Mark Toulouse: The Ironic Rhetoric of a New President

Using every syllable of his considerable rhetorical ability in his first State of the Union address, President Obama laid it on the line for a nation filled with skepticism. In some moments, he spoke with contrition about “political setbacks,” some of which “were deserved.” After speaking of massive, unheard of government financial deficits, he spoke openly of the growing “deficit of trust” in government and its leaders. He admitted the growing doubt in the country that he can “deliver” on his promise of “change” Americans can “believe in.” But he also told Americans how “hopeful” he was about the future.

With skill he reminded hearers, ever so subtly, about the mess he inherited. He spoke of solutions, some already in place, others in process, still others being frustrated by Republican insistence “that sixty votes in the Senate are required to do any business at all in this town.” Perhaps in an appeal to regain lost support among independent voters and, at the same time, connect with those on “Main Street,” Obama clearly named some villains accountable for many of the country’s problems: those responsible for the “bad behaviour on Wall Street,” the politicians who “obstruct every single bill just because they can,” the “outsized influence of lobbyists,” the “banks that helped cause this crisis,” and “insurance company abuses.” He outlined steps for reform in all these circles of influence. He renewed his vows to end the war in Iraq, increase effectiveness in Afghanistan, and multiply sanctions in North Korea and Iran if they continue to pursue nuclear prowess. His speech hit most of the right notes on terrorism, thankfully without the civil and religious piety too often found in the rhetoric of President Bush.

But one aspect of his populist rhetoric really left me cold—gave me a chill, in fact. Though I don’t think my response has anything to do with my living in Canada these days, I’m confident my friends and colleagues here would conclude Obama’s words were just “more of the same” from the neighboring empire to the south. I must admit to being profoundly disappointed precisely because I still believe in the change he has promoted. While near the end of his speech he spoke of advancing “the common security and prosperity of all people” in order “to sustain a global recovery,” the heart of this address shouted “We’re Number One!

I applaud Obama’s concern for both “energy efficiency and clean energy,” but his argument that the “nation that leads the clean energy economy will be the nation that leads the global economy“ and that “America must be that nation” places “greening” at the service of a greedy desire to retain (regain?) control of the world’s resources. What has American leadership of the global economy done for the world? What had it accomplished in Haiti prior to this devastating earthquake, for example? Studies like the one done by the World Institute for Development Economics Research at United Nations University indicate that the bottom 50 percent of the world’s adults own around one percent of global wealth, while the world’s richest one percent of adults owned approximately 40 percent of the world’s resources. Or, as economist Branko Milanovic of the World Bank put it in 2002, “The top 10 percent of the US population has an aggregate income equal to income of the poorest 43 percent of people in the world.” Yes, by all means, let’s keep that going.

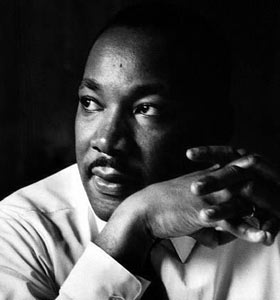

It is doubly ironic that the core of the first State of the Union address from a black president would contain such a profoundly affirmative nod in the direction of good old US economic imperialism—doubly ironic because, first, the history of slavery and racism is definitely connected to such classic American economic hubris, and, second, he made this particular case so clearly dependent on the rhetoric of Martin Luther King. “How long should we wait?” Obama asked. “How long should America put its future on hold? … Well, I do not accept second place for the United States of America….It’s time to get serious about fixing the problems that are hampering our growth.”

It is doubly ironic that the core of the first State of the Union address from a black president would contain such a profoundly affirmative nod in the direction of good old US economic imperialism—doubly ironic because, first, the history of slavery and racism is definitely connected to such classic American economic hubris, and, second, he made this particular case so clearly dependent on the rhetoric of Martin Luther King. “How long should we wait?” Obama asked. “How long should America put its future on hold? … Well, I do not accept second place for the United States of America….It’s time to get serious about fixing the problems that are hampering our growth.”

Set over against Obama’s rhetorical lament, I prefer King’s use of it in 1965 in Montgomery: “How long will it take? … How long will justice be crucified?” As he put it in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, “justice too long delayed is justice denied.” Or perhaps Isaiah’s lament fits the irony better if the US continues on its path of economic domination: “For how long, O Lord? And [God] said: ‘Until cities lie waste without inhabitant, and houses without people, and the land is utterly desolate.’”

Mark G. Toulouse is principal and professor of the history of Christianity at Emmanuel College of Victoria University in the University of Toronto.