MARY ALICE WILLIAMS, guest anchor: In inner cities across the US high numbers of African-American men are caught up in the criminal justice system. It’s costly to keep them in prison. It’s also costly to the communities they leave behind — and return to. Phil Jones reports.

PHIL JONES: Welcome to Brownsville — a pocket of poverty inside Brooklyn, New York, a place where crime and prison often are a way of life.

RONALD HERRON: Both my parents were drug addicts. My father wasn’t at home.

DEJUAN SMITH: I went to prison for murder in the second degree.

NATHANEL RICE: The first time for robbery — two years; second time for robbery —12 years; third time for drug possession.

VINCE MATTOS (Community Activist): I was out hustling narcotics. What I would have to tell Mom is, “Look, I found a whole bunch of money!” I would see Mom crying because she was behind on bills or something like that. I would come in and say, “Mom, look I found x, y and z.” You know, she was like, oh, you know, “God is good” — this and that.

JONES: But Vincent Mattos’s mother is proud of her 42-year-old son.

Mr. MATTOS (speaking to men): Hey brothers. How you doing?

JONES: He now roams these troubled streets as a community activist. He knows the turf.

Mr. MATTOS: Young men that’s out on the corner from sun-up to sundown, falling back to do what they know to do to earn a living because there’s no jobs for them. There’s no helpful reentry program that’s in place right now. Whatever you want, you can get it on this strip. Drugs, sex, and guns, that’s what’s major out here.

JONES: What else is major — the pervasive presence of police with the task of arresting the bad guys and putting them behind bars. There is no doubt that police activity decreases crime. But is there a tipping point, when legitimate law enforcement, designed to protect the public, may have unintended consequences: promotion poverty, even more crime?

ERIC CADORA (Director, Justice Mapping Center): The current overuse and overdependence on criminal justice is a complete failure. It’s having no impact on these issues of public safety and crime. That’s not to say there isn’t a need for a level of criminal justice. But this radical overuse is not accomplishing those goals.

JONES: In the 1970s, there were about 200,000 inmates in US prisons. Today there are about two million. For years law enforcement used crime mapping to target places where the crimes were being committed. Eric Cadora, director of an organization called the Justice Mapping Center, is an advocate for sentencing reform and prison alternatives. He proposed another use for mapping.

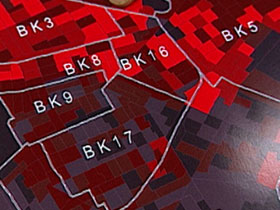

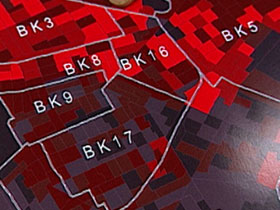

Mr. CADORA: I said, “Well, what if we don’t do crime mapping? What if, instead, we mapped where people lived who are going into jail and prison every year?” When we started doing maps of where people lived, we found hugely concentrated neighborhoods where vast majorities of people were going to prison and jail and coming back, and other neighborhoods where nearly none were.

This is New York City. The brightest red show the highest rate per thousand adults, male adults, admitted to prison for a single year. Let’s say there are about 100,000 people living in Brownsville — about half of them are male, that’s about 50,000. About — between 10 and 13 percent are going to prison and jail every year.

JONES: This increased prison population has come at a staggering cost to taxpayers.

Mr. CADORA: We can now calculate, block by block, how much we’re spending to remove and return people en masse from and back to that block.

JONES: This cluster of housing projects is what Caldora calls a “Million Dollar Block.”

Mr. CADORA: We found about 150 individual blocks in New York City for which we were spending more than $1 million a year to remove and return people to prison and jail.

JONES: Cadora uses dark red to show the concentrations in other states. They are maps that call for new directions.

Mr. CADORA: What these maps have done is accumulate the effect over the course of a year of a criminal justice and imprisonment system. What’s heated up here is a mass migration with the costs of having to move back and forth from this neighborhood to prisons upstate and back. So what we’re seeing here is constant grappling with resettlement, with disruption, cost of split families, tough health care.

JONES: Greg Jackson, another civic activist and a life-long resident of Brownsville, doesn’t need a map. He’s seen his own community imprisoned.

GREG JACKSON (Community Activist): Incarceration is not just the individual going to jail, but it’s the whole family going to jail, for Brownsville. Everybody’s suffering from it.

JONES: How’s that?

Mr. JACKSON: Because when this individual comes out of jail he still can’t find employment. And that person, the kids he left behind, the parents he left behind, the wife he left behind, they all suffer in the interim. So, when he comes out you think, “Wow, it’s a good time, my father’s coming out of jail, my mother’s coming out of jail.” There’s nothing good about it.

JONES: For one thing, felons aren’t allowed to live in these public housing projects, although some do. Others end up homeless, and most are jobless. Ask Dejaun Smith, still struggling eight years after his release.

Mr. SMITH: I’ve done odd jobs like — I couldn’t even begin to tell you how many. I went to an interview several months ago, and once they learned about my conviction they looked at me like, “Don’t call us, we’ll call you.”

JONES: After decades of hard-line policies on crime — tough justice — more and more communities are looking into what is called Justice Reinvestment.

Mr. CADORA: Let us take the investments that had been built up over the years from criminal justice, redirect them to investments in civil institutions in those neighborhoods — better schools, better health care, better mental health support, and so on. In many of the states where the Justice Reinvestment initiative has taken root, prison populations are either dropping or the trend line in growth has been radically reduced, and that’s from Connecticut to Kansas — liberal to conservative.

JONES: Most of the crimes are connected to violence, drugs, and alcohol. But researchers found another culprit for the increased prison populations.

Mr. CALDORA: We found states where 60 to 65 percent of everyone entering prison each year were entering as a result of a revocation of parole and probation.

JONES: That was the case in Kansas, so legislators passed a new law — a new direction —committing taxpayer dollars to cities and communities that change parole and probation regulations that’ll reduce the prison population by 20 percent.

Mr. CALDORA: That’s kind of what the reinvestment project is about. It’s about saying, “Look, if you can reduce it, we’ll give you the money to keep reducing it.”

JONES: According to Caldora, states are being forced to rethink their hard line throw-the-criminals-in-jail attitude because, especially in these hard economic times, the criminal justice system is too costly, both financially and psychologically.

Mr. CALDORA: They realize that this overwhelming overuse of criminal justice is one of the greatest threats to sort of civil society.

JONES: This threat to society, this impact on communities in prison, can be felt on the streets and inside the crowded housing projects. We met Matoka Belton. She didn’t want us to see her three children. Their father went to prison.

(to Ms. Belton): What was he in prison for?

MATOKA BELTON: A number of things, and it was due to survival.

JONES: What was impact on the children of him being away?

Ms. BELTON: It’s hard because they’re like, you know, what “school” is this, because you try not to say he’s in prison. “What school is this that they don’t come home? College?” But then it comes to the point where they’re a certain age and you can’t lie anymore. I was once an inmate myself. I know what it was like for my children to feel like, “Wow, my mother’s not here. Why can’t mommy come home with us?” It’s hard to leave a visit.

JONES: It’s a cruel cycle — poverty, crime, prison — passed from one generation to the next. A child whose parent went to prison is likely to end up behind bars too.

Mr. MATTOS: When you look at a kid and you say, “How could that kid, you know, have done such a crime like that?” Because he was never really told that was something wrong to do. He never celebrated Christmas with the family or sat down at the dinner table with the family.

JONES: About 700,000 inmates come back home every year. Most are unprepared for re-entry, and their communities are unprepared for their return. As the US government is making huge investments in industries and businesses, it is now being forced to also address a broken justice system, a system in desperate need of a stimulus package of sorts — justice reinvestment.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Phil Jones in Brooklyn, New York.