In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Ernest Gaines

BOB FAW, correspondent: Ernest Gaines is older now, 78, and hobbled by a bad back, but as he slowly makes his way to the church where as a boy he rang the bell at funerals he will not, indeed, cannot forget the debt he owes to his ancestors in this Louisiana bayou country.

ERNEST J. GAINES: Without them, buried back there under those pecan trees, I would not be the writer today, if I would be a writer at all.

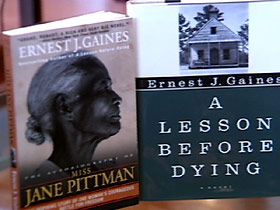

FAW: For more than 50 years, he has brought them to life in short stories and novels, some made into major films. Perhaps his most famous novel, “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,” charts the dawn of the civil rights movement from her days as a slave.

From “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman”: “I’ve been carrying a scar on my back ever since I was a slave.”

FAW: Miss Jane Pittman was inspired by Gaines’s Aunt Augusteen, whom he calls the greatest influence in his life.

FAW: She could not walk.

GAINES: She could not walk. She crawled over the floor all her life, but she did everything in the world for me.

GAINES: She could not walk. She crawled over the floor all her life, but she did everything in the world for me.

FAW: She could not walk, but you say she taught you how to stand.

GAINES: Right. By her action, by her overcoming all the obstacles.

FAW: Gaines remembers his aunt and other forebears as he sits in the church which he has restored on plantation land where he once picked cotton.

GAINES: When I’m sitting in the church alone, I can hear singing of the old people. I can hear their singing and I can hear their praying, and sometimes I hum one of their songs.

FAW: And Gaines feels so indebted to his elders that on his own property he has also lovingly restored and now maintains this cemetery where many of those elders are buried.

GAINES: I’d always go back to the cemetery and sit on one of those tombs back there, and I felt more at peace at that time than any other time in my life. I could feel their spirit there with me.

FAW: That connection helps explain why Gaines writes so passionately about the people and places in his past—because he worries that past is facing extinction.

From “A Gathering of Old Men”: “That tractor was getting closer and closer to the graveyard, and I got scared that that tractor would plow up them graves and get rid of all the proof that we ever was.”

GAINES: All writers write about the past, and I try to make it come alive so you can see what happened.

GAINES: All writers write about the past, and I try to make it come alive so you can see what happened.

FAW: John Lowe, professor of literature at Louisiana State University, is an expert on Ernest Gaines.

PROFESSOR JOHN LOWE: He’s writing for his people. You know, there’s an old African proverb that says no people should be hungry for their own image. That world was missing, and he’s put that world on the stage now.

FAW: There is in that world darkness, then hope. In “A Lesson Before Dying,” an innocent man, Jefferson, will be executed. But before that he learns to face death with dignity.

From “A Lesson Before Dying”: “Good-bye, Mr. Wiggins. Tell the children I’m strong. Tell them I am a man.”

LOWE: His works radiate that spirituality that Gaines has always seen as part of the human condition—that man has to believe in something bigger than himself, and it might be religion, it could be any number of things. Jefferson does walk to the electric chair as a man, because he has come to understand that his life has meaning for other people in the community, and it makes a big difference to them how he handles that situation, and so he does, indeed, endorse something bigger than himself.

FAW: Through Jefferson’s transformation his teacher, Grant Wiggins, also grows and emerges stronger.

From “A Gathering of Old Men”: “Ain’t going to be no lynching tonight.”

FAW: And in “A Gathering of Old Men” an entire community, long beaten down, finds self-respect.

MARCIA GAUDET: There is a sense of hope.

MARCIA GAUDET: There is a sense of hope.

FAW: Marcia Gaudet is the director of the Ernest J. Gaines Center at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

GAUDET: It may not be perfectly optimistic hope, but there’s certainly the possibility of hope, and that’s a much more realistic thing.

FAW: Raised a Baptist, Gaines attended Catholic school for three years. He doesn’t want readers to overstate religious symbolism in his work, but many scholars find it there—from Miss Jane Pittman’s religious conversion to the Christ-like figure of Jefferson in “A Lesson before Dying.”

LOWE: Gaines was raised in a religious tradition, and this is a pretty religious state even today, and it’s quite understandable that his work would be permeated everywhere, you know, with this kind of religious symbolism. In the South, our great mythology is the Bible. It’s not Greek or Roman myth like it is in Europe. It’s the Bible.

From: “A Gathering of Old Men”: Go home, Jameson. I don’t want to have to tell you anymore.”

FAW: Black clergymen in Gaines’s novels are sometimes portrayed as sanctimonious and ineffectual. When in “A Gathering of Old Men” a group of black men stand up to white oppression for the first time in their lives, the minister tries to stop them.

From: “A Gathering of Old Men”: “Reverend Jameson, nobody listening to you today. You old bootlegger, shut up.”

LOWE: Gaines understands the importance of the church, particularly during the civil rights movement. But at the same time he’s also aware because of the way the white community imposed it on the slave community to keep blacks in line. I think he has a very mixed attitude about the church.

LOWE: Gaines understands the importance of the church, particularly during the civil rights movement. But at the same time he’s also aware because of the way the white community imposed it on the slave community to keep blacks in line. I think he has a very mixed attitude about the church.

FAW: For the black church, Gaines is awed by its role as a sanctuary.

GAINES: What I miss today more than anything else—I don’t go to church as much anymore—but that old-time religion, that old singing, that old praying which I love so much. That is the great strength of my being, of my writing.

FAW: Do you regard yourself as a religious person?

GAINES: I think I’m a very religious person. I think I believe in God as much as any man does. I don’t only believe in God, I know there’s God.

FAW: Gaines wrote the first draft of all his novels by hand. While he isn’t writing much now, he still remembers 1948, when he first left the plantation land around False River, carrying with him an imaginary block of wood.

GAINES: The old people told me that okay, you can leave us, but you would carry this, this symbolic big piece of wood that I must struggle with for the rest of my life until I’ve completely finished that wood, which I doubt that I ever will. But there will always be something to chip away and to carve into something nice and beautiful.

FAW: Ernest Gaines—honoring the past, making it come alive because he must.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly this is Bob Faw in Oscar, Louisiana.