In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Painting a Jewish Memory Book

BOOK AND EXHIBITION REVIEW

by Juliana Ochs Dweck

“Hey! There was a big world out there before the Holocaust,” Mayer Kirshenblatt calls out in his recent book about Jewish life in Poland before World War II.

In 1990, when Kirshenblatt was 73, he began to draw to ensure that people would remember how Eastern European Jews once flourished before so many perished. At the urging of his family, he sketched his memories of life in Apt (Optów in Polish), the small town he grew up in before World War II and eventually left. He painted his mother and the town’s wigmaker, men praying in the besmedresh (study house), and prostitutes in the marketplace. As a child, Kirshenblatt spent his mornings in kheder (Hebrew school) and his afternoons in the town’s Polish public school, but he devoted almost as much time to playing hooky and exploring everyday activity in Apt. In an exceptional exhibition and ambitious companion book of the same title, They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland before the Holocaust (University of California Press), we join Kirshenblatt as a young boy. We go on meandering walks with him, taking in the spectacle of the livestock market, eavesdropping on gossiping women, inspecting the components of a shoe and the workings of a whistle.

In the 1930s, Apt was largely a Jewish town, with 6,500 Jews and 3,500 Christians, so much of daily life was Jewish life. Kirshenblatt illustrates the minutiae of formal and informal Jewish ritual in multicolored detail. Mikve: Thursday, Women’s Day depicts a women’s weekly ritual bath. The mikve was a square pool, four feet deep and heated by a wood-burning oven. Women would bring their own soap and towel and, with the bucket provided, rinse themselves with hot soapy water and then step into the water. Shlugn Kapures: Yom Kippur Eve shows Kirshenblatt’s family as they swing a chicken above their heads, a Yom Kippur ritual that symbolically transfers one’s sins to the fowl.

In Apt, Jewish life was intertwined with Christian life. Images such as Funeral of the Father of My Christian Friend, depicting the interment of the father of Kirshenblatt’s childhood fiddle partner, demonstrate the pre-war intimacy between Jews and Christians. Daily interaction in the Polish village was often cluttered and eccentric. There were the tomatoes Kirshenblatt’s mother forbade her sons from eating, deeming them trayf (not kosher) because she saw them growing in the church organist’s garden. There was the town’s main synagogue, which had a sunken floor: one had to descend four steps to enter. This made the inside of the sanctuary feel imposing without dominating the town church’s exterior, which was prohibited.

Mayer July’s folksy memory paintings and the lyrical narratives that accompany them have a frequently idealized sweetness and beauty. Their timeless quality is reinforced by an unvarying date, 1934, inscribed on nearly all of the paintings, as if Kirshenblatt’s entire childhood happened the year he left Apt and emigrated to Cananda. But Kirshenblatt does not sanitize pre-war life. He reveals and revels in “the carnivalesque side of life,” as Jewish studies professor Jeffrey Shandler calls it on the exhibition’s audio guide. We see this in the kleptomaniac who slips a herring down her bosom and in the depiction of Baynish the Drummer catching Yankele Zishes in bed with his wife. Kirshenblatt’s accompanying narratives are assiduous but also relaxed and episodic, expressed, as his daughter, New York University professor Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, writes in her afterword to the book, in the “realm of living speech.”

Kirshenblatt’s animated paintings are so bulging with vivid detail that, like stories themselves, they invite careful perusal (something the exhibition’s large paintings encourage). Their intricacy betrays a life and a memory that is about learning and exploration, not knowledge and erudition. They are about feeling more than fact.

Just as Kirshenblatt’s illustrations intimate the practice and process of life in Apt, his art is itself the result of a long, collaborative process. In 1967, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett began “listening with love” to her father’s stories of life in Apt. In the ensuing decades, Mayer Kirshenblatt’s entire family became involved, hoping that painting would alleviate his bouts of depression. His wife sent him to painting lessons, Kirshenblatt-Gimblett’s husband provided him with art supplies, and another son-in-law built racks for his canvases.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett helped her father build the scaffolding for his memory by eliciting stories through word associations, encouraging tales to become sketches and sketches to inspire paintings. This would provide a foundation for Mayer Kirshenblatt’s own recollections and also for stories he elicited from childhood friends and from the town’s memory book. The result is a collective autobiography, a story told in the “third voice” with multiple points of view intertwined to tell one story.

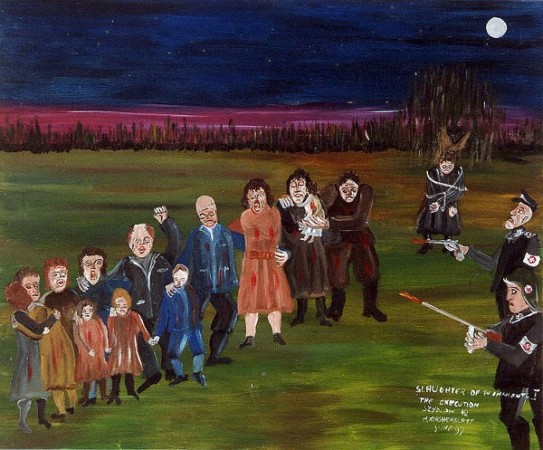

Kirshenblatt’s own memory of Apt ended in 1934, when he, his three brothers, and his mother traveled to Toronto to join his father, who had fled in 1928 to escape the wrath of a loan shark. It was only through letters that arrived after the war that Kirshenblatt learned the fate of his family members who remained in Poland. In Slaughter of the Innocents II: Execution at Szydlowiec 1942, he depicts the bloody execution of his family by the Nazis: “The Germans took the whole family out to a nearby field. They lashed my grandmother to a tree and, before her very eyes, they shot her entire family. Then they shot her.”

But Kirshenblatt himself is not a Holocaust survivor, and the execution scene is a memory he borrowed from survivors and reports. Despite this, in Kirshenblatt’s painting borrowed memories and collective memories become as emotional and painstaking as his own.

In Jewish tradition, memory has long been preserved and transmitted through ritual and liturgy, passed on not only through texts but also through religious practice. Jewish rituals, such as the Passover meal, are an active way Jews share the past with future generations. It is how Jews heed the injunction zakhor, “remember,” which appears in the Hebrew Bible and has been echoed as Jews vow not to forget the Holocaust.

But in Mayer Kirshenblatt’s collective autobiography and in the exhibition of his work, we see that Jewish memory is also stored and transmitted through art, through the creative expression of painting. When Kirshenblatt paints Jewish rituals and Jewish life, whether in their joy or their sadness, he preserves both his own memories and also the collective memories of the Polish Jewish community. In Mayer July, painting becomes Kirshenblatt’s own religious practice of remembrance.

“They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland before the Holocaust” was organized by the Judah Magnes Museum in Berkeley, California. It runs through October 1, 2009 at the Jewish Museum in New York City.

Juliana Ochs Dweck has also written for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on Hebraica in Philadelphia and the Rose Haggadah at the New York Public Library.