In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

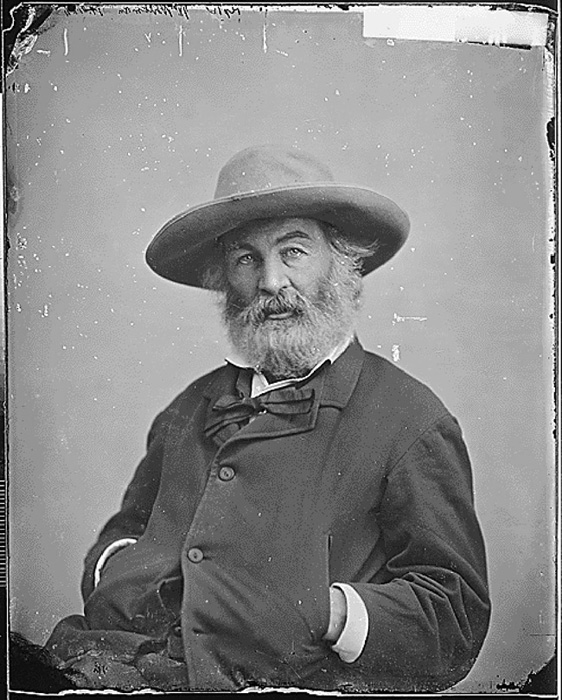

Worshipping Walt

BOOK REVIEW

Poet as Prophet: The Religious Whitman and His Disciples

by David E. Anderson

The link between religion and poetry has largely been lost to the popular mind in the Western world, especially in the United States. Even the minority of Americans who regularly read volumes of poetry rarely treat them as sacred texts or scripture, and poetry for the most part is not read as a guide to living, as many read the Bible, the Qur’an, or the Bhagavad Gita.

Of course, many poets today write on sacred themes, take up religious issues, and have recourse to the language and motifs of the transcendent and the numinous. There are any number of anthologies and collections that demonstrate the religious concerns of poets over time, such as the Library of America’s American Religious Poems, edited by Harold Bloom, or the slim but interesting Poetry of Piety, an annotated anthology of 28 Christian poems analyzed by New Testament professor Ben Witherington III and English professor Christopher Mead Armitage, or A Sacrifice of Praise, an immense 800-page collection of Christian poetry spanning thirteen centuries, edited by James Trott. Sometimes a single poet will organize a volume around a religious motif, such as Wendell Berry’s Sabbaths, or Geoffrey Hill’s The Triumph of Love, or sequences such as T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets and John Berryman’s series “Eleven Addresses to the Lord” in his Love & Fame.

None of this poetry, however, is received or read as scripture, nor are the poets acclaimed as prophets and religious teachers or revered as Christ-figures.

Such was not always the case.

Before the twentieth century there was a long tradition of the poet as prophet and seer, and poetry as a form of religious language. The Hebrew Bible is replete with poetry, not only in the songs that make up the Book of Psalms but also in the inspired utterances of prophets such as Isaiah and Jeremiah. As Michael Robertson, a professor of English at the College of New Jersey, points out in Worshipping Walt (Princeton University Press, 2008), his recent study of Walt Whitman and his disciples, “the idea of the poet-prophet remains alive in non-Western cultures such as India, where ‘poet-saints’ like Kabir are revered, and Vietnam, where the Cao Dai sect regards Victor Hugo as a prophet.” As recently as 150 years, Robertson adds, many Americans and Britons were similarly prepared to accept the creative writer as a divinely inspired figure. He cites William Blake (1757-1827) as the first modern artist to be widely regarded as a poet-prophet, and many readers saw in Walt Whitman Blake’s natural successor as religious seer.

Whitman’s career, from his early writing apprenticeship as journalist, printer, and teacher in the 1830s and 1840s through the succeeding editions of Leaves of Grass, beginning in 1855, was a time of religious and intellectual ferment and political turmoil in America. Developments in science were undermining settled Christian orthodoxies, the anti-slavery movement was giving rise to debates over the meaning of democracy, and new religious movements, such as Mormonism, Spiritualism, and Theosophy were changing the spiritual landscape of antebellum America.

David Kuebrich, in his groundbreaking study recovering the religious dimension of Whitman’s work, Minor Prophecy: Walt Whitman’s New American Religion (Indiana University Press, 1990), notes three elements in Whitman’s contemporary culture that are important for understanding the poet’s spirituality and the religious vision at the heart of Leaves of Grass: the Romantic religious worldview, including but not limited to American Transcendentalism; the new discoveries in evolutionary thought in geology, astronomy, and biology; and the doctrines of perfectionism and millennialism that pervaded mid-century Protestant thinking. Whitman was familiar with and influenced by everything from the nascent Sunday school movement to the revivals of Charles Finney, as well as the popular phrenology phenomenon. But it is important to understand that Whitman appropriated elements of these currents not within a personal Christian theology or spirituality, but in a far more generalized sense. They were background elements for his own post-Christian religion.

Whitman’s self-understanding as a prophet and founder of a new American religion was already being developed when he came upon Ralph Waldo Emerson, but Emerson’s definition of the poet as a religious prophet, as well as his private praise for the first edition of Leaves, which Whitman nevertheless made sure was widely known, gave Whitman the encouragement needed to pursue his vocation. One can sense the unconscious link between the two in an Emerson journal entry in 1836, where he declares, “Make your own Bible,’’ and in Whitman’s 1857 notebook entry: “Leaves of Grass – Bible of the New Religion.”

“The 1860 Leaves of Grass is particularly insistent upon Whitman’s religious intentions,” Robertson writes, “but his interest in writing a new American bible is evident in every version of Leaves of Grass from the 1855 first edition on.”

Whitman believed himself a prophet and regarded Leaves as scripture, as did many of his readers. While he hoped his poetry would find its readers among the mass of working and laboring classes, his most admiring acolytes came from the middle and upper-middle class of literate readers. Robertson chooses nine of the most ardent and articulate, who wrote on Whitman both privately and publicly and left behind a body of work that is invaluable for understanding the religious and spiritual impact of Leaves of Grass over the first 75 years of its reception.

For each of the disciples Robertson studies, the encounter with Leaves of Grass was a profound and life-altering experience. In this they are typical of one another, but they also represent responses to different aspects of the poem – its understanding of nature, its celebration of sexuality, its advocacy of a radical equality and democracy. At the same time, there was a strong desire for each of them to be in the poet’s presence and to draw spiritual sustenance from him. One of them, Anne Gilchrist, read Leaves in such personal terms she packed up her household in England and moved to the United States, at first expecting to marry Whitman but ultimately forging a deep friendship and discipleship that lasted through her ultimate return to England. There she continued to champion the poet and his work. All of them, however, spent a great deal of time in Whitman’s company, and his charismatic personality seemed to work the same kind of influence on them as other religious leaders have had on their followers.

Some of the true believers Robertson focuses on, such as John Burroughs, Horace Traubel, and the English trio of Oscar Wilde, Edward Carpenter, and John Addington Symonds, continue to be known and studied in American and British academic circles, Others, such as William O’Connor, R.M. Bucke, and J.W. Wallace, as well as Gilchrist, while significant in their own right, have generally faded into contemporary obscurity.

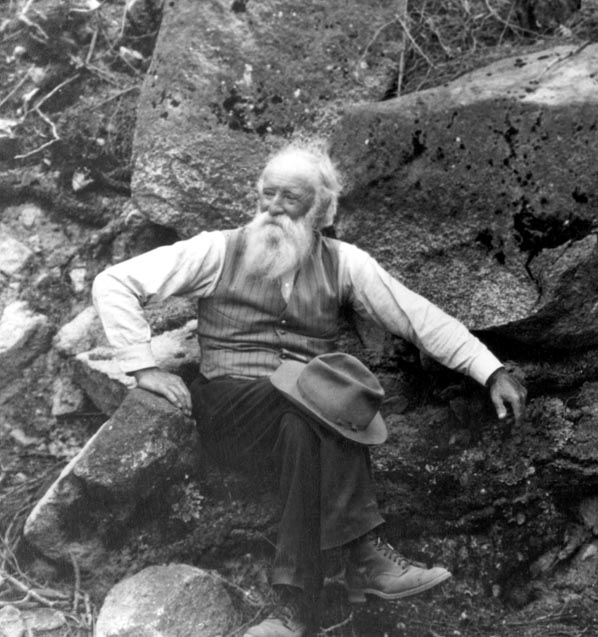

All of the disciples drew from the language of Christianity, the primary religious speech available, to express their fervent feelings about Whitman and the evolving poem that is Leaves of Grass. O’Connor was the first but not the only one to compare Whitman to Jesus, while Burroughs, one of the most influential nature writers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, more famous than either Henry David Thoreau or John Muir, found in Leaves “primarily a gospel and … only secondarily a poem.” That, too, was a view shared by all the followers. In Robertson’s view, Burroughs “pioneered the spiritualized interpretation of Leaves of Grass that was furthered by subsequent disciples” and that persisted into the 1920s, when a more secular reading of Whitman – and other texts – moved to the forefront of academic studies.

Gilchrist, a popular science writer, widowed mother of four, and friend of the Rossetti family – Christina, Daniel Gabriel, and Michael – was introduced to Leaves in 1869, fourteen years after the publication of the first edition. She quickly embraced Whitman’s complex celebration of women’s sexual and spiritual equality coupled with praise for motherhood. Robertson argues that Gilchrist, like many Victorian religious progressives, believed that institutionalized Christianity had distorted Christ’s life and that Whitman, as a new Christ, was to bring to humanity a new faith to replace those beliefs shattered by the discoveries of modern science.

Robertson’s trio of British writers – Symonds, Carpenter, and Wilde – were literati attracted to Whitman because of what seemed to them his sanctification of guiltless love between men as well as a religious vision of the ecstatic apprehension of the divine. Of the three, Carpenter – famous in his time for representing a combination of avant-garde poetry, mystical religion, and radical politics aimed at a host of social reforms – was most influenced by Whitman, and in 1874 he would write to a friend a few days after meeting the poet in Camden, New Jersey, “The likeness to Christ is quite marked.” Gilchrist, too, thought Whitman resembled Jesus.

There were efforts by some of the disciples, most notably Horace Traubel, to institutionalize their Whitmanite religion despite the poet’s dismissal of any such efforts in Leaves: “I charge that there be no theory or school founded out of me, / I charge you to leave all free, as I have left all free.” But two months after Whitman’s death, Traubel formed the Walt Whitman Reunion and together with others founded the Walt Whitman Fellowship. Its last meeting was in 1919 at the centennial celebration of Whitman’s birth.

As the original generation of disciples who had been spiritually nourished by both the poetry and the presence of Whitman died off, they were replaced by readers and critics who saw Whitman as a poet – a great one, perhaps – but not as a mighty spiritual force or a prophet with a sacred purpose. Still, as Robertson writes, “the tribe of Walt” was from the beginning intent on rescuing Whitman from obscurity on the one hand and, on the other, from charges of incoherence and obscenity. “Thanks in great part to their efforts,” he concludes, “Whitman’s fame spread rapidly so that, by the time of his death in 1892, he was perhaps the most widely known U. S. poet in both North America and Great Britain.”

Despite the lack of any religious institutionalization of Whitman’s gospel, Robertson finds plenty of anecdotal evidence in contemporary America that Whitman continues to serve as a spiritual guide and that Leave of Grass is often a touchstone in many people’s eclectic spiritual seeking. There is, for example, LeavesofGrass.org, a Web site run by gay rights activist and Quaker Mitchell Gould. A self-described “public historian,” Gould traces Whitman’s links to sailors, gays, and Quakers as the foundation for a provocative reading of the spirituality of Leaves of Grass. Neil Richardson, a community organizer Robertson found in Washington, DC, doesn’t believe Whitman was gay, and though he is not himself a Quaker, he has led sessions he calls a “Walt Whitman Meditation,” based on passages from Whitman’s notebooks and Leaves, at the historic Friends meetinghouse near Dupont Circle. Far from cosmopolitan Washington, Robertson also discovered an annual May 31 birthday celebration of Whitman in Conroe, Texas, where a dozen or so people gather “not for aesthetic pleasure – or not only for that – but for the chance to testify to this poetry’s meaning in their own lives.”

Indeed, it is a singular accomplishment of Robertson’s unusual but compelling study, blending the academic and the personal, that not only does it recover for this century the life-altering impact of Whitman’s poetry on a fascinating group of his first generation of readers, but it also reminds readers of all poetry – not just Whitman’s – that more can be at stake in the reception of a poem than intellectual satisfaction.

David E. Anderson, senior editor for Religion News Service, has written for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on many writers, including John Donne, Bob Dylan, Shakespeare, Marilynne Robinson, and Alice McDermott.