people, and I think they were pleasantly surprised at how this visit went. They were pleasantly surprised at the tone of reconciliation that the pope struck. But behind it all there was an interesting concern, just to see the Roman Catholic pope and the Eastern Orthodox patriarch coming together. It’s hard to believe, but here in Turkey that’s seen as a potential threat — the fact that even though there are only about 2,000 Greek Orthodox Christians who live here, but this notion of Christianity symbolized by the pope and the Eastern Orthodox patriarch coming together and perhaps forming some kind of Christian empire that could in some way threaten not only Turkey but Islam — that’s something people talk about here, and that was certainly underlying a lot of this visit.

ABERNETHY: Any sense, Kim, of how that perception or that fear in the Muslim world could be alleviated?

LAWTON: Well, I think precisely with Benedict coming here and talking with religious leaders and political leaders here, the symbolism of him being in the Blue Mosque and, in fact, praying in the Blue Mosque — it was really interesting. There was a lot of speculation in the Turkish press about whether Benedict would pray in Aya Sofia, the church-turned-mosque-turned-museum, or whether he would make the sign of a cross, and that might be seen in some way as trying to reclaim that church. But he did not do that. However, when he went to the mosque he did a prayer with the grand mufti, and that was seen as a real sign of respect that will reverberate around the Muslim world.

ABERNETHY: Kim Lawton in Istanbul, many thanks.