In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Hispanic Holy Week

KIM LAWTON: For America’s burgeoning Latino community, there are many special rituals to make Holy Week, Semana Santa, come to life.

Reverend DAVID GARCIA (Director, Old Spanish Missions, Archdiocese of San Antonio): This whole week, in a sense, captures that final week of Jesus’ life and kind of helps us to walk through it with Jesus, and so that we can understand a little bit better what it means to us and how we have to live our lives.

Reverend DAVID GARCIA (Director, Old Spanish Missions, Archdiocese of San Antonio): This whole week, in a sense, captures that final week of Jesus’ life and kind of helps us to walk through it with Jesus, and so that we can understand a little bit better what it means to us and how we have to live our lives.

LAWTON: Father David Garcia is director of the historic parishes, the old Spanish missions, for the Catholic Archdiocese of San Antonio.

Rev. GARCIA: Hispanics, especially in this country and throughout Latin America and in Spain, also have popular religious devotions that help them to, in a sense, to experience a little more personally with all the senses. We can see it. We can hear it. We can almost taste it, and it’s that full use of the senses that is very distinctive of Hispanic popular religiosity.

LAWTON: The most intense part of the week begins on Holy Thursday, often called Maundy Thursday. This was when Jesus celebrated the Last Supper, a Passover meal, with his disciples on the night before he died.

Rev. GARCIA: What the church celebrates that day is the institution of the Eucharist, that is, Communion.

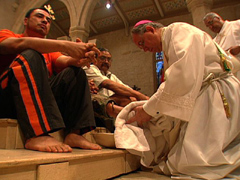

LAWTON: On this day, another central practice for many Christian traditions is a foot-washing ceremony, remembering the Gospel story of Jesus washing the feet of his disciples during the Last Supper.

Rev. GARCIA: Christ connected the Eucharist with service to others, and that’s the power of Holy Thursday—that in taking the Eucharist and in taking Communion it’s not just my little spiritual moment with God, even though that’s part of it, but it’s also a commitment to be the body of Christ for the world, to go out and to serve.

LAWTON: Many Hispanic churches also include a blessing of special bread called pan bendito, which is passed out after the service.

Rev. GARCIA: The whole idea of the pan bendito is that this is the bread that you have been given. Just as you have been given a lot of gifts, you have been given a lot of resources in your life, so now you need to go and share.

LAWTON: In the Hispanic Catholic tradition, Good Friday is especially important, and so many Latino churches actually begin their Friday observances on Thursday. At San Antonio’s historic San Fernando Cathedral, after the Holy Thursday service the crowd spills out into the courtyard for a re-enactment of Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane and then his arrest.

Rev. GARCIA: The last image is a difficult image. Jesus is manhandled. Jesus is tied up. Jesus is dragged off. So you go home with this very deep sense of sorrow and reflection and suffering that is now going to be a very much a part of Good Friday.

Rev. GARCIA: The last image is a difficult image. Jesus is manhandled. Jesus is tied up. Jesus is dragged off. So you go home with this very deep sense of sorrow and reflection and suffering that is now going to be a very much a part of Good Friday.

LAWTON: On Good Friday, Latino churches typically hold a variety of services all day and into the evening. Many of those observances are held outside and in the streets. Passion plays which retell the story of the crucifixion are especially popular. San Fernando has held a Good Friday passion play for more than 275 years. Today, some 25,000 people show up for it. There are more re-enactments, telling the familiar story: Jesus standing before the Roman governor Pilate being tried, mocked, and beaten, and finally convicted.

Rev. GARCIA: The community of San Fernando includes no professional actors or actresses. They are people who are the working poor of San Antonio. They are going to be the ones cleaning the hotel rooms. They’re going to be the ones sweeping the schools floors. They’re going to be the ones driving the buses.

LAWTON: Within the Passion play is another widespread Hispanic practice, Via Crucis — the Way of the Cross. As Jesus carries his cross to the place where he will be crucified, crowds follow in procession through the city streets trying to identify with what he went through.

Rev. GARCIA: We take the city, the center of the city, just for a few moments on Good Friday, and we recreate it, in a sense we make it sacred. We make secular sacred, and in that process we become more sacred. We become more faith-filled.

LAWTON: Garcia says the traditions first came from Spain, where Catholics living under Islamic rule tried to preserve their identity by holding open-air ceremonies. When Spanish missionaries came to the New World, those traditions tied into Native American traditions of holding public rituals. Early Spanish missionaries used Passion plays to help overcome language barriers in their efforts to convert indigenous people and teach them the faith.

Rev. GARCIA: And so these plays, these dramas, these public events in the plazas, in the streets of the cities, began to take the place of kind of going into a classroom and reading a catechism book.

LAWTON: The long procession finally stops in front of the cathedral for the most dramatic moment of all — the crucifixion. Jesus cries in pain as they nail him to the cross. His mother Mary weeps nearby.

Rev. GARCIA: Often that brings all of us — I mean I’ve seen it many, many times — I cry every year. So it’s just really a wonderful kind experience. We know it’s not the real thing but what we do also know is that it calls us to share in the real thing.

LAWTON: Mourning then continues inside the church with a service called Siete Palabras — the Seven Words. Many Christians hold Good Friday meditations on the last words Jesus spoke from the cross. But here, there is a distinctive Latino flair—solemn music and liturgical dancing in the flamenco style.

LAWTON: Mourning then continues inside the church with a service called Siete Palabras — the Seven Words. Many Christians hold Good Friday meditations on the last words Jesus spoke from the cross. But here, there is a distinctive Latino flair—solemn music and liturgical dancing in the flamenco style.

Rev. GARCIA: It’s remembering our sufferings. It’s remembering that we go through so much and yet he did it before us and he knows what it’s all about.

LAWTON: And for Hispanic Catholics, the grief continues later in the evening with the traditional pesame service.

Rev. GARCIA: In Spanish, the word pesame basically is sympathy. So pesame is going to the person who has lost someone through death and giving them your sympathy. In this case it’s Mary, the mother of Jesus, the sorrowful mother. We accompany Mary in her moment of greatest sorrow, in her moment of greatest need, in her moment of greatest suffering.

LAWTON: Mary and the other women prepare Jesus’ body for burial and then, one by one, people in the congregation also come forward with their own funeral preparations.

Rev. GARCIA: It’s a spiritual experience, but it’s also very physical. It’s very bodily. Hispanics have a very — I guess in this part of the country — a very kind of an earthy spirituality. It’s a spirituality in which they want to be close. They want to be close to Christ. They want to touch him. They want to feel him. They want to speak to him as if he’s there.

LAWTON: Garcia says all the services on this day are intended to drive home the magnitude of what happened with the Crucifixion.

Rev. GARCIA: Good Friday needs to be heavy, it needs to be tough, and it’s good for us. It connects you with the fact that this world is basically — the human experience is basically one of suffering.

LAWTON: Saturday is traditionally the quietest day on the church calendar. Some Christians gather in the evening for a candlelight vigil symbolizing the darkness that will soon give way to the light of the Resurrection, and then finally Easter Sunday and the celebration of the Christian belief that Jesus rose from the dead. The flowers of grief become symbols of life and joy. In Catholic churches the priest sprinkles holy water on the crowd, a reminder of the connection between baptism and Christ’s resurrection.

Rev. GARCIA: We now celebrate his new life. We celebrate his resurrection, that life is given to us in baptism, and now we’re called to live that life in the world, and so the whole idea of the sprinkling of the water upon us — that’s the power of Easter.

LAWTON: Garcia says the range of Holy Week emotions and the physical act of participating in all the observances have a profound spiritual impact.

Rev. GARCIA: It’s like I’ve gone through this spiritual renewal, this spiritual experience once again, and I’ve touched, I’ve touched the very foundation of my faith.

LAWTON: I’m Kim Lawton reporting.