Judaism: A Way of Being

BOOK REVIEW

Seeing Judaism

by Juliana Ochs

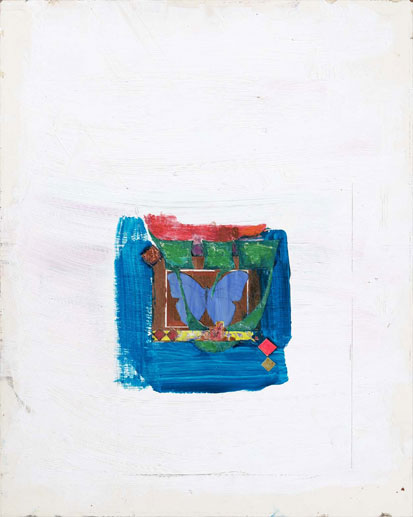

Click here to view a gallery of paintings by David Gelernter.

At the core of personal trauma there is often a loss of faith in life’s order and stability. When faced with a crisis, some people turn to religion. Others turn to artistic expression. David Gelernter turned to both, and his new book Judaism: A Way of Being (Yale University Press, 2009) displays a unique entwining of the two.

Gelernter is a professor of computer science at Yale University whose scientific mind has long looked toward the future, some say predicted it. The “tuple spaces” paradigm for parallel distributed computing that he introduced in the 1980s became the basis of many computer communication and programming systems. His book Mirror Worlds (Oxford University Press, 1991) is said to have foreseen the Internet and inspired the programming language Java.

In June 1993, while going through a stack of mail in his Yale office, Gelernter opened a package he believed was a doctoral dissertation. Smoke billowed out and the package exploded. It was a mail bomb sent by Ted Kaczynski, the man the FBI dubbed the Unabomber, and it permanently damaged Gelernter’s right hand and eye.

Gelernter recovered from his injuries but emerged an impassioned conservative critic of American life and politics. In recent years, he has traced America’s moral decline to a class of intellectuals he says came to the fore as the country’s new elite in the 1960s, hijacked cultural discourse, and corrupted social values.

If the bombing prompted political polemic, it also drew Gelernter closer to religion. This is not to say he was new to Judaism. David Hillel Gelernter, the grandson of a rabbi, grew up a Reform Jew. Before he decided on computer science he received a master’s degree in Hebrew Bible. The Orthodox Judaism he has turned to more recently, however, and that he celebrates in his new book is the one he sees as pure and authentic, the kind of religion capable of drawing the world back into secure order. It is Judaism without the complexity introduced by gender equality and other modern revolutions. Gelernter presents himself as a local guide to the faith, offering to lead Jewish and non-Jewish readers alike into what he calls “the inner courtyard” of Judaism to see what cannot be seen from the outside. His book, he claims, is “Judaism at full strength, straight up; no water, no soda, aged in oak for three thousand years.”

If the bombing prompted political polemic, it also drew Gelernter closer to religion. This is not to say he was new to Judaism. David Hillel Gelernter, the grandson of a rabbi, grew up a Reform Jew. Before he decided on computer science he received a master’s degree in Hebrew Bible. The Orthodox Judaism he has turned to more recently, however, and that he celebrates in his new book is the one he sees as pure and authentic, the kind of religion capable of drawing the world back into secure order. It is Judaism without the complexity introduced by gender equality and other modern revolutions. Gelernter presents himself as a local guide to the faith, offering to lead Jewish and non-Jewish readers alike into what he calls “the inner courtyard” of Judaism to see what cannot be seen from the outside. His book, he claims, is “Judaism at full strength, straight up; no water, no soda, aged in oak for three thousand years.”

For Gelernter, to understand Judaism you must see it. Far from being allergic to images, Judaism is a religious tradition passionate about the beauty and aesthetics of life. The Hebrew Bible is itself pictorial, with stories and lessons conveyed through vivid imagery, from the dove with an olive branch in its beak to the Burning Bush. “Judaism,” Gelernter writes, “tells Jews what is right—and adorns the bare thread of human life with sanctity, jewel-by-jewel, until a Jewish life glows with soft color: warm amber and silver, cool fragrant yellow and glowing orange and translucent purple-rose.”

Gelernter is an artist, after all, and considers painting the oldest strand of his personal history. He took art lessons as a child, and as a teenager living on Long Island traveled regularly to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan to copy Degas in pencil and charcoal. When he lost function in his right hand after the bombing, what worried him most was his ability to continue painting. Slowly, Gelernter learned to use his left hand the way he once used his right, and so painting has remained central to his identity and intellect.

Images are also central to his book, structured around four “image-themes” (separation, veil, perfect asymmetry, and inward pilgrimage) that outline the codes and aesthetics of what Gelernter says is a “common Judaism.” “My basic themes take the form of images,” he explains, “because Judaism is less a system of belief than a way of living, a particular texture of time.” Each theme conveys one central facet of Judaism and also serves as a microcosm of the religion as a whole.

The idea of separation refers to man’s struggle to transcend nature and create himself in God’s image. Many biblical images convey the essence of separation, such as the parting of the Red Sea, the waters forced apart at Creation, and the Torah scroll held wide and open in front of a synagogue congregation (a ritual called hagba). Separation, Gelernter explains, guides halakha, the set of Jewish laws that dictate religious practices and beliefs, as well as numerous aspects of daily life. Keeping kosher and setting the Sabbath apart from the work week as a day of rest are acts of separation that Jews are obliged to live by. These practices, says Gelernter, turn everyday life into a continuous process of sanctification.

The image-theme he calls “veil” conveys the principle that while one cannot see or know God, one can comprehend God’s inconceivablessness, symbolized by a sacred veil. Images of the veil in Judaism include Moses veiling his face at Mount Sinai after meeting with God, a prayer shawl or tallit draped over a person at prayer, the curtain hanging in front of the Holy Ark in a synagogue, and the mezuzah that encloses a small scroll of biblical text. These images, Gelernter suggests, can help us grasp the deeper and more elusive question of how man can engage with a transcendent, ineffable God.

There are those who will disagree with many of the views that run through Gelernter’s book, such as his claims that Judaism is the most important intellectual development in Western history; that God has withdrawn from the modern world; that Reform and Conservative Judaism do not work; and that the purpose of life is to marry and rear a family. In a chapter on his third theme, “perfect asymmetry,” on the importance of marriage and the family, Gelernter is not subtle about his social critique. He argues that the feminist effort for male and female equality “is an act of aggression against both sanctity and humanity.”

Aspects of the text are indeed narrow and partial, but the image-themes still allow for more expansive thinking. With the theme of “inward pilgrimage” Gelernter broaches the problem of how to reconcile a just God with the reality of a cruel world. Judaism tells us that lo bashamayim hi, “the Torah is not in heaven”; it must be interpreted and applied on earth. According to Gelernter, interrogation of the world around us and inner doubt are equal parts of the Jewish journey.

Eight glossy reproductions of paintings by Gelernter are tucked inside the book, products of his own journey. They are not illustrations of the image-themes, but rather colorful and delicate ornamentations of Jewish text, coming out of a tradition of illuminated manuscripts. Gelernter works with acrylic, collage, and gold leaf. Butterflies are a recurring motif. In one painting, the Hebrew phrase Ha’Mavdil bein kodesh l’chol, “Who separates between the sacred and the ordinary,” is enhanced with orange and magenta and bejeweled with a golden butterfly that helps form one of the letters. Marking the transition between sacred and secular time, this blessing is recited while holding a flickering candle at the end of the Sabbath. Gelernter’s artwork sanctifies the blessing, just as the thematic image of separation sanctifies life.

The indigo, cerulean, and crimson butterflies embedded in his paintings exemplify the delight that, for Gelernter, gives meaning to religious life. “Judaism is above all a religion of joy,” he asserts repeatedly throughout the book. At the center of “the vast, intricate, beautiful palace that is Judaism,” he writes, is “a thread of ecstasy…the whole word, space and time and suffering and all, pulled together by triumphant jubilation.”

The Judaism Gelernter lays out in Judaism may not be triumphant for everyone. While he claims to present the “whole” of Jewish life, some may find that a Judaism devoid of contemporary innovations lacks the interpretive essence so central to the religion. But Gelernter’s idea of image-themes and his own paintings succeed in areas where his text might not. They give permission to those who practice Judaism and those who study it to seek meaning and connection to the tradition not only through text but also through images, aesthetics, the senses, and the soft “glow” of color.

Juliana Ochs has written most recently for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on “Painting a Jewish Memory Book” and “The Story of the Hebrew Book.”