Fair Use of Water

There’s a battle underway in the state of Nevada over the proper use of water. Las Vegas wants water so it can keep growing. But farmers and ranchers fear Las Vegas’s thirst will destroy their livelihood.

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: There's a battle underway in the state of Nevada that is as old as the settlement of the West. It's over water -- scarce water. Las Vegas wants water so it can keep growing. But farmers and ranchers fear Las Vegas's thirst will destroy their livelihood. Lucky Severson reports.

LUCKY SEVERSON: Looking for the good life, the American dream? Look no further. Just follow the shimmering water which is not far from the Eiffel Tower and the sparkling neon.

DANNY THOMPSON (Nevada AFL-CIO): People are coming here because there's jobs, and there's jobs that pay enough that you can live and have a house and have insurance and have a good life.

SEVERSON: Danny Thompson with the Nevada AFL-CIO says a new house is completed here every 23 minutes, and some of those high-rise casinos take 10,000 workers to build and 10,000 to operate. It's already the country's fastest growing metropolis, with a population of almost two million and projected to double in the next 20 years. And speaking of the American dream, there were more than 60 golf courses at last count.

And it is not just the city of Las Vegas and its suburbs. I'm standing about 60 miles northeast of Las Vegas, where construction is underway for a gigantic golf resort that will ultimately include 16 golf courses, 159,000 housing units, and take up approximately 67 square miles.

There is a downside, of course, to this explosive growth in dry southern Nevada. Where will the water come from?

Mr. THOMPSON: Well, you know, Mark Twain said whiskey's for drinking and water's for fighting over. So, water's a problem.

SEVERSON: Actually, it's a pretty large problem, made more urgent by a seven-year drought along the Colorado River that feeds Lake Meade. The lake's water level is only half of what it should be.

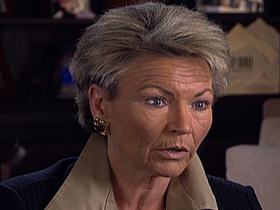

The solution, in the view of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, lies under the high desert basins. The city would spend at least $3 billion to pipe the water from underground aquifers some 250 miles north of Las Vegas -- enough to supply about 700,000 people. The head of the Water Authority, Pat Mulroy, says it's a good, solid plan.

PAT MULROY (Southern Nevada Water Authority): There would not be an American West were it not but for the ability to move water from one place to another. Without inner basin transfers, this state has no future.

SEVERSON: Once the future of the West was thought to be gold. Not anymore. The future is ultimately tied to who has the water. It's a red-hot issue of justice and fairness, and it won't be going away. That's the view of former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt.

BRUCE BABBITT (Former Secretary of the Interior): Las Vegas is handing out a death sentence to rural Nevada. It is basically a unilateral decision by Las Vegas that the growth will take place here.

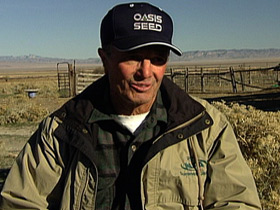

CECIL GARLAND (Rancher): I see it as a moral fight for the simple reason Las Vegas is a city of glitter, gluttony, gambling, and girls, and this valley is a valley of children, cattle, church, and country. You make the choice.

SEVERSON: Cecil Garland is an 80-year-old rancher in Snake Valley, and he's not about to give up his water if he can do anything about it. That's the big question. Bruce Babbitt says it will be an uphill battle.

Mr. BABBITT: Water in the West flows uphill to money, and Las Vegas is a classic example. They have the money and the resources to buy and transport the water.

Ms. MULROY: There is a modicum of truth to that. But I don't think that that's the way it should be in the future necessarily, and that's certainly not our objective. We are legitimately and sincerely seeking a partnership.

SEVERSON: Mulroy says Las Vegas wants to work with the ranchers to reach an agreement on the pipeline, but any decision seems a long way off, and the ranchers are suspicious.

DEAN BAKER (Rancher): I don't think this is a logical, reasonable answer for southern Nevada needs, nor do I think it's good for this environment or this valley.

SEVERSON: Dean Baker and his three sons own and operate this 12,000 acre ranch with about 3,000 head of cattle. Baker says as a farmer and an environmentalist he's concerned that the desert will become a barren wasteland, unable to sustain even the mule deer, let alone cattle.

Mr. BAKER: This is the worst crisis our family's faced in over 50 years here. I mean, it is going to have huge impacts, and it takes away the opportunity and future. When the water is gone, the future is gone.

SEVERSON: To show the effects of what even a small amount of pumping water can do on this arid land, Baker points out a spot that was once a wetland before he pumped the ground water to use on his ranch.

Mr. BAKER: Our small amount of pumping in this valley has dried up springs, wells like this. They're a drop in the bucket compared to what southern Nevada wants to do. We know what it does when you start pumping.

Mr. BABBITT: We went through this at the turn of the century in the growth of Los Angeles, when Los Angeles reached out to the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada to a place called Owens Valley and stripped all of the water, and if you go to the Sierra Nevada, to this day you will find a lot of bitter memories.

SEVERSON: It's not only local ranchers and farmers who are worried. Rangers with the Lehman Caves in the Great Basin National Park are concerned that if the water table dries up, it will harm the stalactites and stalagmites that are so dependent on water for their formation. There's concern as well for several spring-fed creeks in the park.

Ms. MULROY: We will mange those basins in such a way that there is no environmental impact.

SEVERSON: The ultimate impact on the environment and the ranches when the water is piped from the aquifers is unknown, according to Susan Lynn, a regional water expert.

SUSAN LYNN (Great Basin Water Network): No, I don't think they know that, because they say their models are in-operational. They're not using them.

Ms. MULROY: As we stress these basins and we see what, if any, impacts there are, we will move pumping, cease pumping in certain areas.

Mr. GARLAND: You've got an 84-inch pipeline that you've got to try and keep full of water. If you've got all those people on the south end of that pipeline that's depending on turning that faucet over and getting water and flushing their toilet and so forth and so on, do you mean to tell me that there is a force that we know of or can conceive of that is going to turn those pumps off here and shut those people off down there?

SEVERSON: Garland and others say piping water to Vegas is only a stop-gap measure, not a permanent solution. But Pat Mulroy says the extra water, along with the city's stringent water conservation measures, will go a long way. The city has invested considerable effort in conservation. Many lawns have been replaced with so-called "water-smart" landscapes. Homeowners are paid a dollar per square foot for grass removed.

Ms. MULROY: One of the biggest struggles we've had in our effort to create a conservation ethic in this community is to create the real Las Vegas that is away from the virtual reality that you find on the Las Vegas strip.

SEVERSON: The big users are not the giant casinos. They recycle. The entire strip uses only three percent of the Las Vegas total. Golf courses use tremendous amounts of water, and there are still some spectacular examples of consumption, such as this development called The Lakes at Las Vegas, which opened several years ago.

Ms. LYNN: The Lakes at Las Vegas use one percent of Las Vegas's total water supply. It just evaporates into the air, and that to me is a tremendous waste of fresh water.

SEVERSON: One of the strongest ethical arguments in favor of piping water to Vegas is that it will benefit and give jobs to hundreds of thousands of people, as compared to a few dozen ranchers and a few thousand residents around Baker, Nevada.

Mr. BAKER: We produce a lot of food, a couple million pounds of beef every year. We produce a lot of hay that goes to dairies in California that produces milk, and I don't know the value, but I think we are both preserving and enhancing the environment and being -- using it to be productive in a productive way.

Mr. GARLAND: I can afford somehow or another to keep up the struggle because my daughter, my grandchildren, the future of my ranch, the beauty of where I live, the quality of life I have is all put up in jeopardy.

SEVERSON: If history is any guide, the aquifer water in the valley where Cecil Garland and Dean Baker raise their cattle will end up in a pipe on its way to Las Vegas. The unknown is whether there will be enough left over to make a living.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I'm Lucky Severson in Snake Valley, Nevada.

ABERNETHY: Western water rights are famously complex, but in the end the decision on whether Las Vegas can get that high desert water will be made by the state engineer.

There’s a battle underway in the state of Nevada over the proper use of water. Las Vegas wants water so it can keep growing. But farmers and ranchers fear Las Vegas’s thirst will destroy their livelihood.