In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Gerard Manley Hopkins

BOOK REVIEW

The Grandeur of God and the Life of a Poet

by David E. Anderson

Father Hopkins said the only true literary critic is Christ.

— John Berryman, “Eleven Addresses to the Lord”

“If I had not discovered Hopkins, I would have had to invent him,” poet and biographer Paul Mariani wrote in “Hopkins as Lifeline,” an essay recalling his first encounter as a college student in 1962 with nineteenth-century poet and Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins. It has been a long and fruitful relationship, including a doctoral thesis Mariani revised and published as A COMMENTARY ON THE COMPLETE POEMS OF GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS (Cornell University Press, 1970), more than a dozen scholarly articles, essays, and reviews, and now his full-length biography, GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS: A LIFE (Viking, 2008). It is a fine contribution to Hopkins scholarship, an often illuminating but sometimes uneven look at the Christ-haunted Victorian poet whose work, although never published in his lifetime, came into its own in the second half of the twentieth century, exerted a major influence on such poets as Elizabeth Bishop and John Berryman, and continues to influence young poets and attract the scrutiny of academics.

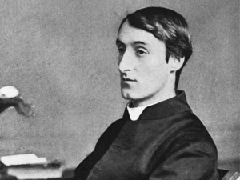

Gerard Manley Hopkins |

Mariani begins his biography with Hopkins’s most famous and indelible line, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God,’’ and he hangs on that line, composed in Wales in 1877 while Hopkins was working his way through the rigorous process of becoming a Jesuit priest, much of the contours of Hopkins’s life. “He believed it from his undergraduate years at Oxford as an Anglican seeker,’’ Mariani writes. “Believed it so strongly that it led in large part to his conversion to the Roman Catholic Church. Believed it as a Jesuit, and called on both Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises and the insights of the philosopher Duns Scotus into Christ’s Incarnation to formulate a theodicy and a poetics which would articulate and sing what his whole self—head and heart—felt.”

That is the strength but also one of the weaknesses of Mariani’s portrait. He is brilliant at explicating Hopkins’s poetry and many of the religious and theological impulses that give the poetry its force and meaning, and his mining of the journals and letters provides the data for Hopkins’s difficult relationship with the priesthood. But Hopkins the person is often missing.

Gerard Manley Hopkins was born on July 28, 1844, the eldest of nine children of a prosperous middle- to upper-middle-class family. He went to a very good grammar school, Highgate, where he excelled academically and in 1863 won a scholarship to Balliol, one of the best colleges at Oxford.

It is at Oxford in 1863—when Hopkins was 22 and caught up in contentious religious controversies that swirled through the school, particularly reconsiderations of the Church of England’s relationship with the Roman Catholic Church—that Mariani begins his narrative. Apparently a deeply pious but religiously conflicted young man, Hopkins was, as Mariani tells it, on the edge of the epiphany that “for complex reasons” he needed to become a Roman Catholic and a Jesuit priest. “So give it a day, a date, a going forth, a crossing over, all in an instant, finally, a yes and a yes again.…Call it what he would with its wondrous, irresistible forces working on him. The instress of it, like the ooze of virgin oil crushed in the press of God’s hands, an anointing, a yielding, a yes.” Instress, of course, is one of Hopkins’s coined words with a less than static meaning, but it generally points to the impulse or energy given off by an inscape—another of Hopkins’s words signifying the essential meaning or uniqueness of a thing or experience.

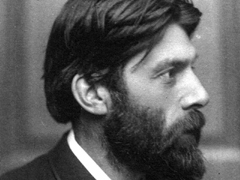

From his lyrical portrait of Hopkins’s decision to “go over” to Rome and, further, become a Jesuit, Mariani backfills with a dash of Hopkins’s family and a splash of his schooling. Neither, however, comes fully alive, nor are they fully realized. The result is that in some sense neither is Hopkins. In particular, one would have liked a fuller discussion of the religious revival that was the Oxford Movement, its efforts to renew the Anglican Church’s Catholic inheritance, and the panoply of religious currents and crosscurrents—Tractarians, Ritualists, High Church Anglicanism, Broad Church Anglicanism, and Roman Catholicism—that were so much a part of the intellectual milieu at Oxford when Hopkins was there, and how the young man worked his way through them to his ultimate decision to convert. Additionally, a fuller discussion of Hopkins’s Oxford life beyond the conversion decision would have helped round out the spiritually anguished but religiously and academically questing Hopkins, especially a more full-bodied rendering of friends, companions, and correspondents such as the very important Robert Bridges (poet, physician, and hymn writer who became Hopkins’s editor and literary executor) and the scholar Alexander Baillie, as well as Oxford tutors such as art and literary critic Walter Pater and the classicist and theologian Benjamin Jowett.

Robert Bridges |

We do get this description of Hopkins at school as he contemplates conversion: “And while he (Hopkins) can joke and banter with the best of them, he seems tired, tired beyond his years, tired of standing on the sidelines as the great appetitive world spins on.” It is also the first reference to what will be a red thread running throughout Hopkins’s life—tiredness, a weariness that seems to be part existential despair, part recurring physical illness.

Might it have something to do with Hopkins’s struggle with his sexuality? One of the curious lacunae in Mariani’s book is any serious discussion of Hopkins and sex, especially the contentious issue of whether Hopkins was homosexual. A number of writers, including critics Denis Donoghue and Brad Leithauser, as well biographer Robert Bernard Martin in his 1991 life of Hopkins, have all made the suggestion, even assertion, that Hopkins was gay. On the other hand, editor and author Justus George Lawler, in his study HOPKINS RECONSTRUCTED (Continuum, 1998), has sharply questioned the contention. It may well be irresolvable, but one wishes Mariani had taken up the issue.

Here, too, as Hopkins’s life plays out at Oxford, it might have been helpful if Mariani discussed the influence of the Victorian writer and critic John Ruskin on Hopkins’s poetry and the aesthetic theory he developed. At least one critic, Philip Ballinger, in “The Poem as Sacrament,” a monograph on Hopkins’s theological aesthetic, has argued that Ruskin may be as important as Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, and Duns Scotus, the late-thirteenth-century scholastic philosopher and theologian, in shaping Hopkins’s work.

After converting to Catholicism, Hopkins joined the Jesuits in 1868, burning most of his early poems in the process and believing that writing poetry would “interfere with my life and vocation.” Becoming a Jesuit seems to be a decision he never regretted, but as Mariani makes painfully clear, it was not generally a good fit either for Hopkins or for the Jesuits, who apparently did not know what to make of the odd and anguished young man, the eccentric but brilliant novice and, later, priest.

Drawing heavily on Hopkins’s letters and journals, Mariani is at his best as he follows Hopkins’s career in the Jesuits through a series of postings—first study, then parish and teaching assignments in four countries ending in Ireland, where he remained until his death.

After destroying most of his undergraduate poetry, Hopkins did not write again until 1875, when he was encouraged by one of his superiors to write a poem on the sinking of the German steamship Deutschland and the deaths of five Franciscan nuns who were on board, exiled from Germany by anti-Catholic laws. It is Hopkins’s first real effort at what he calls “sprung rhythm,” a rhythm generated by “scanning by accents or stresses alone, without any account of the number of syllables, so that a foot may be one strong syllable or it may be many light and one strong.” In a brilliant 12-page explication of “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” which many consider to be the best of Hopkins’s poems, Mariani makes accessible the theology and aesthetics of the very difficult verse. Hopkins submitted the poem to the Jesuit publication The Month, but it was apparently obscure and too hard for the editors to understand, and it was rejected.

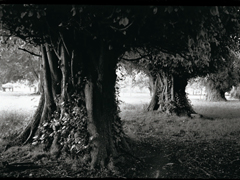

Pleasure Grounds, Clongowes Wood College, County Kildare from HOPKINS IN IRELAND by Michael Flecky, SJ |

Catholic writer Ron Hansen’s richly imagined novel EXILES (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2008) also takes as its subject Hopkins’s return to writing poetry and the shipwreck that inspired him. Hansen, best known for his powerful fiction-writing and his novels MARIETTE IN ECSTASY and ATTICUS, is also the Gerard Manley Hopkins S.J. Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Santa Clara University. His new Hopkins novel, he said recently in remarks made at Georgetown University, is “all about outsiders”—priests and nuns and writers, too, who are “not part of the general herd.” The book juxtaposes two stories of exile—the five German nuns who were persecuted at home and are en route to a country not their own, the United States, when the Deutschland went down, and the thwarted, unread and unrecognized poet-priest, with his own sharp sense of separation and estrangement, who immortalized the nuns in his verse. As Hansen imagines it, Hopkins accepted the poem’s rejection (“Whether he published his poetry or not seemed to the conscientious Hopkins another vagary over which a good Jesuit should exercise no partiality”) and went on not long afterward to write “a clutch of poems that were so original and are now so esteemed that 1877 has since been considered his annus mirabilis, Hopkins’s miracle year.”

Mariani makes for engrossing reading as he writes of the burst of creativity during the months after writing “The Wreck of the Deutschland” and before Hopkins’s ordination, in which he wrote some of the poems that have come to define his contribution to modern poetry, including “God’s Grandeur,” “The Starlight Night,” “Spring,” “The Windhover,” and the untitled sonnet “As kingfishers catch fire,” which is among the finest religious poems of the nineteenth or any century. “The kingfishers sonnet is about the Scotist individuation of things,” Mariani writes of the poem’s theological roots in the medieval Duns Scotus, “where…the opening lines flame out, and where things reveal themselves.…But more: it is about Christ playing—acting in all seriousness, at the same time delighting in the never-again-to-be-replaced distinctiveness of human beings in ten thousand separate places and revealed in the faces of those who keep God’s graces”:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves – goes itself; myself it speaks and spells

Crying What I do is me: for that I came.

I say more: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is –

Christ. For Christ plays in ten thousand places

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

But despite the incarnational glory of these poems, Hopkins continues to be plagued by a weariness that is both mental and physical. “Elation and depression: bordering on the bipolar in Hopkins’s mood swings,” Mariani notes. “For if he is capable of composing a poem like ‘God’s Grandeur,’ of singing ‘sometimes the sweetest, sweetest spells,’ his spirit can also droop as much as any caged songbird….”

On the evidence of Hopkins’s letters and journals, it is apparent the theology of Jesuit founder Ignatius Loyola, with its notion that Christian believers could encounter God in all of creation, provided as much of the theological underpinnings for his best incarnational and sacramental poetry as did Duns Scotus. At the same time, Hopkins was evidently temperamentally and physically ill-suited for the order and its exhausting regimen of study, teaching, grading papers, and parish work, including preaching and visiting the sick. The menial chores drove him, time and again, to the brink of breakdown and exhaustion throughout his short life.

The Jesuits seemed at a loss for how best to make use of the odd, eccentric but also very likable Hopkins. Certainly his devotion to Scotus put him out of the mainstream of Jesuit thinking at the time and raised suspicions among his superiors, who favored Thomas Aquinas for his understanding of the unity of all things over the individual “thisness” of Scotus: “that which makes this oak tree this oak tree only, or this rose this rose only, or this person this person only, and not another—something unique and separate, God’s infinite and incredible freshness of Creation every nanosecond of every day, world without end,” as Mariani describes it.

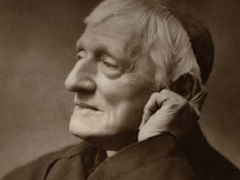

John Henry Newman |

That fact may have had something to do with Hopkins’s failure to pass, with sufficiently high marks, the exams that would allow him to become a fully professed Jesuit, a major blow to any career ambitions but perhaps also a blow to his self-esteem. His poor health, as well, seems to have contributed to his superiors’ decision not to let him go for the fourth year of theological studies and the professional certification that would bring. “And though he is heartsick over the news, he will keep this to himself like the good soldier he is and serve wherever he is sent,” Mariani writes.

“Wherever he is sent” finally meant Ireland for a “reluctant and apprehensive” Hopkins and an assignment teaching at University College Dublin, established by John Henry Newman to compete with the richer and Protestant Trinity College. But it was soul-wearying work for which Hopkins could find no purpose, Mariani writes. There are some poems that get written in what might be called Hopkins’s Irish exile, but they are much darker than his Welsh poems, more anguished and full of self-loathing though no less faithful to his vision of God. Mariani finds Hopkins in these last years of his life dwelling “on his own bouts of near madness, melancholy, darkness, despair, even thoughts of suicide.” So Hopkins writes:

I am gall, I am heartburn. God’s most deep decree

Bitter would have me taste: my taste was me;

Bones built in me, flesh filled, blood brimmed the curse.

Selfyeast of spirit a dull dough sours. I see

The lost are like this, and their scourge to be

As I am mine, their sweating selves; but worse.

Hopkins’s bleak, brooding, and beleaguered final years in Ireland have been exquisitely captured in the black-and-white photographs of Michael Flecky, S.J., a professor of photography and fine arts at Creighton University, and recently published in the book HOPKINS IN IRELAND: PICTURES AND WORDS (Creighton University Press, 2008). Drawing on letters, poems, and spiritual journals, the pictures are of country places Hopkins visited during retreats and vacations, the Dublin landscape he encountered, the monastery, college, and seminary grounds he walked, and the Jesuit community and university buildings where he lived and died. The elegiac sequence of pictures is paired with excerpts from the writings of Hopkins and his commentators to offer a visual illumination of his poetic and spiritual life.

Hopkins died on June 8, 1889, just six weeks short of his 45th birthday. He was diagnosed with typhus, but Mariani suspects it was complicated by Crohn’s disease, a sickness unnamed until 1932. Hopkins’s last words, repeated over and over, were an affirmation—or a plea to himself: “I am so happy. I am so happy.” He died unheralded and unpublished, and it was not until 1918 that Oxford University Press published an edition of 750 copies of the poems edited and introduced by his old friend, England’s then poet laureate, Robert Bridges.

A decade before his death, however, Hopkins ruminated on the question of fame in an exchange of correspondence with his friend, fellow poet, and Anglican cleric Richard Watson Dixon. “Fame,” Hopkins wrote, “is a thing which lies in the award of a random, reckless, incompetent, and unjust judge, the public, the multitude. The only just judge, the only just literary critic is Christ, who prizes, is proud of, and admires, more than any man, more than the receiver himself can, the gifts of his own making.”

Nearly a century later, John Berryman, a poet as singular as Hopkins, would appropriate Hopkins in one his last poems, a poem of his own religious conversion:

Father Hopkins said the only true literary critic is Christ.

Let me lie down exhausted, content with that.

It is an appropriate signal of how Hopkins’s fame and, more importantly, his influence have grown and spread since that first slim edition of 750 poems until now, the first decade of the 21st century, and how he has become a central part of the modern canon. While Auden pronounced himself “uneasy” at the intensity of Hopkins’s confessional mode, others celebrate and emulate what Robert Lowell called his “inebriating exuberance.” Poets as radically different as Hart Crane and Elizabeth Bishop have acknowledged their indebtedness, and his complex rhythms, his stretching of conventional structures to the near breaking point coupled with his intensely sacramental view of the world have been major influences on poetry for a century.

In 1975, Hopkins was memorialized with a plaque in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner, set between those recognizing T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden—the first Catholic since John Dryden and the first Roman Catholic priest ever to be so honored. The real honor, however, is that his poetry continues to be read, and his vision of a world charged with the presence of God continues to move and claim readers.

David E. Anderson, senior editor at Religion News Service, has also written for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on Walt Whitman, John Donne, William Shakespeare, and American religious poems.