In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Beyond Tolerance: Searching for Interfaith Understanding in America

Book Excerpt

by Gustav Niebuhr

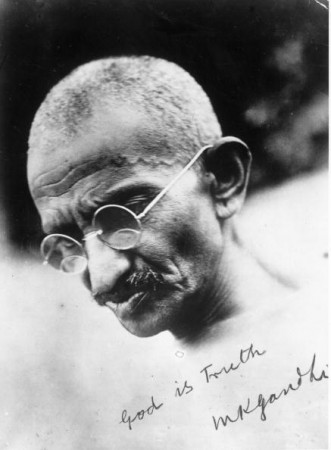

Gandhi is the gold standard when it comes to talking about interreligious respect. On the night that India became independent from Britain, the goal for which he had worked so hard, Gandhi avoided the ceremonies in Delhi and stayed in Calcutta with members of India’s Muslim minority. He had wrestled much of his life with the question of how to relate to a plurality of faiths. In his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, he told of growing up with almost daily experience of encounters that defied caste and faith boundaries, as a result of his father’s openness to speaking with people across Hinduism’s internal lines as well as with those of other religions.The senior Gandhi served as a minister to one of India’s princes. Jain monks visited the family, accepted gifts of food, and had friendly discussions with Gandhi’s father. The elder Gandhi also had Muslim and Zoroastrian friends who, the son reported, would talk to him about their religions, to which he listened with respect. Gandhi at first felt, he said, tolerant of other faiths. But later in life, he found that insufficient as a basis for dealing with non-Hindus. Instead, he adopted a position he described as respecting all religions as equals. He described the world’s major religions as being like branches of a tree, in which the trunk contained a dedication to truth and nonviolence. “Tolerance may imply a gratuitous assumption of the inferiority of other faiths to one’s own,” he wrote, “and respect suggests a sense of patronizing, whereas ahimsa”—that is, nonviolence—“teaches us to entertain the same respect for the religious faiths of others as we accord to our own, thus admitting the imperfection to the latter.”