James Wolfensohn on Religion and Development

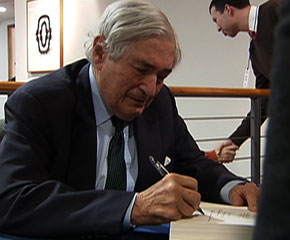

James Wolfensohn led the World Bank from 1995 to 2005. While he was at the helm, he pushed the Washington-based institution to develop an unprecedented relationship with religious groups. Wolfensohn recently returned to Washington to promote his new autobiography, “A Global Life” (Public Affairs Books, 2010). Kim Lawton sat down with him at the Aspen Institute.

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: During his decade as president of the World Bank, James Wolfensohn was a force to be reckoned with. And whether he was being praised for pushing new efforts to help the world’s poor or people were protesting against him for not doing enough, Wolfensohn sparked an unprecedented international conversation about poverty and development. I asked him if he believes the United States has a moral obligation to help poorer countries.

JAMES WOLFENSOHN: Personally, I believe so, and it is the stated intention of just about every president to make a contribution on the field of poverty and in the field of development. And I think they make the assumption that the nation agrees with that. That it is something that is part of the American ethic and that if we can help we should. What we haven’t done is to do it at the level of many other nations and I’m not sure we’ve done it always as effectively as we might. But in terms of intention and in terms of the right thing to do, I think we are absolutely where we should be.

LAWTON: Promoting international development is not only the right thing to do, he says, but the practical one as well.

WOLFENSOHN: I regard it as a moral responsibility. I think also though in terms of peace and security on our planet, it’s important to have economic development because countries that are moving forward economically by and large don’t attack other countries. If you can develop a more peaceful and prosperous world, it makes opportunities for export, it makes opportunities for business, but at the other end of the spectrum, it makes less likely terrorist acts and wars.

WOLFENSOHN: I regard it as a moral responsibility. I think also though in terms of peace and security on our planet, it’s important to have economic development because countries that are moving forward economically by and large don’t attack other countries. If you can develop a more peaceful and prosperous world, it makes opportunities for export, it makes opportunities for business, but at the other end of the spectrum, it makes less likely terrorist acts and wars.

LAWTON: But with a relentless recession and high unemployment rates, Wolfensohn acknowledges it can be difficult to convince Americans that they should still send aid to other countries.

WOLFENSOHN: And at a time like that it’s not surprising that we tend to look inwards to try and see how we can do something that would solve our own problems. But what you can’t do is just forget outside the country to deal with that.

LAWTON: During his tenure at the World Bank, Wolfensohn raised eyebrows by developing a new dialogue between his very secular institution and top leaders of the international religious community.

WOLFENSOHN: A very substantial part of aid to people in poverty goes through religious organizations. And secondly, the people that are in the field significantly, in addition to aid workers, are religious workers. And so it occurred to me that if we could get a dialogue between the people that were interested in development and religious leaders, we might have the basis for far greater cooperation and far greater understanding of the learning of each group.

LAWTON: Was that a hard sell within the World Bank itself, within that culture?

WOLFENSOHN: I think they all thought I was mad, to be quite honest. I won’t say all, but I don’t think I had a lot of support. But one of the great things about the World Bank is that if you’re president of it, you have quite a lot of discretion on what you do. And I would have to say that personally I found it amongst the most important initiatives that I took—very little talked about, by the way.

LAWTON: On three separate occasions, Wolfensohn and other bank officials met with religious leaders across the spectrum to discuss how they could work together to address global poverty.

WOLFENSOHN: And it was sort of fun for me as a nice Jewish boy from Australia bringing together all these great religious leaders.

WOLFENSOHN: And it was sort of fun for me as a nice Jewish boy from Australia bringing together all these great religious leaders.

LAWTON: Wolfensohn says he believes the meetings accomplished a lot.

WOLFENSOHN: Once we got them talking, as you know better than I they don’t always share secrets with one another about what they’re doing because in a sense there is a competitive element amongst religious leaders. But when you get to the question of humanity and the question of poverty, I found that the competitive element disappeared and we were able to talk about these fundamental humanitarian issues on a very even basis, and it was one of the great experiences of my life was chairing those meetings.

LAWTON: The meetings planted seeds for religious activism that continues, such as a massive interfaith march in support of the UN’s Millennium Development Goals. Wolfensohn believes such efforts must continue.

WOLFENSOHN: The most broadly based access to the developing world is through religious people. There are more of them out there. They’ve been there longer. They know the countries. They’re installed locally. They don’t all sit in a big office in the headquarters. They’re out in the field. And so it is a tragedy if they are not embraced, in my opinion, in the overall development process.

LAWTON: After he left the World Bank, Wolfensohn was appointed by President Bush to be a Middle East envoy. He says there the role of religion can be important but difficult.

WOLFENSOHN: It is not as though Islam, Judaism, or Christianity are monolithic. They’re not. And so I think you can, at the fringes, and at the margins and on particular issues, you can get help from the religious community. But I don’t think it is very easy to get them to come up with the solution for you.

LAWTON: Wolfensohn is still active in international development issues. One of his priority projects is an initiative helping train young Arabs to get jobs. He says he’s also concerned that young Americans be prepared for a globalized future.

WOLFENSOHN: We have to really revamp our education system, not just in maths and science, which I think we should, but in terms of humanities, and in terms of where our kids are going in the world, and we’re just not training them.

LAWTON: The world is getting smaller, he says, and America can’t afford to ignore that.

I’m Kim Lawton in Washington.