In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Prayers and Portraits

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, a new exhibit in Washington of a special kind of Renaissance religious paintings. They’re called diptychs — two panels hinged. Our guide is John Hand, curator of northern European Renaissance painting at the National Gallery of Art.

JOHN HAND (Curator, Northern Renaissance Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC): The exhibition “Prayers and Portraits: Unfolding the Netherlandish Diptych” consists of religious paintings produced under the umbrella of the Roman Church and spans the 15th and 16th centuries.

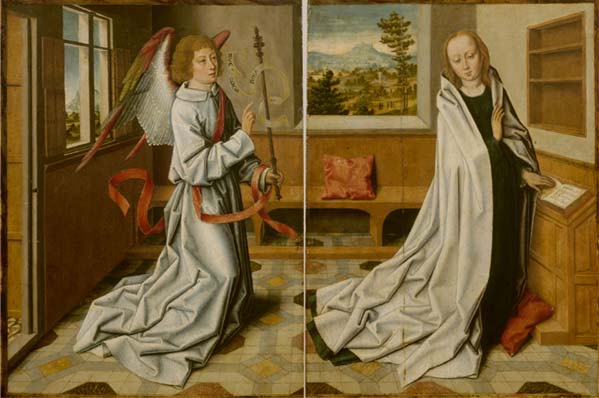

A diptych consists of two panels of the same size that are framed and hinged so they can be opened and closed like a book. They could have been used for traveling, or they could have been simply put away at a desk or drawer, taken out when needed.

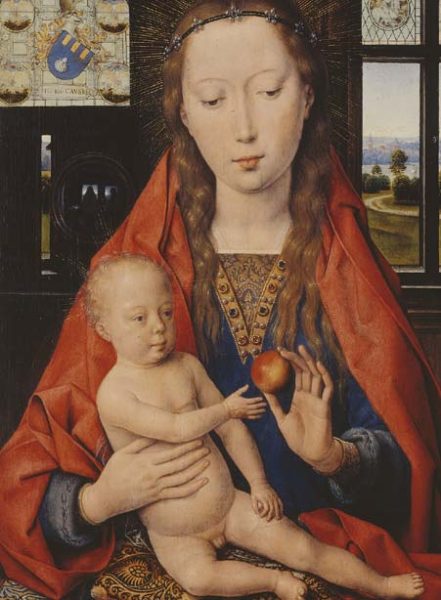

The devotional portrait diptych contains an image of the Virgin [and] Child on one wing, usually on the left, and then an image of the donor, who is shown with an attitude of prayer and adoration on the right wing, praying to the Virgin. In general, these diptychs were aids to devotion and meditation and contemplation.

For many of these devotional diptychs, the Virgin is larger than the donor. There’s a kind of circularity of vision. The donor looks to the Virgin, the Virgin looks down at the Child, and then the Child looks across to, back at the donors. Since diptychs often involve private contemplation and meditation, they were very popular with various orders in the 15th and 16th century, so in the exhibition you will find Cistercian monks. There are also Franciscans. We also have a wonderful diptych which depicts Willem Bibaut, the head of the Carthusian monastery in Grenoble.

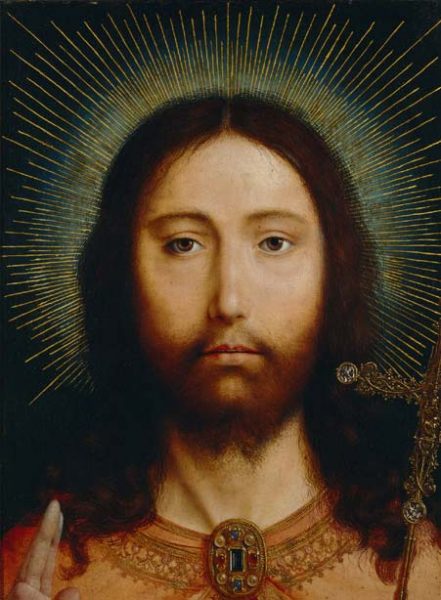

It’s important to realize that saints played a pivotal role in people’s lives, and so this diptych depicts two saints, John the Baptist and Veronica, and Veronica is holding the sudarium or the veil which contains the miraculous image of the face of Christ. This is a figure that you pray to for protection against illness, sickness, death. And the figure of John the Baptist is equally important. His job, as you see here, is to proclaim Christ as Messiah, as the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world.

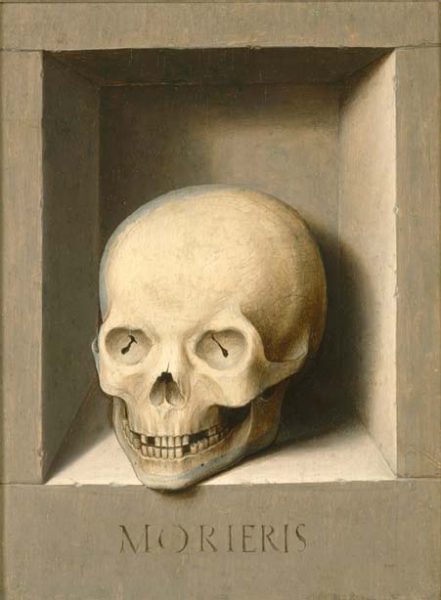

On the reverse of the John the Baptist is a skull, a human skull in a niche and the word in Latin, Morieris, which means “you will die.” So that it refers to the inevitability of death. The image on the back of the St. Veronica also has to do with the triumph over death. It is the chalice of John the Evangelist.

So together all of these images are extremely powerful and protective of whomever owned it.