LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: The protesters are here each weekday morning—not a lot of them, but they are not alone. What began in Sierra Vista, a town about 80 miles southeast of Tucson, as a quiet merger between the Sierra Vista Regional Health Center and the Catholic Carondelet Health Network has turned into a religious and ethical standoff over patients’ rights.

THERESE ERICKSON (Cochise Citizens for Patients Rights): The moral issue for me is that they wish to take my moral choice away. I think I’m very capable of making my moral choices, and I’ve done pretty good for 67 years.

SEVERSON: What the merger means is that Sierra Vista, a rural, secular hospital, must now abide by the Catholic ethical and religious directives which prohibit certain procedures. So physicians can no longer do abortions, even when the mother’s life is in danger, and they can no longer perform sterilizations or provide contraception.

DOTTI WELLMAN (Cochise Citizens for Patients Rights): This county has one of the highest teen pregnancy rates in the country, not just the county. Immediately when this arrangement went in there would be no talk of birth control. If we had two hospitals, we would not be here, because there would be a choice.

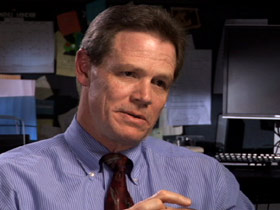

SEVERSON: One doctor has quit, and others who work at Sierra Vista, like Dr. Robert Holder, an ob-gyn, are very upset. .

SEVERSON: One doctor has quit, and others who work at Sierra Vista, like Dr. Robert Holder, an ob-gyn, are very upset. .

DR. ROBERT HOLDER (Sierra Vista Regional Health Center): I would say that the majority of the medical staff is not really happy with the fact that this is occurring and the way it came about. It was hard for us, thinking long term, how this was going to work out practically.

SEVERSON: Dr. Bruce Silva, another ob-gyn at Sierra Vista, says Catholic directives often go against health care decisions he and his patient think are best.

DR. BRUCE SILVA (Sierra Vista Regional Health Center): The person who makes that decision is not me and the woman. We can make that decision, but then it has to be okay’d by someone else who puts their belief systems and their ethics on me and on my patients, which I just don’t think is right.

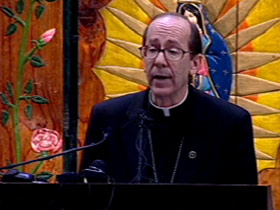

SEVERSON: Right or wrong, the Catholic Church takes its directives very seriously. Last year, Bishop Thomas Olmsted of the Catholic Diocese of Phoenix cracked down on this hospital, St. Joseph’s, after a doctor terminated the pregnancy of a mother who had developed pulmonary hypertension, which has a high mortality rate among pregnant women.

DR. HOLDER: It was not an either-or case. That baby was not going to survive because the mother was not going to survive, so the decision is that you let both die or you terminate the pregnancy so the mother can live, and to me that’s a no-brainer.

SEVERSON: But Bishop Olmsted disagreed with the doctors.

SEVERSON: But Bishop Olmsted disagreed with the doctors.

BISHOP THOMAS OLMSTED (speaking at Catholic Diocese of Phoenix December 21, 2010 Press Conference): In this case, the baby was healthy and there were no problems with the pregnancy. Rather, the mother had a disease that needed to be treated. But instead of treating the disease, St. Joseph’s medical staff and ethics committee decided that the healthy eleven-week-old baby should be directly killed.

SEVERSON: Bishop Olmsted stripped St., Joseph’s of its 116-year-long Catholic affiliation and excommunicated Sister Margaret McBride, the nun who had approved the abortion.

SEVERSON: Rev. Thomas Weinandy is the executive director for the Secretariat of Doctrine at the US Conference of Catholic Bishops. He and Richard Doerflinger, who handles bioethics issues for the conference, defended the church’s ethical and religious directives which, they say, are based on Gospel teachings about the dignity of life.

SEVERSON: So you support the Bishop Olmsted’s ruling with St. Joseph’s in Phoenix?

RICHARD DOERFLINGER (Associate Director, Secretariat of Pro-Life Activities, US Conference of Catholic Bishops): Bishop Olmsted has the authority to make the right decision. Personally, I support it.

REVEREND THOMAS WEINANDY (US Conference of Catholic Bishops): If you directly said the mother could not live unless we aborted the child then that would be contrary to Gospel values and the teaching of the church.

SEVERSON: So you would not perform an abortion on a child even if it meant saving the life of the mother?

SEVERSON: So you would not perform an abortion on a child even if it meant saving the life of the mother?

DOERFLINGER: You would try everything else to save her life except directly kill someone else. There are times when the mother needs treatment to save her life or prevent some other terrible injury that is going to lead as a side effect to risking the child’s life, maybe ending the child’s life, and that’s acceptable in Catholic teaching, because you’re intent is not to take the child’s life. It’s to treat the woman’s life.

SEVERSON: You have a child that is conceived because of incest or rape. Same?

REV. WEINANDY: Well, sure. You don’t just kill somebody because of their—how it happened. That doesn’t make their life any less worthy of living.

SEVERSON: Dr. Holder tells of a mother who had miscarried one of her twins and was about to lose the other.

DR. HOLDER: We were advised to send that person 80 miles away to another hospital because there was a heartbeat, and that was a very difficult situation for me to manage.

DR. SILVA: Some people will define abortion if a baby has a heart rate, and you terminate that pregnancy—it’s an abortion. But there are times, for instance, with a pregnancy in the fallopian tube, where babies will have heart rates but that baby can’t survive there. It’s impossible. So there are some places where they do not allow you to terminate that baby. This is the real problem is that it’s defined differently by different bishops, who are the ones that decide how your hospital is going to run.

SEVERSON: Officials at the Sierra Vista Regional Health Center declined to be interviewed, but the circumstances here are not unique. Catholic hospitals have become the largest nonprofit health care provider in the US, with over 600 hospitals. This year, one in six patients will be cared for in a Catholic hospital.

SEVERSON: Officials at the Sierra Vista Regional Health Center declined to be interviewed, but the circumstances here are not unique. Catholic hospitals have become the largest nonprofit health care provider in the US, with over 600 hospitals. This year, one in six patients will be cared for in a Catholic hospital.

DR. SILVA: I have worked at Catholic hospitals before, and I have no problems with that. I think Catholic hospitals do great care. But it was in a larger city where there was another hospital there, so women had a choice. Here we are very rural.

JESSICA GRAHAM: I’m Jessica Graham to see Dr. Silva, okay?

SEVERSON: Sierra Vista’s new directives posed a very real problem for Jessica Graham, who was going to have her second baby by c-section at Sierra Vista and then get a tubal ligation, or have her tubes tied. She and her husband didn’t want any more children.

GRAHAM: So I said, can you tie my tubes while I’m in surgery for a c-section? And when I got pregnant that was the option and that was the plan. Then it changed during my pregnancy when they did the merger here.

DR. SILVA: When I do a cesarean section, the woman is open already, and so if I do the tubal ligation it adds nothing to the risk that she has. But I can’t do them here.

SEVERSON: So Jessica was forced to have a second surgery in another city, which could have created problems.

DR. SILVA: People get infected, people can get bowel injuries. You can have a reaction to the anesthetic that can kill people. People die from tubal ligations every year—now very, very, very rarely, but why undergo that risk?

DR. SILVA: People get infected, people can get bowel injuries. You can have a reaction to the anesthetic that can kill people. People die from tubal ligations every year—now very, very, very rarely, but why undergo that risk?

REV. WEINANDY: The fact that they can’t get, receive sterilization or abortions at a Catholic health care facility is not a form of suffering at all. It’s a matter of fact that we are protecting them from evil things that could happen to them.

SEVERSON: Doctor Silva says his Sierra Vista patients can’t get the standard of care they deserve and that some simply can’t afford a second operation at another hospital. He says when he worked at a Catholic Hospital 20 years ago, tubal ligations were permitted.

DR. SILVA: But politically things change. You get someone who is a little more conservative in, and they now stop you from doing that.

DOERFLINGER: I don’t think it has anything to do with politics. It has to do with the language of the directives, which are a reflection of Catholic teaching and the bishops’ theological understanding of what that requires.

SEVERSON: Another concern for the protesters outside Sierra Vista is what happens with their end-of-life wishes if the Catholic Church doesn’t agree with them.

CHARLES GORDON (Cochise Citizens for Patients Rights): If I’m in a bad place I want to be able to direct them, “Hey pull those tubes.” They won’t kill me, I know that.

DR. SILVA: They talk about the fact that all of your end-of-life wishes will be observed unless they go against Catholic teaching. The problem is what does that last line mean?

DOERFLINGER: They are not going to stand back and watch if you are doing something they think is basically just trying to make yourself dead, but they are also going to respect your decisions about how burdensome a treatment to accept, how far to go in terms of prolonging your life when you know that you are on a course toward the dying process.

SEVERSON: Dr. Holder says in these hard economic times he understands the need for smaller hospitals like Sierra Vista to hook up with a larger health care service. But he thinks there are more suitable non-Catholic partners out there, and he’s hopeful that one will come along.

DR. HOLDER: I don’t think they quite expected the push-back from the community, and I think it’s at least opened their eyes to think that maybe we need to re-look at this and look at some alternatives.

SEVERSON: The merger process is not completed and won’t be for months. Doctors hope for a compromise, but they realize that the Catholic Church won’t be changing its directives.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson in Sierra Vista, Arizona.

Editor's Note: According to local media, on March 29, 2010 the president of Sierra Vista Regional Health Center announced that its agreement with the Catholic Carondelet Health Network is expected to be canceled in early April.