An Unconventional History of Human Rights

by David E. Anderson

On December 10, the Nobel Peace Prize is scheduled to be presented to Chinese dissident and pro-democracy activist Liu Xiaobo.

Liu will not be in Oslo to accept the award. He’s languishing in a Chinese prison under an 11-year sentence. Nor, in all likelihood, will his wife go to Oslo to receive the prize for him. She has been under house arrest since October 8, when the Nobel committee named Liu as the recipient of this year’s award.

Fifteen Nobel peace laureates, including retired Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, former US President Jimmy Carter, and the Dalai Lama, urged the G20 group of nations to press China at their November meeting to free Liu. The appeal fell on deaf ears, as did a similar request from President Obama, last year’s peace laureate.

The Liu episode underscores in dramatic fashion both the ubiquity of human rights in international affairs and the constraints on a movement in which nation-state sovereignty and national foreign policy interests still dominate world events.

In a provocative and contrarian new book, “The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History” (Harvard University Press, 2010), Columbia University professor Samuel Moyn outlines the moral and political dilemmas in which the movement currently finds itself, describing his subject as “the place of human rights in the history of moral opinions and modern schemes of progressive reform.”

Moyn takes a revisionist and decidedly minority stance compared with more conventional histories of human rights. Generally, historians mark the beginning of human rights with the revolutions—American and French—of the late 18th century, with traces leading back to the Bible and Greek philosophy and forward to the 1945 formation of the United Nations and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

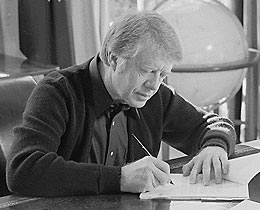

President Jimmy Carter |

But Moyn rejects these usual starting points, instead positing the 1970s, and especially the crucial year of 1977, as the true moment of the birth of the human rights movement. “In the 1970s,” Moyn writes, “the moral world of Westerners shifted, opening a space for the sort of utopianism that coalesced in an international human rights movement that never existed before.” The paradigmatic year—perhaps the movement’s zenith as well—began in January with Jimmy Carter’s inaugural address in which for the first time an American president made human rights a centerpiece of American foreign policy, and ended in December with the presentation of the Nobel Peace Prize to Amnesty International, the organization that pioneered and embodied a transnational understanding of human rights.

Moyn’s dating of the full-fledged human rights movement to the 1970s rather than 1776, 1789, or the 1940s is dependent on two things: the failure of other universalistic systems or utopias such socialism, anticolonialism, or democracy promotion wedded to laissez-faire capitalism, and the transcendence of the nation-state as the site for and enabler of human rights.

In Moyn’s view, as long as rights were linked to nation-state citizenship, as in the American and French revolutions, and to the nation-building of the anticolonial movement or the narrow foreign policy interests of the Cold War and the neo-conservative pro-democracy movement, then human rights could not be realized in a morally full and transcendent manner as a transnational ideal. The “central event” in the creation of human rights was the recasting of rights “that might contradict the sovereign nation-state from above and outside rather than serve as its foundation.”

During the revolutionary era of the 18th and 19th centuries, rights “were very much embedded in the politics of the state, crystallizing in a scheme worlds away from the political meaning … [they] … would have later. The ‘rights of man’ were about a whole people incorporating itself in a state, not a few foreign people criticizing another state for its wrongdoing. Thereafter, they were about the meaning of citizenship.”

Similarly, Moyn writes that the “true goal” of the prospective United Nations as it was being hammered out in the post-World War II era was less about enshrining the rights of individuals over against the state than it was about establishing a balance of power among the states. In the end, he says, the idea of human rights, despite being bandied about primarily as wartime anti-Nazi propaganda, entered the final plans of the UN “as a negligible line buried in the proposal for an Economic and Social Council without any serious meaning.”

Eleanor Roosevelt with Universal Declaration |

Nor did human rights emerge, he notes, as some historians have suggested, as a response to the Holocaust. “In real time, across the weeks of debate around the Universal Declaration in the UN General Assembly, the genocide of the Jews went unmentioned, in spite of the frequent invocation of other dimensions of Nazi barbarity to justify specific items for protection, or to describe the consequences of leaving human dignity without defense.” Moyn acknowledges that “human rights crystallized as a result of Holocaust memory, but only decades later, as [they] were called upon to serve brand new purposes.” He speaks of the “increasing Christianization of human rights after World War II,” but characterizes the 1950s human rights rhetoric of Popes Pius XI and XII as “a throwaway line, not a well-considered idea” and “an empty vessel that could be filled by a wide variety of different conceptions.”

The bulk of Moyn’s extended essay is devoted to three moments in contemporary history and how they not only created the framework for but also, in his view, impeded the development of human rights: the creation of the United Nations, the rise of anticolonialism, and the development of international law. In a chapter called “The Purity of the Struggle,” Moyn traces the emergence of the human rights movement in the 1970s, paying critical attention to Russian and Eastern European dissidents such as Andrei Sakharov and Vaclav Havel, as well as President Carter’s foreign policy efforts (though without mentioning Patricia Derian, who served during the Carter administration as the nation’s first assistant secretary of state for human rights and humanitarian affairs), and crediting “the supreme importance of political Catholicism in Eastern Europe” and Amnesty International as a central player.

Human rights exploded in the 1970s, Moyn writes, “in direct relation to the breathtaking marginalization of the UN as the central forum for and the singular imaginative custodian of the [human rights] norms. For this outflanking of the UN, American internationalism during World War II and its postwar remnants provided no precedent. It was Amnesty International [AI] above all, whose origins Moyn situates in “Christian responses to the Cold War,” that “made this move most decisively.” In the wake of the failure of the Tehran conference of 1968 marking the 20th anniversary of the Universal Declaration, the need for a new kind of mobilization on behalf of human rights became apparent, and AI provided the model. Indeed, Moyn writes, “almost alone, Amnesty International invented grassroots human rights advocacy, and through it drove public awareness of human rights generally.”

Yet it seems too much to argue that the movement had no real antecedents and somehow sprang full-blown from Jimmy Carter and his speech writers, or Vaclav Havel and Charter 77, or the founders of Amnesty International. It is interesting to note that in a bibliographical essay on additional research that appears at the end of the book, Moyn goes only so far as to acknowledge the work of many other scholars as a “quixotic search” for the deep roots of human rights. For those interested in “claims” about the deep Christian sources of human rights, he refers readers to philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff’s 2008 book “Justice: Rights and Wrongs” (Princeton University Press).

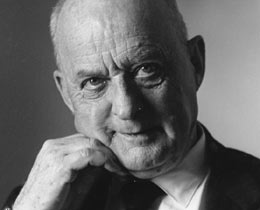

Reinhold Niebuhr |

Religion, nevertheless, runs through Moyn’s account like a red thread, sometimes notable in its impact, sometimes negligible, sometimes less than clear, and sometimes negative, as when Reinhold Niebuhr, the great apostle of internationalism and realism in foreign policy, criticized any proposed injection of human rights into the Dumbarton Oaks framework for the UN on the grounds they would be meaningless. “Nor would the Dumbarton Oaks agreements be substantially improved by the insertion of some international bill of rights which has no relevance, and would have no efficacy in a world alliance of states,” Niebuhr argued. “It is nonetheless true,” Moyn writes, “that against Niebuhr’s advice advocacy groups kept human rights on the agenda in the winter of 1944-45.” Moyn also notes the collaboration of the NAACP, under the direction of W.E.B. Du Bois, with Jewish and Christian organizations like the American Jewish Committee and the Federated Council of Churches “to return the idea of human rights to more prominence in the prospective [UN] charter.”

Moyn is telling a large and complex story concisely and often persuasively, even if he does not give enough credit to alternative versions. But there are many times when the reader wants more details and more context, especially about the role of religion, even though Moyn acknowledges that in the US “it was religious groups who were probably the most active in the campaign to raise the profile” of human rights. At least one reading of his argument suggests that US religious groups—especially the “old-stock Protestants” of the Federal Council of Churches and Jewish organizations like the American Jewish Committee, along with philosophers such as Jacques Maritain (“rights talk seems to have been dominated by Catholics,” Moyn observes at one point), Protestant Swiss theologian Emil Brunner, Anglican bishop of Chichester George Bell, religious peace groups, and Christian layman and Republican foreign policy thinker John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower’s secretary of state, for whom a Christian concept of human rights was “the last best defense against the communist threat”—all played an important role in the post-World War II debates around the formation of the United Nations in keeping the idea of human rights alive, even if its fully formed version did not come to fruition until the 1970s, and by that time, Moyn says, human rights “lost the religious associations” that had counted for so much in the 1940s.

Lebanese-Christian diplomat Charles Malik |

Moyn notes “the striking prominence of Christian social thought” among the three main framers of the Universal Declaration. In different ways, he writes, Christianity defined the worldviews of lawyer John Humphrey, who directed the UN’s Human Rights Division for two decades; Lebanese diplomat Charles Malik; and Eleanor Roosevelt. Even Amnesty International, which Moyn considers critical in the development of a full-blown, transcendent and untainted human rights movement, had its roots in Christian peace movements, including Quakers, Pax Christi and the World Council of Churches (although Moyn observes that neither Pax Christi nor the WCC “had made human rights a central idea.”)

“It was in the atmosphere of the crisis of utopias old and new [in the 1970s] that human rights broke through,” Moyn writes. The stalemate of the Cold War, the end of the anticolonial movement for self-determination—in short the failure of politics fired a longing for a movement and a meaning beyond nation-state politics. What distinguished human rights consciousness in the 1970s was that its appeal to morality “could seem pure even where politics had shown itself to be a soiled and impossible domain,” says Moyn. “Morality, global in its potential scale, could become the aspiration of humankind.”

But what might be called the pure human rights moment of moral vision passed from the scene almost as quickly as it had arrived, and human rights advocates were forced, Moyn argues, to confront the need for a political agenda and a programmatic vision. “If human rights were born in antipolitics, they could not remain wholly noncommittal toward programmatic endeavors, especially as time passed.”

In an epilogue on “The Burden of Morality,” Moyn looks at the new constraints and obstacles facing the movement, because despite transnational treaties aimed at protecting human rights, the nation-state did not wither away and human rights rhetoric—though not necessarily human rights realities—became another tool in the arsenal of national diplomacy.

One of the major issues facing human rights groups today is how to combine the political rights that fueled such groups as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch with the social rights—work, housing, food—that were also a part of the formulation of human rights in the 1948 Universal Declaration. Slowly, Moyn notes, there has been an amalgamation of the human rights movement and the humanitarian movement. Today, he says, “human rights and humanitarianism are fused enterprises, with the former incorporating the latter and the latter justified in terms of the former.”

Moyn is writing as a historian, not an advocate, so he does not address the still incomplete record of the human rights movement in responding to the so-called war on terror and the erosion of political rights with such legislation as the Patriot Act, the use of torture by the United States and other governments against alleged terrorists, or the possible violation of the Geneva Conventions or other international laws and norms in the name of national security. He does, however, observe that “human rights are not so much an inheritance to preserve as an invention to remake—or even leave behind—if their program is to be vital and relevant in what is already a very different world than the one into which it came so recently. No one knows yet for sure…what kind of better world human rights can bring about.”

To date, the human rights movement seems to have been singularly ineffective in offering or enacting the transnational utopian moral vision Moyn believes so distinguished it in the 1970s.

David E. Anderson, senior editor for Religion News Service, has written recently for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on artist Mark Rothko, drone warfare, and the ethics of sanctions.