In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Lincoln Electric

JOHN STROPKI (CEO, Lincoln Electric): Welding builds America. I mean, what’s interesting is if you look around the slides and you see the various different industries…

PHIL JONES, correspondent: Lincoln Electric is the world’s leading developer and manufacturer of arc-welding equipment. It has rigorous performance standards. There is mandatory overtime, no unions, and virtually no paid sick days. So why would anyone want to work here?

JONES: What’s the biggest bonus you ever got at the end of the year?

CURT BALK (Employee, Lincoln Electric): I guess I could tell you. Gross? Gross bonus?

CURT BALK (Employee, Lincoln Electric): I guess I could tell you. Gross? Gross bonus?

JONES: Yeah.

BALK: Probably my biggest was about $28,000.

ROB FULMER (Employee, Lincoln Electric): I don’t know all their ins and outs, but I know this: I feel solid and confident that this place will be here, and that I’m going to have a job ’til I retire.

JONES: That is because Lincoln’s employees don’t have to worry about this happening to them:

Movie clip from “Up in the Air”:

You and I are sitting here today because this will be your last week of your employment at this company.

Why me?

What am I supposed to do now?

Am I supposed to feel better that I’m not the only one losing my job?

This is ridiculous! I have been a fine employee for over 10 years, and this is the way you treat me?

Frank Koller, author of Spark |

FRANK KOLLER (Author of Spark: How Old-Fashioned Values Drive a Twenty-First Century Corporation): Over the past 20-30 years we’ve come to understand how horribly destructive layoffs are for the workers involved, for their families, and for the communities at large.

JONES: Journalist Frank Koller has written a book about Lincoln Electric’s unusual management tradition.

KOLLER: Lincoln believes that it is not only possible to protect people as well as profits, but that in fact over the long term the best way to protect your profits is to protect people.

STROPKI: When somebody loses their job, and they’re sitting at home every day, I think they lose a good part of their dignity that’s associated with that. In our system they come to work every day. Maybe they go home a little bit earlier, or maybe their paychecks are a little bit less, but they don’t lose their dignity.

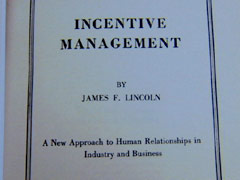

JONES: In 1895, after being laid off from his manufacturing job, John Lincoln decided to start his own company. He later brought in his brother James to manage things. When the Depression hit, Lincoln Electric suffered along with everyone else. Desperate to keep their jobs, workers went to James with this proposal:

KOLLER: If we promise to work harder, and we in fact can improve the productivity of the company, will you share the benefits at the end of the year with us in a fair manner? And James Lincoln, actually, directly said yes.

JONES: The profit-sharing, which began in 1934, has continued to this day. The Lincoln brothers were encouraged to have high moral standards by their father, an itinerant minister.

DONALD HASTINGS (Former CEO, Lincoln Electric): He preached so much the Sermon on the Mount and the Golden Rule of doing unto others as you would have them do unto you.

DONALD HASTINGS (Former CEO, Lincoln Electric): He preached so much the Sermon on the Mount and the Golden Rule of doing unto others as you would have them do unto you.

JONES: Over his career, J.F., as he was known, wrote frequently of his moral principles: “If we follow the philosophy of Christ…we shall have the proper answer to the problem of lay-offs. When we treat the worker as we would like to be treated, the answer is plain. Continuous employment is needed to secure the cooperation of the worker. It is also basically sound.”

STROPKI: The thing that I always talk about, and we’ve used this term before, is this brain drain that comes when you just let people go. We keep this young talent that we’ve worked so hard to bring into the organization. They know we’re not going to desert them in the bad cycle, and they become more and more committed as far as the company is concerned.

JONES: Under the guaranteed employment policy, no one at Lincoln has been laid off for economic reasons for more than 60 years.

STROPKI: If you are a full-time employee for three consecutive years, the company will guarantee you 75 percent of a normal work week of work and compensation in good times or bad.

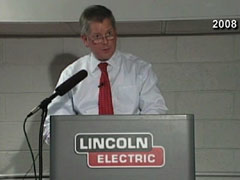

JONES: In 2008, business was especially good. The company paid out the highest bonuses in its history, more than $28,000 per employee.

STROPKI (speaking to employees): Congratulations, you earned it.

STROPKI (speaking to employees): Congratulations, you earned it.

JONES: But there was a warning.

STROPKI: I referred to comments that J.F. Lincoln had made when the bonus system started and cautioned people that 2009 would be a difficult year and be sure that they took a good portion of their bonus home and saved it for the rainy day that we knew was coming.

JONES: In 2009, those hard times hit. To survive, Lincoln reduced the work week from about 50 hours to 32. Some people were moved to jobs that paid less money, and there was an across-the-board salary cut. Also: a voluntary retirement plan. About 300 accepted, 10 percent of the work force. At the end of a very difficult year, Lincoln had ended up with a profit, and employees got bonuses averaging $17,000. But part of what determines those bonuses is the company policy of—with few exceptions—no paid sick days.

STROPKI: Look, you’re being paid when you’re working, and the company is successful when you’re working, not when you’re home. And it’s—with the bonus system, the way it’s structured, it’s difficult for an equal sharing of the bonus if you don’t have equal participation on the part of the workers.

JONES: Workers don’t get a paycheck just for showing up. Through a complicated merit system, employees know whether they’re performing up to standards. If they’re not, and if they’ve been at Lincoln less than three years, they can be terminated.

John Stropki, Lincoln Electric CEO |

STROPKI: We separated the high performers from the low performers. We began to meet with the low performers, let them know what we needed them to do in order for them to survive the crises that were coming, and those that reacted positively made it, and those that didn’t were let go based on performance standards.

JONES: The concept of pay based on quality piecework was started by James Lincoln in 1914. At other companies, piecework has been controversial, but not here.

(speaking to Lincoln Electric employee Curt Balk): Are you a top producer here?

BALK: I think so.

JONES: Why do you like to be on piecework?

BALK: It’s the incentive of knowing that I’m doing the job, and I get paid at the end of the day for what I’ve done, and to make a quality part.

JONES: Why do you like to work under piecework?

Roger Dubose |

ROGER DUBOSE: Piecework—it gives you a chance to—you’re not limited. Your hands are not tied. You’re not limited on the amount of earnings you can make.

JONES: No union?

STROPKI: No union in this factory. There’s never been a union in our Cleveland company.

JONES: And why is that?

STROPKI: I think because people feel they’ve been treated fairly and they’ve had it every bit as good or better opportunity than any union opportunity could provide them.

JONES: Another Lincoln policy—creation of an advisory board made up of representatives from all departments. It meets with management every two to three weeks, and any employee can have one-on-one access to the CEO just by making an appointment.

STROPKI: I have a picture of J.F. Lincoln up over my desk, and when I see that picture when I walk in the morning I recognize a responsibility to kind of adhere to the ideals of which he set out to run this company by.

KOLLER: Lincoln is successful by any metric that you can use on Wall Street. The stock does well over the long term. The company’s made a profit from every year from 1934. So there’s no question that in the business world Lincoln Electric is a success. The difference is that Lincoln Electric is also a success by any other measure that most of us, as ordinary people, would see as the right thing for a company to do.

JONES: So why aren’t more companies emulating Lincoln Electric? One reason: Lincoln policies are viewed, in business schools and on Wall Street, as inefficient.

JONES: So why aren’t more companies emulating Lincoln Electric? One reason: Lincoln policies are viewed, in business schools and on Wall Street, as inefficient.

KOLLER: Certainly on Wall Street the perception is that any kind of a guarantee for workers of any kind is a direct threat for shareholders.

JONES: Lincoln Electric does not presume to be a model for other companies, saying simply “this is what works for us, but it’s not easy.”

STROPKI: Companies have three stakeholders. They have their customers, they have their employees, and they have their shareholders. And which of those three stakeholders don’t want to be treated fairly? Treat people fairly. Treat people like you’d like to be treated.

JONES: The Golden Rule?

STROPKI: The Golden Rule.

JONES: Instead of laying people off in the current recession, Lincoln reassigned some of them to product development. As a result, the company has brought out more than one hundred new products. As one former CEO puts it, “When things pick up, I wouldn’t want to be a competitor of Lincoln Electric.”

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Phil Jones in Cleveland, Ohio.