In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Healing the Wounds of War

by Benedicta Cipolla

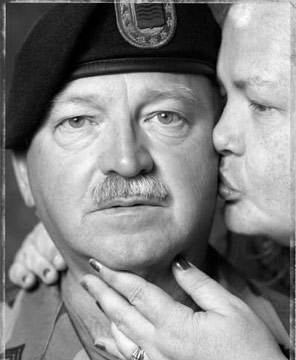

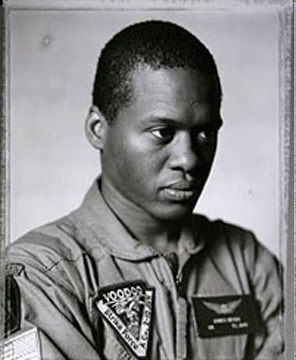

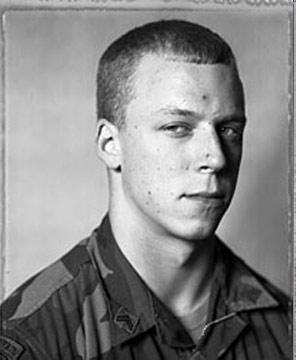

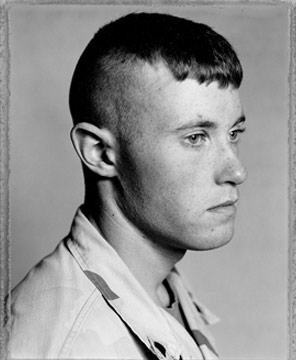

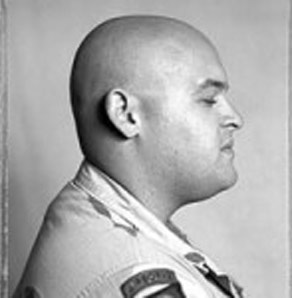

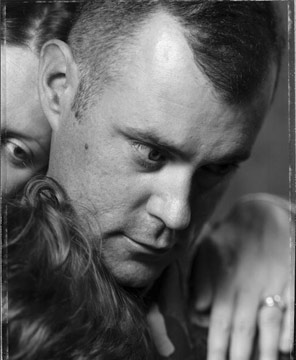

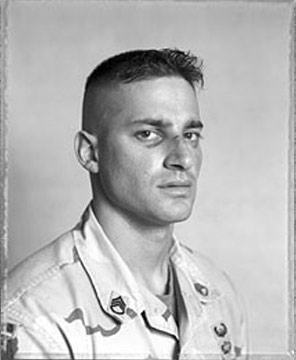

Photos by Suzanne Opton

Originally published November 30, 2007

War is, in some ways, the ultimate spiritual crisis.

By its very nature, it requires participants to perform acts that would be considered legally and morally wrong in civilian life. “Your whole life, regardless of religion, you’re told, ‘Don’t kill, don’t kill, don’t kill.’ Then all of a sudden it’s, ‘Here’s a gun.’ It’s hard to reconcile that,” says Linda McClenahan, a Dominican nun, trauma counselor, and former Vietnam Army sergeant who lives in Racine, Wisconsin.

In a 1995 study, 51 percent of veterans in residential post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment in a Veterans Affairs facility said they had abandoned their religious faith during the war in which they fought. In the same study, 74 percent of respondents said they had difficulty reconciling their religious beliefs with traumatic war-zone events. Battle creates moral confusion, and it can leave a soldier spiritually as well as physically wounded.

Unlike many other traumatic experiences, combat can cause “moral pain” arising from “the realization that one has committed acts with real and terrible consequences,” according to a seminal 1981 article in PSYCHOLOGY TODAY by Peter Marin. He was writing about Vietnam, but his overarching thesis could be applied to any military conflict. Profound moral distress is the “real horror” of war, yet its effect on those who fight is rarely discussed.

The difficulty of talking about the spiritual wounds of war was apparent in October when the Episcopal Society of St. John the Evangelist in Cambridge, Mass., announced a four-day retreat at its monastery called “Binding Up Our Wounds,” for men and women returning from places of war. Nobody showed up.

A November report published in the Journal of the American Medical Association underscores the magnitude of the problem. After they return from combat in Iraq, one-in-five active-duty soldiers need mental health care. For reservists, the numbers were even higher: Two out of five need treatment. And one 2004 study concluded that veterans who avail themselves of mental health services appear to be driven more by guilt and the weakening of their religious faith than by the severity of their PTSD symptoms.

“In a war, in a firefight, you’re both victim and perpetrator at the same time,” says the Rev. Alan Cutter, general presbyter of southern Louisiana for the Presbyterian Church (USA) and a former Navy officer who served in Vietnam. “At its heart, a trauma, and especially a war trauma, leaves a wound to the human spirit. When I came back, my spirit was pretty well shredded and ripped.”

Marin wrote that moral pain or guilt erroneously remained a form of psychological neurosis or pathological symptom, “something to escape rather than learn from,” and he alleged that therapy failed to take moral experience into account. More than a quarter-century later, many experts feel little has changed.

“Once the category of PTSD was established in the early ’80s, that swallowed the veteran whole,” says William Mahedy, an Episcopal priest and former Army chaplain who has spent 33 years working with veterans in southern California. “Combat creates far more wide-ranging problems than stress.”

It’s not just the act of taking a life that raises the kinds of questions Mahedy says can only be addressed spiritually and philosophically. Witnessing death and suffering also goes to the heart of life’s meaning: Why did God, if there is a God, allow this? Why is killing the enemy not a sin? How can I be forgiven? Why couldn’t I save my comrade? Why am I alive when I don’t deserve to be? Psychology isn’t always equipped to answer such questions.

“Trauma can be characterized as a sense of betrayal of one’s experiences: life wasn’t supposed to be this way,” says the Rev. Jackson Day, an Army chaplain in the central highlands of Vietnam from 1968 to 1969 and now the pastor of Grace United Methodist Church in Upperco, Maryland. “The faith parallel to that would be the statement, ‘God has let me down. I did my part, and God didn’t do his.'”

In his book ACHILLES IN VIETNAM (1995), clinical psychiatrist Jonathan Shay explored combat trauma through a close reading of the ancient text of the Iliad and his own experiences treating Vietnam veterans with chronic PTSD. Those with lifelong psychological injury, he argued, had suffered a betrayal of “what’s right” — of leadership, trust, the dead, the social and moral order — above and beyond war’s “usual” horror and grief. Those whose belief in God’s love was shattered by war suffered another betrayal: their worldview and sense of virtue were obliterated.

In Shay’s follow-up book, ODYSSEUS IN AMERICA (2002), he used Homer’s Odyssey to look at returning troops whose spiritual wounds incurred on the battlefield can fester and worsen at home. The conviction that virtue is no longer possible, given God’s abandonment, can result in a withdrawal from moral commitment.

Medical-psychological therapies, Shay wrote, “are not, and should not be, the only therapies available for moral pain. Religious and cultural therapies are not only possible, but may well be superior to what mental health professionals conventionally offer.”

In an interview, Shay, whose work at the Boston VA outpatient clinic has been primarily with Roman Catholic patients, elaborated. “My sense is that this is a fundamentally religious issue. It’s possible to package it as a mental health issue, but I think we lose out. Even people who have had good secular treatments for their trauma still feel a need for the religious dimension of it. I don’t think as a society we’re offering it.”

VA research suggests that veterans who have suffered a greater loss of meaning to their lives are more likely to seek help from both clergy and mental health professionals. Therapists, however, may hit a roadblock with treatment when they feel out of their depth on spiritual or religious matters, and most clergy are not trained in trauma response.

But all faith traditions offer resources to respond to trauma, such as the Catholic sacrament of penance and reconciliation, of which confession is a part.

One of Shay’s patients was ordered by his lieutenant to “take care of” 17 Viet Cong prisoners, an order he interpreted as “kill them.” His squad was reluctant, and so he began firing first, even egging the others on. What weighed most heavily on his conscience years later was not his crime, but his belief that he had led others into mortal sin. “My response was that we knew a number of priests who had been chaplains in war and who knew what this was about,” Shay says. “This is about the real stuff, not the sins you confessed to in parochial school, but murder, cruelty, rape. [Your faith] has the resources to respond to that in a way that will matter to you.”

What matters to one won’t always matter to another. It depends on what faith, ritual, sacrament, or person you have invested authority in, says Rabbi Harold Robinson, a retired Navy rear admiral and the current director of the JWB [Jewish Welfare Board] Jewish Chaplains Council. As a chaplain, Robinson found that the study of Jewish texts on war and self-defense served as a powerful resource in addressing spiritual injury. “I think you invest more of yourself when you try to study and understand something,” he says. “By grappling with the text you’re also grappling with yourself. It’s an interactive process, not one that’s just imposed.”

Other chaplains have used Psalm 23, which famously portrays God as a patient shepherd, or Psalm 31, whose speaker calls himself a “broken vessel,” and they ask where veterans see themselves in the psalm. Even people who are not religious might be open to the psalms, according to Major Samuel Godfrey, an ordained minister in the Pentecostal Holiness Church and a chaplain in Iraq for the Combat Aviation Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division. Shareda Hosein, an Army Reserve lieutenant colonel and the Muslim chaplain at Tufts University, lists several passages from the Qur’an dealing with Allah’s forgiveness and guidance that she says she might use in counseling a Muslim soldier — from Sura 39, for example, which promises mercy for those who repent: “Say: ‘My servants who have transgressed against themselves! Despair not of the Mercy of Allah, verily Allah forgives all sins. Truly, He is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful.'”

In early medieval Europe, warriors returning from battle were expected to feel shame, even when their killing was technically licit. A 9th-century penitential, according to THE MORAL TREATMENT OF WARRIORS IN EARLY MEDIEVAL AND MODERN TIMES by Bernard Verkamp, “stipulates that the man who is blameless in committing homicide in war should nonetheless seek purification, because of the shedding of blood, and stay away from the church for one or two weeks, and abstain from meat and drink during the period.”

For the ancient Hebrews, too, the shedding of blood was considered a source of contamination. The Book of Numbers dictated a seven-day period of segregation outside the camp for returning warriors and mandated the purification of fighters and their garments.

As founder of the International Conference of War Veteran Ministers, Father Phil Salois, a Catholic priest and chief of chaplain services for the VA Boston Healthcare System, has developed ecumenical liturgies incorporating verse by World War I poet and soldier Wilfred Owen, Bible readings, and prayers written specifically for services of reconciliation and healing. “I think it’s about redemption, to bring back meaning in their lives,” says Salois, who served as an infantry soldier in Vietnam. “We try to teach them God loves them no matter what happened to them. There is nothing that is unredeemable.”

Some Jewish veterans use the mikveh, or ritual bath, in their search for a rite of purification and rebirth. The Birkat Hagomel, a public prayer of thanksgiving (“Praised art thou O eternal God ruler of the universe, who has redeemed with kindnesses those who are guilty, and who has redeemed me with all manner of goodness”), can also be recited before a Jewish congregation by someone who has survived a life-threatening situation. The prayer requires a communal response affirming redemption. “Afterwards, it entitles everybody in the congregation to go up to you and say what happened to you? Are you OK? And to make human contact out of that moment,” says Rabbi Robinson.

But Robinson questions whether a truly communal purification ritual is possible, suggesting that the separation between those who serve in the military and those who don’t is too wide to bridge meaningfully, and there is no consensus about where purification finally resides. Is it with the doctor and the psychiatrist, or with the priest and the rabbi?

Yet community involvement is something Shay feels is crucial to the whole notion of a purification ritual. “It’s not a matter of pointing a finger at the returning vet,” he says. “It’s that we all need purification after battle. You have gone into danger and done some things that perhaps were truly terrible, but you’ve done them in our name, and it’s we who sent you to do those things.”

Some returning veterans experience great feelings of isolation, and communal rituals can offset their sense of aloneness and provide them with an opportunity to talk about their experiences. As Captain Jeffrey Cox, a Massachusetts National Guard social worker who returned from a tour of duty in Iraq in 2006, puts it, “Does anyone…know my story outside of the people I’ve served with?”

As the recent experience of the Episcopal monastery in Cambridge demonstrates, for those who have served — and will serve — in Iraq and Afghanistan, it may be a long time before anyone hears their stories. Salois recalls a Chicago retreat where four couples canceled the day it began. That was the first retreat a young Iraq veteran had attended. “He was very focused on what we said about our experiences [in Vietnam] and how we journeyed throughout the years. When it came time for him to speak, he said, ‘I appreciate everything you’ve said, but I’m not ready to talk about it.’ And I thought, well, it was 13 years before I started talking about this.”

“One can hope that the rest of us will accompany them when we can and follow them when we should,” Peter Marin wrote of the nation’s war veterans. Their recovery, we may need to learn again, is a collective responsibility.

Benedicta Cipolla, a writer in New York City, has also written for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on Iraq, the ethics of torture, and Reinhold Niebuhr.