In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Mojave Cross

TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: If you ever wondered where the middle of nowhere really is, it just might be right here: the Mojave Preserve in southern California. At 1.6 million acres, it is vast. Some find it beautiful, some even sacred. Slightly more than 90 percent of the preserve is owned by the federal government and maintained by the National Park Service. In 1934, the Death Valley chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars put up a cross here to honor American soldiers who lost their lives in World War I. But the cross is now encased in a plywood box as a result of a lawsuit brought by Frank Buono, with the backing of the American Civil Liberties Union.

FRANK BUONO: I want the cross on every Catholic church. I want the cross in my home. But I don’t want the cross to be permanently placed on federal government public lands or any other public lands for that matter.

Frank Buono |

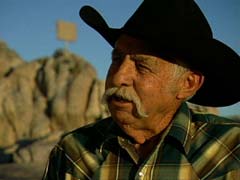

O’BRIEN: Seventy-year-old Henry Sandoz has been taking care of the cross for the last 26 years. His best friend, a World War I medic on his death bed had exacted a promise from Sandoz back in 1983 to do so.

(to Henry Sandoz): Why is it so important?

HENRY SANDOZ: Well, because of my word to my friend that I would maintain it. To me it means a whole lot.

O’BRIEN: Buono persuaded federal courts in California that the cross unconstitutionally promotes the Christian faith, a claim Henry Sandoz says he just doesn’t get.

HENRY SANDOZ: It shouldn’t mean no more than a memorial to the veterans, and also, when you see a cross on the highway you don’t necessarily—and I don’t either—think about that cross aspect, like you’re saying, well, somebody died there. That’s the meaning I think most people have out of it, or should have.

O’BRIEN: The US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, however, found putting the display on public land violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause, which prohibits the government from advancing religion. The decision outraged many veterans and triggered a public relations campaign on their behalf by the Dallas-based Liberty Legal Institute:

(Video produced by Liberty Legal Institute): “Our veterans stood for us. Now that their memorials are under attack around the country, are you willing to stand with them?”

O’BRIEN: Attorney Kelly Shackelford, who runs the Liberty Legal Institute, says the cross is all about honoring the nation’s war dead and has nothing to do with promoting religion:

KELL SHACKELFORD (Liberty Legal Institute): Well, I mean, if this cross goes down, because it’s a memorial in the middle of the desert, if you have to tear down a seven-foot cross in the middle of 1.6 million acres of desert, what do you have to do at Arlington Memorial Cemetery with a 24-foot-tall cross? This would literally affect almost every community in our country, because they all have veterans’ memorials, and a lot of those have religious imagery that’s attached to those.

O’BRIEN (to Frank Buono): What about Arlington National Cemetery?

FRANK BUONO: Oh, wonderful. You know, there’s probably no better place to express one’s religious beliefs than in a cemetery. This is not a cemetery.

Henry Sandoz |

O’BRIEN: At least on the surface Frank Buono, a transplanted New Yorker, would appear to be an unlikely plaintiff in such a case. He helped run the Mojave Preserve in the mid-nineties as an assistant superintendent, and he is a practicing Catholic. The walls of his home are lined with crucifixes and other religious symbols, and Buono rankles at the suggestion that the purpose of the Mojave cross is solely to remember the nation’s war dead.

FRANK BUONO: What really disturbs me is the argument that somehow the cross is a secular symbol. I can’t think of anything more offensive to a Christian, to a Catholic, that the cross is a secular symbol. They say, well, it’s a secular symbol of death and sacrifice, and I say, well, only to the extent that it symbolizes the death and sacrifices of Jesus Christ. That is why the cross is a symbol of death and sacrifice, and believe me, I think to a Muslim, to a Jew, to a Hindu, to a Buddhist the cross is no such symbol of death and sacrifice.

O’BRIEN: The furor, if not the rage, the case has generated has not been lost on Buono.

(to Frank Buono): We’ve seen interviews with the people in that little town.

BUONO: Yeah.

O’BRIEN: They want to string you up.

BUONO: Oh, I have been told, though I try to avoid the sites, that if you go on the Internet and put my name in you’ll get people saying incredible things about me. Even within my own family I’ve had some people say, what are you doing? This is the cross, you’re a Catholic, and what are you…

O’BRIEN: Buono’s case also got the attention of the U.S. Congress and Representative Jerry Lewis, whose 41st congressional district includes the Mojave Preserve. Lewis introduced legislation that would have transferred the land on which the cross was located to a private veterans group in hopes of circumventing the constitutional question the cross raised.

REP. JERRY LEWIS (R-Calif.): We’ve attempted by way of the amendments and the appropriations process to first allow there to be a property exchange. Because we were fighting a battle with endless lawyers of ACLU, it seemed to us it was important to set aside the question as early as possible to preserve the cross itself.

O’BRIEN: Lewis’s bill allowed the Interior Department to take the land back should the cross ever be removed, prompting the lower courts to find the transaction a “sham.” Buono has now moved away from the Mojave Preserve—almost 500 miles away—to a small town in Arizona not far from the Mexican border, so far away that the Interior Department says Buono no longer has a real stake in the case. The department has asked the Supreme Court to throw out Buono’s complaint because his only real injury is that “he must observe government conduct with which he disagrees.”

(to Frank Buono): What’s it to you? You live 500 miles away.

(to Frank Buono): What’s it to you? You live 500 miles away.

FRANK BUONO: Whether I’m 500 miles away or five feet away from it, the fact of the matter is that that land is land that I own, that’s land that you own; that’s federal public lands. It belongs to everyone, and so it matters to me that the lands that are held in common by the United States do not become the venues for sectarian religious expressions, even of my own religious expressions.

O’BRIEN: Legal scholars say this case has at least the potential to be the most important religion case to reach the Supreme Court in decades. But there have been many cases involving religious displays on public property. What makes this case so different may have less to do with the case itself than with the court that will decide it. The justices have long been sharply split on religion questions, often dividing 5-4. The addition of three new justices in the last four years could change everything. Erwin Chemerinsky is dean of the law school at the University of California at Irvine.

PROFESSOR ERWIN CHEMERINSKY: I think there are five votes on the current court that want to dramatically change the law with regard to the wall that separates church and state. These five justices—Roberts, Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas, Alito—don’t believe that there’s a wall that separates church and state.

O’BRIEN: No decision is likely from the High Court for several months in a case that could have momentous consequences for the country, notwithstanding its simple beginnings arising out of Henry Sandoz’s pledge to a dying friend 26 years ago.

HENRY SANDOZ: You know, to me—I guess it’s really great, but I’m just kind of a hick, I guess you’d say, a country person, and it’s really out of the ordinary for me.

O’BRIEN: The words “separation of church and state” do not appear anywhere in the Constitution. The First Amendment ban on government establishment of religion would surely require at least some separation—but how much? This reconstituted Supreme Court today appears poised to reconsider that crucial question.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Tim O’Brien in Washington.