In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Juvenile Sentencing

Originally broadcast January 30, 2009

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: This past week (November 9) the Supreme Court heard arguments about whether it’s constitutional to sentence juveniles who commit crimes other than murder to life in prison without parole. Tim O’Brien reports.

TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: Twenty-three-year-old Kenneth Young had just turned 15 when he committed a string of hotel robberies in the Tampa area, acting at the direction of 25-year-old Jacques Bethea, a neighborhood drug dealer with a long arrest record. Bethea would hold the gun. Young would take the money.

KENNETH YOUNG: The only thing he told me to do was get the money and the tapes, and that was it.

O’BRIEN: What tapes?

YOUNG: Like video tapes from the video cameras.

O’BRIEN: The security camera?

YOUNG: Yes, sir.

YOUNG: Yes, sir.

O’BRIEN: And you did that?

YOUNG: Yes, sir.

O’BRIEN: Young says he had little choice. His mother was addicted to crack cocaine and had stolen drugs from Bethea. He believed her life was in danger.

YOUNG: He threatened to hurt my Momma.

O’BRIEN: What did he say he’d do?

YOUNG: Kill her.

O’BRIEN: If you didn’t go along.

YOUNG: Yes, sir.

O’BRIEN: Young’s mother blames herself for her son’s problems.

STEPHANIE YOUNG: Yes, I do, I do, because if it wasn’t for the drugs, I mean …

O’BRIEN: But that didn’t keep Kenneth from being sentenced to life in prison with no parole.

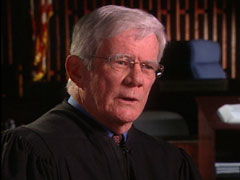

JUDGE J. ROGERS PADGETT: What we see is what we get in the way of a defendant. We get a person who shows no remorse. We get a person who is smiling in court, thinks it’s funny. We have a person who, while he is under consideration for a life sentence, is flipping signals to people in the gallery.

Judge J. Rogers Padgett |

O’BRIEN: He’s only 15, barely.

PADGETT: We have a person who gives no appearance of deserving any slack whatsoever and sentence him, so we give him a life sentence.

O’BRIEN: Florida, like many states, allows prosecutors to charge juveniles as adults for serious crimes, and the state legislature did away with all parole in 1995. As a result, there are now 77 inmates in the state serving life without parole for non-homicides committed when they were under 18, more than in all other states combined. Paolo Annino runs the Children in Prison Project at Florida State University:

PAOLO ANNINO: This is no different from slavery or other major moral issues. Placing children in adult prisons for life is a death sentence for children. Do we want to do that as a society? Do we want to ignore our Western traditions?

O’BRIEN: This week (November 9) the U.S. Supreme Court took up that question in two separate cases involving Terrence Graham, who at age 17 committed armed burglaries while on parole for a previous armed robbery, and Joe Sullivan, who was convicted of raping and robbing a 72-year-old woman when he was only 13.

BRYAN STEVENSON: We don’t think there’s any dispute that sentencing a 13-year-old to life in prison without parole is unusual. It’s happened only twice for non-homicides. We also think that to say to any child of 13 that you’re only fit to die in prison is cruel.

O’BRIEN: But Stevenson ran into some skeptical justices, including Antonin Scalia: “I don’t see why it is any crueler to an adolescent that it is to an adult… Where do you draw the line?” Justice Sam Alito: “What about …brutal rapes, assaults that render the victim paraplegic but not dead …the person shows no remorse… the worst case you could possibly imagine? That person must at some point be made eligible for parole? “You are correct, your honor,” answered Brian Gowdy, the attorney for Terrence Graham.

Brian Gowdy |

BRIAN GOWDY: If the court rules in Terrence’s favor, about one hundred persons who committed crimes as adolescents will benefit by getting a chance to show some day that they have changed, and that’s all we’re asking for. Not for immediate release, but a chance to show that the kid has changed.

O’BRIEN: In court, Gowdy pointed to a landmark Supreme Court ruling four years ago in which the justices rejected the death penalty for juvenile offenders, relying heavily on evidence showing that juveniles use a different part of the brain in the decision-making process, making them more likely to act irrationally, less likely to appreciate the consequences of what they do. Several justices observed that that was a death penalty case, and death is different.

GOWDY: Death is different, but not in any critical respects when you’re talking about an adolescent. Both sentences condemn the adolescent to die in prison, both give up on the kid, both determine that the adolescent can’t be changed, and both say that, based on an adolescent mistake, you can never live in civil society.

O’BRIEN: The attorney for Florida said the state’s sentencing practices were aimed at addressing a serious crime problem and that such policy decisions should not be second-guessed by federal judges.

SCOTT MAKAR (Florida Solicitor General): That’s a quintessential states’ judgment, and 21 states have said no to parole and our position is that the court shouldn’t impose something on the states that the states themselves have rejected.

O’BRIEN: Chief Justice John Roberts proposed a compromise requiring judges and juries to consider a defendant’s youth, but allowing life without parole in extreme cases. Defense lawyers dismissed the idea as too little.

O’BRIEN: Chief Justice John Roberts proposed a compromise requiring judges and juries to consider a defendant’s youth, but allowing life without parole in extreme cases. Defense lawyers dismissed the idea as too little.

STEVENSON: Because poor kids and minority kids and disadvantaged kids are always the ones who end up with these harsh sentence.

O’BRIEN: Conservatives on the court dismissed it as too much. Meanwhile, back in Florida, Kenneth Young and more than a hundred other prison inmates nationwide serving life without parole for crimes they committed as children got some support from what might seem to be an unlikely source. The judge who sentenced Young, J. Rogers Padgett, has come out against laws that deny parole to juveniles in non-homicide cases.

PADGETT: If I went and talked to Kenneth, I might have sympathy, too, because I firmly believe the Department of Corrections ought to be given the latitude to determine when these people are ready to go. What do I know? At the time of sentencing I’m doing a snapshot, so what do I know?

O’BRIEN: The justices appeared sharply divided, making any decision unlikely before the end of the term next June. For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Tim O’Brien in Washington.

ABERNETHY: Among those who have filed briefs with the court are 20 religious groups that argued that the values of mercy, forgiveness, and compassion are central to their faiths. They said judges have a responsibility to consider those values, along with the possibility of rehabilitation, especially for juveniles. They urged what they call “restorative justice.”