Eric O. Hanson: A Religious-Political Pilgrimage to the UN

Today Pope Benedict XVI, like his predecessors Paul VI and John Paul II (twice), made a religious-political pilgrimage to the United Nations. The Catholic Church, which suffered greatly from both Catholic and Protestant nationalisms of the Westphalian system of sovereign nation states (1648-1918), remains anchored in the global system both institutionally and theologically. Indeed, support for the United Nations has endured as a central tenet of Vatican foreign policy and Catholic social theory throughout the postwar period. This support, as Benedict said, is rooted in “the unity of the human family” and in “the innate dignity of every man and woman.”

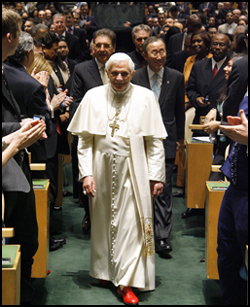

UN Photo/Mark Garten |

The pope reprised John Paul II’s call for a “great degree of international ordering,” respecting, of course, the principle of subsidiarity, which calls for action at the lowest effective level. Benedict stated “it is necessary to recognize the higher role played by rules and structures that are intrinsically ordered to promote the common good, and therefore to safeguard human freedom.” The pope emphasized that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights found its basis not just in positive law, but “by the common desire to place the human person at the heart of institutions, laws and the working of society”. Therefore “human rights are increasingly being presented as the common language and the ethical substratum of international relations.”

Most religious thought, including this speech, emphasizes that rights also call for responsibilities. Interreligious dialogue must bring together all people of good will to solve global problems like war, poverty, and environmental degradation. Benedict especially mentioned “those countries of Africa and other parts of the world which remain on the margins of authentic integral development, and are therefore at risk of experiencing only the negative effects of globalization.” Theologically the pope tied the UN’s “responsibility to protect” to previous writings of the sixteenth-century friar-scholar Francisco de Vitoria and strong support for universal human rights to the fifth-century bishop Augustine. The pope also emphasized the crucial importance of religious freedom among human rights.

What role, then, can the pope and other religious leaders like the Dalai Lama and Jewish and Islamic scholars play in “the new world disorder” of the twenty-first century? We have all left the “security” of the Cold War paradigm for an increasingly fragmented, chaotic, and polarized world at all levels, from the very local to the most global. The rise of countries like China, India, and Brazil and the communications revolution mean that many more nationalisms will have to be factored into any common decisions. In fact, any global problem worth solving, from Darfur to Palestine to global warming, will require the cooperative efforts of all the stakeholders. A single stakeholder, even by inaction, will be able to block most solutions, whether it be Beijing on Darfur or Hamas on Palestine. We have thus entered an era where the only successful global politics will depend on overwhelming cooperative “grand majorities” among nation states and political movements with a multitude of reasons to distrust each other.

What might religion in general and Catholicism in particular contribute to building trust among such disparate international political actors? The significances of interreligious dialogue and cross-national understandings, especially between the global north and the global south, are obvious. The former demands men and women of considerable spiritual depth and shrewd political craft (“discernment” in the pope’s speech). The latter calls for men and women of every nation to orient themselves to the universal human common good and not to narrow nationalist agendas.

The principal importance of today’s papal speech to the United Nations is to call all people of good will to answer this challenge in hope. While secularism might have been the better political course for the West following the Thirty Years War, today’s incredibly complicated global society can only escape its increasing economic stratification, multiplying civil conflicts, and environmental degradation with increased motivation and participation of all believers.

— Eric O. Hanson is the Donohoe Professor of Political Science at Santa Clara University and author of RELIGION AND POLITICS IN THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM TODAY (Cambridge, 2006).