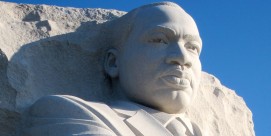

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Fifty years ago at the beginning of America’s civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. went to India to walk in the footsteps of one of his heroes, Mohandas Gandhi, who had led India’s successful struggle for independence from Britain. Dr. King was strongly influenced by Gandhi’s teachings of nonviolent resistance. Recently, Dr. King’s son and many civil rights veterans revisited India to honor both King and Gandhi. Fred de Sam Lazaro was there.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The delegation was a who’s who of the civil rights era, among them John Lewis, Andrew Young, as well as Martin Luther King III retracing the steps of his iconic namesake who’d come 50 years ago to pay homage at this shrine to Mahatma Gandhi in New Delhi.

MARTIN LUTHER KING, III (speaking to group): My dad said that he came to many countries around the world as a tourist but came to India as a pilgrim.

DE SAM LAZARO: His father’s visit to India may be a little known footnote from an eventful period in American history. But it was a pivotal event for the leader of the civil rights movement.

Dr. CLAYBORNE CARSON (Historian, Stanford University): It really allowed him to get his credentials as a Gandhian, which was very important to him. He saw himself as a follower of Gandhi, someone who had learned a great deal from Gandhi. So going to India was crucial for him because he felt that he would be judged by Gandhi’s followers and that they would understand him to be someone who was carrying on that tradition.

DE SAM LAZARO: For King in 1959, India — independent only since 1947 — was a beacon of hope. Even though Gandhi was assassinated barely one year after independence, his civil disobedience approach had successfully liberated India from British colonial rule. King was influenced by such nonviolent tactics as Gandhi’s famous 200-mile march to protest the salt monopoly, which made one of life’s basic necessities unaffordable for many Indians.

King’s visit with Gandhi’s followers invigorated the American civil rights movement. Former U.S ambassador and Atlanta mayor Andrew Young was a King lieutenant.

Ambassador ANDREW YOUNG: Dr. King talked about this trip all the time, and he talked about the influence that Gandhi had on his life. He learned the meaning of the heritage that he had grown up in, and he talked about that. In fact, our whole civil rights movement — the March on Washington — was a reflection and effort on our part to imitate Gandhi’s Salt March to the sea. Our teachings, the methods that we used all came from the life and the spirit of Mohandas Gandhi.

DE SAM LAZARO: Fellow civil rights era veteran now Congressman John Lewis said the Gandhian influence profoundly shaped his own values.

Representative JOHN LEWIS (D-Georgia): If it hadn’t been for Gandhi and Dr. King, I wouldn’t be a member of the U.S House of Representatives. The teaching of Gandhi changed my life forever, made me a better human being, and today I can say in spite of the arrests — I was arrested 40 times during the ’60s, beaten, left bloody and unconscious — but the teaching of Gandhi freed me, liberated me, and I don’t feel any ill feeling or malice or hatred toward anybody.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s a Gandhian value that transcended religious and cultural traditions as distant as King’s Christianity and the Hinduism Gandhi was born into.

Dr. CARSON: One of the things about King and Gandhi is that you can follow them without being either a Christian or a Hindu. I think that one of the strengths that they brought is that they understood the universal applications of those ideas that came out of a cultural tradition, and that’s what’s made them — that’s what allows someone to listen to even to a King sermon and be inspired by it even if one is not a Christian.

DE SAM LAZARO: There’s no known footage of the 1959 King visit, but a radio address was recently discovered in the archives of India’s radio network.

Voice of MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR (audio from 1959 radio broadcast): Since being in India I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity. In a real sense, Mahatma Gandhi embodied in his life certain universal principles that are inherent in the moral structure of the universe, and these principles are as inescapable as the law of gravitation.

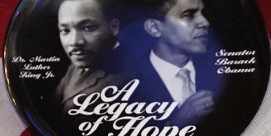

DE SAM LAZARO: Half a century later, this trip to India took place after a historic American election, and the link — Gandhi to King to Obama — was plain to see for many.

Ambassador YOUNG (speaking to delegation): He had on his wall of his Senate office pictures of Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi and Abraham Lincoln.

GEORGE DUKE (Jazz Musician, speaking to audience): One thing I know for sure — Gandhi and Martin Luther King understood the blues.

DE SAM LAZARO: The 50-year commemorative trip sponsored by the State Department included musical performances by George Duke, Herbie Hancock, a number of up-and-coming musicians joined sometimes by Indian artists like tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain.

Throughout the two-week tour across India, one question came up frequently: What would Dr. King think about India today? Would he see much change over 50 years?

Mr. KING III: Even in a country like India, which has so much in terms of technology and information today — opportunity — there’s still immense poverty, and that would not—that would be very painful, I believe, to him and my mom.

DE SAM LAZARO: Nor, in fact, would King likely be pleased at an India today that is a nuclear armed military power — repudiation, it would seem, of a plea he made in his 1959 radio broadcast here.

Voice of MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. (audio from 1959 radio broadcast): Just as India had to take the lead and show the world that national independence could be achieved nonviolently, so India may have to take the lead and call for universal disarmament. And if no other nation will join her immediately, India may declare itself for disarmament unilaterally. Such an act of courage would be a great demonstration of the spirit of the Mahatma and would be the greatest stimulus to the rest of the world to do likewise.

Dr. CARSON: One of the ironies is that as King met with Nehru and other followers of Gandhi who were now part of the government of India, he found that in some ways he was more Gandhian than they were, because they were now in power. They were now not committed to the kind of course that Gandhi had advocated — the non-industrializing that he felt that that was the wrong course for India to take.

DE SAM LAZARO: Similarly, Carson says, King would be a thorn in President Obama’s side today since he opposed all uses of military force. That’s the thing about visionaries like Gandhi and King, he says. They’re easy to admire, but difficult to emulate.