In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Holocaust Remembrance Exhibit

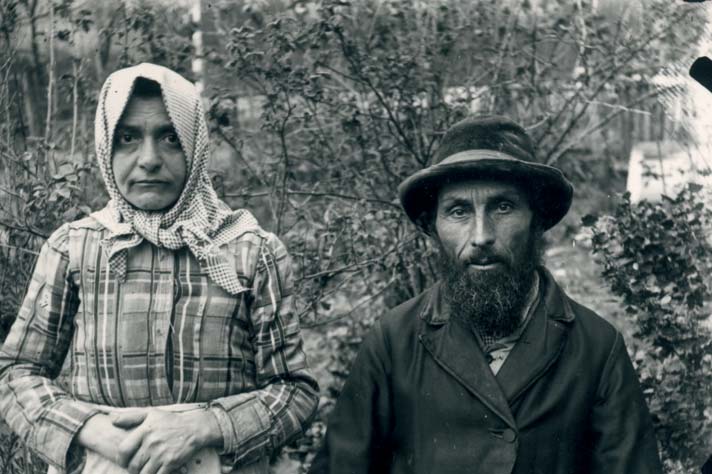

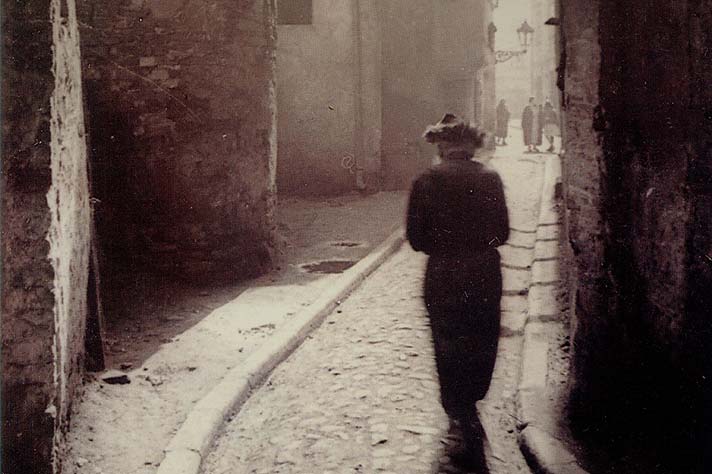

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: This Sunday (April 15) is Holocaust Remembrance Day, and we remember with a visit to a powerful exhibition at New York’s Yeshiva University Museum. The exhibit is called “And I Still See Their Faces,” and it’s made up primarily of family photographs of members of pre-war Poland’s once thriving Jewish community. Before the Holocaust there were 3.2 million Jews in Poland, the largest Jewish population in Europe. By the end of World War II and the Holocaust, more than three million Polish Jews had been killed, among them most of those remembered in these images. Kim Lawton tells the story.

KIM LAWTON: The exhibit was the dream of Polish-Jewish actress Golda Tencer. Tencer created the Shalom Foundation in Warsaw to preserve the once thriving Jewish life and culture in Poland. In 1994, she sent out an appeal on Polish media for people to send in photographs and memorabilia of Jewish families prior to the war.

Her friend, Rivka Ostaszewski, a child of Holocaust survivors, explains what happened next.

RIVKA OSTASZEWSKI: And people were laughing at her and saying, “Come on, I mean, it’s so many years after the war. Nothing will be there.” Well, surprisingly enough, there are over 9,000 photos and items sent into the Shalom Foundation, most of them sent by Poles who were neighbors or friends or just people that found something and held onto it, hoping that somebody would come back.

LAWTON: These photos were not taken by professionals. They were from family albums found in attics and basements — some even hidden in walls. They provide a diverse glimpse of everyday Jewish life in Poland, from the urban cities of Warsaw, Lodz, and Krakow to the rural life of the villages or shtetls.

They show many families, some of those celebrating Jewish holidays or enjoying a beach vacation. There are photos of Orthodox rabbis and boys learning in a yeshiva. And there are many touching images of children.

A 14-year-old girl in Auschwitz saved this tiny photograph of her mother.

The exhibition also has personal ties for Rivka — a photo of her parents who escaped to Russia. Before they left, Rivka’s mother pleaded with her father to join them.

Ms. OSTASZEWSKI: And my grandfather said, “No, I am not going. Don’t worry, daughter. You know, I lived through the first war, and I actually did business with the Germans. We’ll survive this one, too.” I mean, they had no idea.

LAWTON: Rivka’s entire family on her mother’s side died during the war.

Ms. OSTASZEWSKI: We don’t know if they were sent to Auschwitz or Treblinka or how they actually, you know, perished. We don’t know. And the family was huge. My mom used to say that she had 10 brothers and sisters, and the oldest one already had 10 of her own children.

LAWTON: This picture of Rivka’s uncle and friends on a picnic in Warsaw is the only memory that remains of her mother’s family.

Ms. OSTASZEWSKI: This is their memorial. The exhibit and the album, for me, and I suppose many people here, represents the memorial of those people, because there is not a grave that we can go to. There is nothing else left of that family that we know of.

LAWTON: Members of the Shalom Foundation believe this exhibit is important not only as a memorial to those lost but as a legacy to celebrate the Jewish life and culture that once existed, and to educate future generations.

Ms. OSTASZEWSKI: Most and foremost is to remember — to remember and never let it be forgotten and never let it happen again.

ABERNETHY: It’s estimated that compared to the more than 3 million Jews in Poland before the Holocaust, there are now fewer than 10,000 living there.