In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

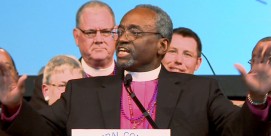

INTERVIEW Bishop John Chane

Read more of the R & E interview with Bishop John Chane of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington:

Q: How important a moment is this for the Episcopal Church and the worldwide Anglican Communion?

A: Well, from the perspective of the Episcopal Church it’s a very important time in our life to be very clear about who we are, you know, where we’ve been, and where we’re going to be going as a collective church. For the larger Communion, I think it’s a time to really reclaim what I think is the great activity and work of the church globally, and that is to say we have far more important things to do than to fight over these issues of human sexuality that we cannot resolve at this time and be engaged in the mission of the church, given the situation that is very much a part of the definition of the Global South.

A: Well, from the perspective of the Episcopal Church it’s a very important time in our life to be very clear about who we are, you know, where we’ve been, and where we’re going to be going as a collective church. For the larger Communion, I think it’s a time to really reclaim what I think is the great activity and work of the church globally, and that is to say we have far more important things to do than to fight over these issues of human sexuality that we cannot resolve at this time and be engaged in the mission of the church, given the situation that is very much a part of the definition of the Global South.

Q: The bishops are going to be asked again to respond to the communiqué that was issued in Tanzania. What is your sense about where the bishops are heading on that?

A: We received that communiqué with a great deal of respect, but the House of Bishops has already spoken, and the other thing that primates need to understand, and I think other people even in our own church need to understand, is that the bishops, really, we can create “mind of the house” resolutions. We cannot change the direction or, in fact, speak to that kind of question as a defining moment in the life of our journey as Episcopalians. That’s up to the Executive Council, and so both the House of Bishops and the Executive Council have made it very clear that the scheme offered by the primates in Dar es Salaam was a scheme that we could not incorporate or accept.

Q: Remind people how the Anglican Communion works. The rest of the world cannot tell the U.S. church what to do, can it? The U.S. church is autonomous.

A: I don’t think autonomy is the right word. We’re a collection of very, very different provinces that in a sense are self-governed but in fact are connected to each other by the office and position of the Archbishop of Canterbury. We’re in communion with one another through our communion with the archbishop. And so even the discussions that have ranged for years about people not being in communion with the Episcopal Church — it’s really inaccurate. You are in communion with us unless the Archbishop of Canterbury says you are not. So I think the issue here in terms of where we are right now is that our church is very much a post-colonial church. It’s a bicameral legislative church, and a lot of folks don’t understand that in terms of the balance of powers, the check and balances systems that are retained within it.

Q: Because of that is there a growing frustration in the U.S. with strong international pressure?

A: Well, I think we have to get to the root of what the issues are here. For me, as one bishop, the issue is who’s going to control the Communion. Who’s in charge? Who has the power, which is an unusual place to be in, given the loose confederation of churches and provinces that make up the Anglican Communion. I look at it less as a serious threat to the American church and more as an extremely serious threat to the concept and the life of the Anglican Communion. That, to me, is far more serious, and that’s an issue that we don’t really talk too much about, other than the fact that there could be dissention and maybe a dissolution of some provinces away from the Communion after [the 2008] Lambeth [Conference] or maybe even before Lambeth.

Q: How do you balance the U.S. church’s moving ahead with what it feels called to do, based on its canons and its reading of scripture on one hand, and the concerns of the rest of the Communion on the other?

A: We are part of the Communion. We will be a part of the Communion until the Archbishop of Canterbury says we are not a part of the Communion. We’re absolutely committed to being in the Communion. We believe that the Anglican Communion is probably one of the greatest hopes, at least for what I would call the broad Protestant denominations in the world today in terms of addressing global issues, and also our own domestic issues. Without the Communion, we become extremely weak. We become independent dioceses, independent provinces. We don’t have resources, and we don’t have the skill sets that are needed to address what’s going on domestically and globally.

Q: Some in the gay and lesbian community are concerned that, in an attempt to appease or to meet the concerns coming from other parts of the Communion, the Episcopal Church will back away from their issues. How important is staying in the Communion versus dealing with these divisive issues?

A: From my point of view, the Episcopal Church has been very clear about its support and its care for members of the gay and lesbian communities that have been a part of our life for forever. Legislation crafted at General Convention makes that very clear. The statement that was issued by the House of Bishops to the primates who had sent us the scheme from Dar es Salaam was very clear, you know. We are not going back to Egypt, and I think the gay and lesbian community, if they don’t understand that, they need to understand that. I think our African partners, for the most part, the reasonable partners who clearly may disagree with us but look at a much bigger picture of what it means to be in Communion, understand that as well. They also understand that they’re beginning to address those very complex human sexuality issues in their own countries and in their own provinces. And so what we do may not necessarily be a lead in or a support for them, but it does say it is a very problematic piece. In terms of what’s going to happen in New Orleans, I really don’t know. I do know that the House of Bishops is very much united in terms of what it will and will not do, what it can and cannot do by constitution and canon. I also believe that we will have to exhibit some sensitivity to what we would call, what others have called “the Windsor bishops.” I mean, they have some very real concerns, and the people that they serve — these bishops have some very real concerns in terms of serving people in the dioceses that they’ve been elected to care for. We’ve got to find a way in which to provide them with appropriate care and support, and respect those positions as much as we hope they would respect ours. But we are not going back to Egypt.

Q: People have been searching for a way to accommodate both those positions for a long time. Is it still possible to find that accommodation?

A: I think it’s very possible. I think it’s unfair to label me as anything other than a bishop in the Episcopal Church, but I’ve been labeled a lot of things. … But I would say this, that some of my closest friends in the House of Bishops are bishops who are on the other side of the aisle, who are very conservative, and some who are “Windsor bishops,” and we look at the church in some ways from a very different perspective, and yet we understand that the strength of our common mission is the greater gift, rather than the evil of being divided. And so if there are some of us who can be in that position within the American church, and we can carry that through New Orleans, there’s no reason why that cannot be the reality in the rest of the Communion. But what it takes is you’ve got to — you can’t write letters, you can’t send e-mails, you can’t send press releases out. What you have to do is you have to sit down at a table, you have to look each other in the eye, and you have to let it go, and you’ve got to be consistent and hardworking at dialogue and also in listening, and dialogue and listening are issues and pieces of life in the Episcopal Church [that] have been, in the past, pretty much lost entities, and I think we are reclaiming that, given the challenges that are before us both domestically and globally.

Q: There has been a trend of disaffected U.S. priests being made bishops here for other parts of the Anglican Communion, for Africa. What is your reaction to that?

A: It’s very painful, you know, and one of the things that I expressed [at a church meeting] this summer in Spain was they need to understand how painful that is in the life of my province, my church, the Episcopal Church, and how much it undermines the very concept of what it means to be an Anglican or to be a part of the Anglican Communion. What’s it going to do? I think very little. I think there’s so much division right now within what used to be considered the right wing of the Episcopal Church, in terms of who’s in control and who has the power, who’s going to make the decisions, that all of these consecrations and all of this divisiveness in 10 or 15 years will be something that you and I are going to look back upon, God willing, and we’re going to see it as one of those significant painful blips in the growth and life, I think, of a great Communion.

Q: What do you hope to hear from the Archbishop of Canterbury? What message do you hope he brings?

A: Well, first of all, I hope he listens and hears how much we respect the office. I hope he hears how faithful we are and committed we are to the Communion. I hope he also learns something about the life of this church, which I think he has not heard clearly, and that is that what he might perceive as a division in this church — I mean, I’ve heard figures of 40 percent or more people who are disaffected with the way in which the Episcopal Church is moving, you know. That’s fallacious. It’s absolutely not true. What is he going to come away with from this meeting? I hope that what he comes away with, along with having an opportunity to hear us and be a part of our community’s life, I hope he comes away understanding that, you know, we are not as divided as some would say we are, and at the same time we are willing to live into those pieces of legislation that we passed at the General Convention in Columbus, Ohio, recognizing that maybe the language in those resolutions might not be as clear as he would like. Nonetheless, the bishops in the House and I know others in this church respect that legislation and will live into it well. You know, I think we’re in great shape. I’ve had, in the last probably 8 or 9 months, I think I’ve been more hopeful about the future of this church and it’s growth than at any time since I’ve been ordained, and that means growth in the Communion. It means growth in the Episcopal Church.

![]()