In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

The Real Paul

REVIEW ESSAY

REVIEW ESSAY

The Real Paul

by Allen Dwight Callahan

It has been a big year for the Apostle Paul.

According to the Roman Catholic Church, 2009 is his year—or more exactly the liturgical year from June 28, 2008 to June 29, 2009 was his year, marking the 2,000th anniversary of his birth.

The party got started in Rome in 2007, when Pope Benedict XVI announced a special jubilee year dedicated to Paul at a service at the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls. Beneath the church’s main altar Vatican experts had unearthed what they said was evidence that a roughly cut marble sarcophagus is the tomb of St. Paul, believed to have been martyred nearby.

The sarcophagus, which dates back to at least AD 390, was the subject of an extended four-year excavation completed in 2006. “Our objective,” said Vatican archaeologist Giorgio Filippi, “was to bring the remains of the tomb back to light for devotional reasons, so that it could be venerated and be visible.” Many pilgrims who came to Rome during the Catholic Church’s 2000 jubilee year had expressed disappointment upon finding St.’s Paul’s tomb inaccessible for veneration.

This June the pope said a scientific test “seems to confirm” that the remains in the sarcophagus belong to Paul. If the fourth-century tomb had contained fourth-century bones—three centuries too late to be Paul’s—it might have dampened the enthusiasm of the faithful. But Benedict’s announcement of a jubilee year for Paul had already created an excellent business opportunity for the fitful industry of Pauline scholarship.

Benedict emphasized in his vespers announcement of the Pauline year that it would have an important ecumenical dimension, explaining that “the Apostle of the Gentiles, who dedicated himself to the spreading of the good news to all peoples, spent himself for the unity and harmony of all Christians.” In that spirit John Dominic Crossan, an Irish Catholic biblical scholar and former Roman Catholic priest, and Marcus Borg, a Protestant biblical scholar and Episcopal canon theologian, teamed up to coauthor The First Paul (Harper Collins, 2009).

Borg, as the Protestant principal of the duo, writes, “As I look back on my experience of growing up Lutheran, it is clear that I was taught to see Jesus, God, and the Christian gospel through a Pauline lens as mediated by Luther.” Crossan recalls his days as a young priest in 1959 “when I first stood in St. Peter’s Square in Rome and looked at the statues of St. Peter … and St. Paul.” Together Borg and Crossan claim to cut through the hagiographical accretions to get to the original Paul, the first Paul, and say “our common hope is that we can get Paul out of the Reformation world and back into the Roman world.”

For Borg and Crossan there is more than one Paul in the New Testament and no less than three Pauls. The first is “the radical Paul,” author of the seven genuine letters that go under his name: Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, 1 Thessalonians, Philippians, and Philemon. Then there is “the conservative Paul” of 2 Thessalonians, Ephesians, and Colossians (“the disputed letters”) and “the reactionary Paul” of the Pastoral Epistles.

Some recent commentators do not mark differences between the Paul of the seven undisputed letters, the Paul of Ephesians and Colossians, the Paul of the Pastoral Epistles, and the Paul of Acts, differences explained with characteristic clarity and elegance by Garry Wills in his What Paul Meant (Viking, 2006). Yet among some entries to the ample bibliography of the Pauline Year, there is still some slippage. Raymond Collins’s The Power of Images in Paul (Liturgical Press, 2008), as its table of contents makes clear, treats the Magnificent Seven as authentic, devoting a chapter to each. The first chapter opens with a quotation from Titus 1:1-3, which Collins describes without further comment as having been written “toward the end of the first century, CE” by “an anonymous author.” But Collins freely refers to Acts to document that Paul was born in Tarsus and was a disciple of Gamaliel and a devotee of the Jerusalem Temple. Stephen Finlan, in The Apostle Paul and the Pauline Tradition (Liturgical Press, 2008), makes much of the importance of distinguishing the different sources of Pauline tradition and the theological difference that makes, without explicitly endorsing the judgment that the authentic Paul is the Paul of the seven letters.

Borg and Crossan, for their part, avidly endorse the persona of the seven-letter corpus as the real Paul, an anti-imperialist advocate of radical equality in imitation of his Lord Jesus Christ: “In Paul, the mystical experience of Jesus Christ as Lord led to resistance to the imperial vision and advocacy of a different vision of the way the world can be.”

Borg and Crossan, for their part, avidly endorse the persona of the seven-letter corpus as the real Paul, an anti-imperialist advocate of radical equality in imitation of his Lord Jesus Christ: “In Paul, the mystical experience of Jesus Christ as Lord led to resistance to the imperial vision and advocacy of a different vision of the way the world can be.”

But the best that has been thought and said about Paul’s purportedly anti-imperialist project has already been thought and said in a number of scholarly treatments in the last decade. The seminal collection of essays edited by Richard Horsley, Paul and Empire (Trinity Press, 1997), comes most readily to mind. Horsley and company first raised the question and set the scholarly agenda for answering it. The First Paul, subtitled “Reclaiming the Radical Visionary behind the Church’s Conservative Icon,” promises more of the same, if not better. But it is neither, and for one simple reason: the radical Paul of Borg and Crossan is not really very radical at all. This becomes painfully clear, among several other instances that could be adduced, in their contorted exegesis of Roman 13:1-7, Paul’s infamous exhortation to obey ruling authorities—read the Roman imperial regime—because they are “ordained of God,” who has given them the sword to enforce law and order.

Borg and Crossan explain that Paul feared his Roman audience would resort to “violent tax revolt” against Rome: “Paul is most afraid not that Christians will be killed but that they will kill, not that Rome will use violence against Christians but that Christians will use violence against Rome.” This danger of violent revolt whips Paul into a “rhetorical panic’ and causes him to “make some very unwise and unqualified statements with which to ward off that possibility”—the possibility that church folk in Rome would use their marginalized, persecuted faces to scuff the brass knuckles of Roman state terror. The hermeneutic here would be hilarious if Paul’s “statements” in this toxic text were not so “unwise and unqualified.” With radicals like this, who needs reactionaries?

The authors also identify a fourth Paul, the globetrotting hero of the second half of the book of Acts. The several and in some cases irreconcilable differences between Paul’s representation in Acts and his self-representation in his letters are treated at some length by Borg and Crossan in their third chapter, “The Life of a Long-Distance Apostle.” These differences have led some scholars to conclude that Paul’s letters and theology were either unknown to or ignored by the writer of Acts, who has woven a text about Paul’s career using threads of legend along with the whole cloth of his own imagination. Yet Borg and Crossan write, “Our primary source will be the seven genuine letters, supplemented when appropriate by Acts.” This begs the question, of course, of how Borg and Crossan know when it’s appropriate—a question they don’t answer in their book. This unresolved methodological issue must leave us in doubt about any conclusions they draw from harmonizing the first Paul and the fourth.

Consider only one of a number of dubious instances: the question of Paul’s Roman citizenship. Acts has Paul telling a Roman centurion “I was born a [Roman] citizen” (Acts 22:25-29). Reading this with the strident notice from the mouth of Paul elsewhere, “I am a Jew from Tarsus in Cilicia, a citizen of an important city” (Acts 21:39), we get the point: Acts is at pains to show that Paul is no low-status bumpkin from some jerkwater—as were Jesus and his first followers, incidentally—but the son of a metropolitan center, Tarsus, and a citizen of the empire. Yet Borg and Crossan point out that Paul never claims to be a Roman citizen in any of his letters. Indeed, there is evidence to the contrary: Paul writes that “three times I was punished, beaten with rods” (2 Corinthians 11:25), a corporal punishment the Romans inflicted only on non-citizens. The author of Acts, in spite of himself, relates that Paul was “beaten with rods” in a Philippian jail (Acts 16:22). Are we to read Acts against Paul on this question of Paul’s Roman citizenship? Or are we to read Paul against Acts—and Acts against itself?

Borg and Crossan simply roll their own here, with what characteristically follows from rolling one’s own: selective figments of reality in more vivid colors, fleeting delirium, and occasional outbursts of goofiness. In the selective figments category goes Paul’s martyrdom. “It is not surprising that Paul, like Jesus, was eventually executed by Rome,” they write. But the circumstances surrounding Paul’s death are completely mysterious, and neither the New Testament nor contemporary documents say anything about it, let alone that it was the consequence of an imperial capital sentence. On this question, as Borg and Crossan concede, they are “on the borderline between tradition and scholarship, guess and conjecture.”

In the mild delirium category goes what Borg and Crossan call Paul’s “Nabatean mission.” Paul writes to the Galatians that after receiving his life-changing revelation of the Lord Jesus Christ, he “went away at once into Arabia” (Galatians 1). Borg and Crossan assert that this is Paul’s first mission, “in immediate obedience to his vocation as Apostle to the Gentiles,” the Gentiles in this case being the Nabatean Arabs. Paul writes that he escaped the clutches of the Nabatean Arab king Aretas by being let down over the wall of Damascus in a basket (2 Corinthians 11:32-33), an unceremonious departure mentioned in Acts 9:23-25. Yet, as the authors admit, “Paul passes over this first mission in silence, and Luke [i.e., the writer of Acts] never mentions it at all.”

In the mild delirium category goes what Borg and Crossan call Paul’s “Nabatean mission.” Paul writes to the Galatians that after receiving his life-changing revelation of the Lord Jesus Christ, he “went away at once into Arabia” (Galatians 1). Borg and Crossan assert that this is Paul’s first mission, “in immediate obedience to his vocation as Apostle to the Gentiles,” the Gentiles in this case being the Nabatean Arabs. Paul writes that he escaped the clutches of the Nabatean Arab king Aretas by being let down over the wall of Damascus in a basket (2 Corinthians 11:32-33), an unceremonious departure mentioned in Acts 9:23-25. Yet, as the authors admit, “Paul passes over this first mission in silence, and Luke [i.e., the writer of Acts] never mentions it at all.”

In the occasional goofiness category is the chain of “conjecture” Borg and Crossan borrow from William Mitchell Ramsey, an Oxford classical archaeologist who flourished at the turn of the twentieth century. What Paul called his “weakness in the flesh” (Galatians 4:13) and “thorn in the flesh” (2 Corinthians 12:7) were recurring bouts of malaria he had contracted in the marshes in his hometown of Tarsus. As noted already, Paul never mentions his home town in any of the letters and, like most of us, refuses to go public with exactly what his “weakness in the flesh” was.

So why even use Acts in a historical reconstruction of Paul? I’m reminded of the Groucho Marx joke about the man who goes to a therapist because the man’s brother thinks he’s a chicken; the man rejects the therapist’s offer to cure the brother because, he says, the family needs the eggs. One reason New Testament scholarship needs the eggs, as it were, is that Acts provides a story, a narrative upon which to hang Paul’s disjointed discourse about himself. Without Acts, we are left with but a baker’s dozen of undated letters—no Pauline story, no Pauline biography and, most important for the business of the Pauline Year, no Pauline itinerary.

The travelogue of Acts furnishes the itinerary for a Pauline pilgrimage, from Palestine to Turkey to Greece and to Rome, the capital of Roman Catholic Christianity. That’s a lot of frequent flier miles, hotel reservations, exotic liquors, luxurious rugs, and overpriced trinkets. But caveat emptor: there is about as much evidence for Paul’s travels in Aegean tourist traps as there is for Paul’s “Nabatean mission.”

The Jesuit magazine America devoted an entire issue to the observance of the Pauline Year (November 10, 2008), in which a coterie of Catholic scholars tackles Paul’s toughest PR problems. In his contribution, John C. Endres, professor of sacred scripture at the Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley, California, puts the best face on the Pauline pilgrimage in Turkey, where Paul spent so many of his travel miles (“In His Shoes: A Pilgrim’s Guide to Some Pauline Sites”). Endres’s sunny excursions notwithstanding, the fact is that in Turkey those places associated with Paul bear precious little witness to his historical presence. The modern Tarsus, “birthplace of St. Paul,” is a crummy vestige of its ancient self. Its one monument to the apostle, St. Paul’s Well, is a water-bearing borehole in the ground.

Many of the various whistle stops on Paul’s Turkish itinerary lack any sign that “Paul slept here.” Archaeologists have only begun to dust off the remains of ancient Laodicea and Colossae, whose ancient Christian communities Paul commanded to exchange a copy of one of his letters (Colossians 4:16). As for the cities on Paul’s Galatian tour (see Acts 14), of Iconium Endres admits that “little of the former Roman city remains visible,” and the ancient cities of Lystra and Derbe remain unexcavated. Even the venerable Ephesus proves emblematic of Turkey in general: the city has much to offer, but little to offer the pilgrim venerating St. Paul.

But no matter. On the pilgrimage tour the radical Paul, the conservative Paul, and the reactionary Paul take a back seat to the missionary Paul of Acts. Careful readers of the New Testament may split the differences as Borg and Crossan do, picking and choosing those elements to be included in an alternative myth of the radical Paul, sliced and diced by historical criticism.

Or all these ingredients may be thrown into the high-speed blender of ecclesiastical tradition and puréed into orthodoxy. Such is the venerable modus operandi of Pope Benedict, whose erudite but pious portrait of Paul in his book Saint Paul (Ignatius Press, 2009), an edited compendium of twenty of his general audiences over the past year, is untroubled by the apparent contradictions that occupy Borg and Crossan.

Without qualm, Benedict reads Acts as the historical itinerary for all of Paul’s missionary journeys. In his treatment of the Pastoral Epistles, he acknowledges that “most exegetes today are of the opinion that these Letters would not have been written by Paul himself”; “they reflect his legacy for a new generation,” and “some parts … appear so authentic that they could have come only from the heart and mouth of the Apostle.” A more felicitous description of ancient forgery has never been written. As for Paul the martyr, though “the New Testament writings tell us nothing of the event…ancient Christian tradition witnesses unanimously that Paul died as a consequence of his martyrdom here in Rome.”

Benedict’s account of Paul’s showdown with Peter in Antioch is a masterpiece of spin control. Paul’s tantrum in Galatians, in which he twice calls Peter “a hypocrite” (Galatians 2:11-13), only shows “the veneration and at the same time the freedom with which the Apostle addresses Cephas and the other Apostles.” Reading Paul’s appeal to tolerance in matters of kosher observance in Romans 14, the pope points out that “in writing to the Christians of Rome a few years later…Paul was to find himself facing a similar situation and asked the strong not to eat unclean foods in order not to lose or scandalize the weak.…The incident at Antioch thus proved to be as much a lesson for Peter as it was for Paul.” The row in Antioch was not an apostolic smack-down, but “sincere dialogue, open to the truth of the Gospel.”

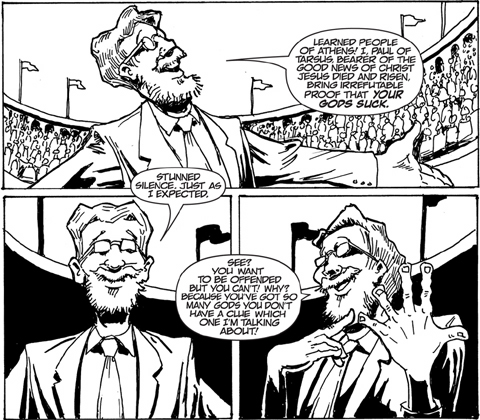

In the pope’s treatment, Paul’s schizophrenic symptoms—his violent outburst, impaired judgment, and persecution complex—go untreated. Borg and Crossan, as we have seen, engage in a literary lobotomy, surgically removing the more troubling tissue from his letters. But in his graphic novel, Blinded: The Story of Paul the Apostle (Seabury Books, 2008), writer and illustrator Steve Ross does something entirely different. He lets Paul rant and rave until he administers his own talking cure of sorts.

Ross’s narrative follows that of Acts, but the story is updated, told in black and white with contemporary color. We begin with Saul Tarsus, heartless agent of a hopped-up Homeland Security unit that seeks out and destroys partisans of the clandestine Jesus movement. After being almost killed and temporarily blinded in an auto accident, Saul strives to understand his near-death experience. With a new name and new angst, he sets out to finds “some answers.” Along the way he’s recruited by an evangelistic sideshow, chased by military brass, arrested, jailed, and water-boarded. He barely escapes being buried in the rubble of a less-than-surgical air strike and embarks on a preaching career that becomes a trail of provocations. Paul talks down slaves in revolt against their wealthy master, Jason, in Thessalonike and convinces them to become “slaves of Christ.” Their enslavement then becomes all the more unbearable, and they again rebel. In Athens, Paul seeks to sway his hearers by offering “irrefutable proof that your gods suck.” In Corinth, he turns a humble, common meal into a wildly popular supper club of eschatological enthusiasts. He then enrages the entire membership by announcing that the imminent end of the world “has been postponed.” In Ephesus, he provokes a pious pagan mob by off-handedly dissing the local deity. Later, his preaching in Rome sets off a fundamentalist pogrom. As Paul himself plaintively observes, “What am I doing wrong? I preach love. I get hate. I preach communion. I get division. I preach compassion. I get revenge.”

Ross’s narrative follows that of Acts, but the story is updated, told in black and white with contemporary color. We begin with Saul Tarsus, heartless agent of a hopped-up Homeland Security unit that seeks out and destroys partisans of the clandestine Jesus movement. After being almost killed and temporarily blinded in an auto accident, Saul strives to understand his near-death experience. With a new name and new angst, he sets out to finds “some answers.” Along the way he’s recruited by an evangelistic sideshow, chased by military brass, arrested, jailed, and water-boarded. He barely escapes being buried in the rubble of a less-than-surgical air strike and embarks on a preaching career that becomes a trail of provocations. Paul talks down slaves in revolt against their wealthy master, Jason, in Thessalonike and convinces them to become “slaves of Christ.” Their enslavement then becomes all the more unbearable, and they again rebel. In Athens, Paul seeks to sway his hearers by offering “irrefutable proof that your gods suck.” In Corinth, he turns a humble, common meal into a wildly popular supper club of eschatological enthusiasts. He then enrages the entire membership by announcing that the imminent end of the world “has been postponed.” In Ephesus, he provokes a pious pagan mob by off-handedly dissing the local deity. Later, his preaching in Rome sets off a fundamentalist pogrom. As Paul himself plaintively observes, “What am I doing wrong? I preach love. I get hate. I preach communion. I get division. I preach compassion. I get revenge.”

Ross holds in stereoscopic view both Paul the provocateur and Paul the littérateur by keeping an unblinking eye on Paul the visionary and the zealotry to which visionaries so easily fall prey. Paul may have been a man of vision but, concludes Ross, “for every vision, a blind spot.” Ross’s Paul becomes aware that his vision de jour is impaired; he anxiously intuits that he’s not seeing things quite right. He is sometimes very wrong, and he knows it. Thus, his desperate mid-course corrections: he strains, again and again, to be his best self in spite of himself. Again and again, he fails.

It is neither the virtue of a radical, nor the heroism of a martyr, but the pathos of a flawed man that makes Ross’s representation of Paul the Apostle compelling, even appealing, and an appealing Paul is a tour de force. Borg and Crossan concede that some find Paul “appalling.” John J. Kilgallen, professor of New Testament at the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome, begins his America magazine essay, “A Complicated Apostle,” by admitting that “when one reads or hears what Paul wrote, one often meets a personality that can seem unpleasant or even antagonizing … appearing pompous, cantankerous, superior, harsh.” Experts agree: Paul can be a difficult fellow. He exhorts love for enemies, yet is not above wishing aloud that his enemies would castrate themselves (Galatians 5:12). He calls his addressees stupid (Galatians 3:1). Though he imperiously claims to have “seen the Lord” (1 Corinthians 9:1, 15:8; Galatians 1:15-17), Paul in fact never laid eyes on Jesus of Nazareth and comes by “the word of the Lord” as he had come by everything else that had to do with Jesus—by hearsay or seizure. He repeatedly admits to having violently persecuted the church he so faithfully serves (1 Corinthians 15:9; Galatians 1:13; Philippians 3:6). Even Paul’s biggest booster, the author of Acts, introduces Paul to the reader as an accessory to a lynching (Acts 7:60).

So we may well ask: why should we take seriously, let alone read reverently, this vituperative, hallucinating, conflict-ridden polemicist who was at the same time both a passionate disciple of a man he never followed and a passionate enemy, by his own admission, of those who did? Why hasn’t the world written him off as a fulminating, apocalyptic crackpot? And why has a worldwide Christian communion been celebrating his birthday?

Because that man, in the perverse hindsight that only dogma could call Providence, became the future of an ancient movement of unlettered, agrarian, Semitic-speaking, indigenous Palestinians that would come to be co-opted by parvenus who, like him, were none of those things.

And because another man, now enthroned in the capital city of the empire Paul supposedly resisted, decided this was Paul’s year. And what a year it was.

Allen Dwight Callahan is the author of The Talking Book: African Americans and the Bible (Yale University Press) and A Love Supreme: A History of the Johannine Tradition (Fortress Press).