In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

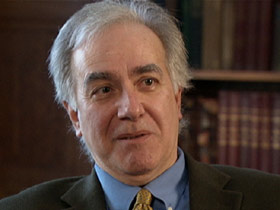

Carlos Eire

PROFESSOR CARLOS EIRE (speaking to class at Yale University): In 1517, something happens that has happened many times before…

BOB FAW, correspondent: Carlos Eire is at a pinnacle of the academic world. With an endowed chair at Yale, where he teaches religious studies, he’s also written six books, including the memoir “Waiting for Snow in Havana,” which won the National Book Award. But just as remarkable as his rise from Cuban refugee to professor of distinction is Carlos Eire’s spiritual odyssey.

EIRE: It is an incomprehensible and in many ways an indescribable experience. What had been scary to me, what had been frightful, suddenly turned into the most beautiful thing.

FAW: In pre-Castro Cuba, Eire’s was a life of privilege—the festive holidays and lavish birthday parties at grand estates befitting the son of a wealth and influential judge and a gorgeous mother. But their Spanish Catholicism terrified young Carlos.

FAW: In pre-Castro Cuba, Eire’s was a life of privilege—the festive holidays and lavish birthday parties at grand estates befitting the son of a wealth and influential judge and a gorgeous mother. But their Spanish Catholicism terrified young Carlos.

EIRE: There was no place in the world scarier for me as a child than a church. Actually my worst nightmare was being locked in a church all night long, because the images were so frightening.

FAW: What tormented him most, Eire recalls, was his father’s collection of icons of Christ.

EIRE: The crown of thorns on his head bleeding. It was in his study, right near the Jesus plate with the eyes that followed you.

FAW: Eire’s comfortable life came crashing down when Fidel Castro seized power. Only 11, Eire knew his life had changed when the new regime prevented him from seeing a Walt Disney film, “20000 Leagues Under the Sea,” that he had already seen seven times.

EIRE: That was the turning point for me. I really felt like someone was trying to steal my soul, not just invade but claim it as their own, some authority outside of me, and that’s when I just began to see everything in a different light.

EIRE: That was the turning point for me. I really felt like someone was trying to steal my soul, not just invade but claim it as their own, some authority outside of me, and that’s when I just began to see everything in a different light.

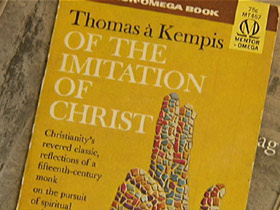

FAW: Fearful, their world collapsing, Eire’s parents sent him and his brother, Tony, to the United States in 1962, two of 14,000 Cuban children airlifted from Cuba in an operation dubbed “Pedro Pan.” Like many of the other children, Carlos and Tony lived with foster families. Never again would they see their father, and their mother would join them only years later. When Carlos left Cuba, his parents gave him a book which they said would bring him comfort.

EIRE: It was “The Imitation of Christ” by Thomas à Kempis—for centuries had been a very popular text in Spanish-speaking cultures. It’s all about self-denial. It’s about not being part of the world. It’s very monastic in its outlook.

FAW: You wrote in the Miami book, “It scared me half to death. It is the most depressing book ever written by any human being in all of human history.”

EIRE: From a child’s perspective, yes, definitely.

FAW: But in Miami, living with foster parents who were Jewish but who made him go to a Catholic church every Sunday, Eire was unshackled for the first time from the Catholicism of Cuba and its troubling images of pain and suffering.

EIRE: After I had come to the US and seen churches that were free of such images, I realized that Spanish Catholicism and Latin American Catholicism was very different from American Catholicism in that respect and sort of put a less scary pall over religion.

EIRE: After I had come to the US and seen churches that were free of such images, I realized that Spanish Catholicism and Latin American Catholicism was very different from American Catholicism in that respect and sort of put a less scary pall over religion.

FAW: Later, when Eire and his brother moved in with his uncle in Illinois, there were no more gory images of Jesus.

EIRE: My uncle had this very Protestant image of Jesus above his armchair—totally unscary, a friendlier, more accessible Jesus.

FAW: Though liberated from the demons of his youth, Eire says he was still plagued, even crippled by what he calls “the void.”

EIRE: It attacked me, because it seemed to come from outside of me. it was a feeling of utter abandonment and emptiness and having no connection to anything or anyone, and having no one or anything beyond one’s self. Everything was turning dark.

FAW: But as Carlos Eire so movingly writes in his second memoir, “Learning to Die in Miami,” that overwhelming despair was shattered on Holy Thursday 1965 in a profound religious experience.

EIRE: It was at that period when I started reading “The Imitation of Christ,” not just little passages, but actually getting into the meaning, and it brought me to this experience, a profoundly religious experience. I think it’s fair to call it a conversion experience.

EIRE: It was at that period when I started reading “The Imitation of Christ,” not just little passages, but actually getting into the meaning, and it brought me to this experience, a profoundly religious experience. I think it’s fair to call it a conversion experience.

FAW: “Everything changes,” you wrote. “Everything changes from top to bottom. A void rips loudly and light pours through.”

EIRE: Up until that point I always thought that spirit was insubstantial. It’s with that experience that I realized that spirit is more substantial than matter, because it is connected to eternity. Time stops. All there is is now, and this now is forever.

FAW: After experiencing what he calls “that presence,” Carlos Eire says religion became his salvation and he was able, he says, “to let go.”

EIRE: Thinking that there’s something beyond this life helps one immensely in letting go. Without some other dimension, letting go, to me, is too painful—impossible.

FAW: You wrote, “He who knows best how to let go will enjoy the greater peace, because he is conqueror of himself.”

EIRE: Letting go of your attachment to things and even your attachment to your own will and your own attempt to make sense of the world your own way and kind of open yourself up to something higher.

FAW: Not all those haunting images from his past have been excised. He anguishes, he says, over what is happening in Cuba today.

FAW: Not all those haunting images from his past have been excised. He anguishes, he says, over what is happening in Cuba today.

EIRE: I could not, in a sense, stop feeling the pain. The so-called free education and free medical care come at the cost of slavery. Cubans right now are no different than slaves in a plantation in the American South before the Civil War. Europeans and Canadians who go to Cuba to have a good time—I can’t understand it. It would be like vacationing in the Third Reich and having a good time and ignoring Auschwitz.

FAW: And while Cuba, he says, “is a wound that will not close,” the scars from his earlier religious trauma have healed.

EIRE: Yes, there is pain and suffering, but it can be transcended, and it can be redemptive. I was able to let go of everything I had lost, including my parents, and I was able to focus on what the purpose of life should be. Not as regaining everything I had lost, but rather giving one’s self to others.

FAW: Carlos Eire—a long way from Cuba, but waiting no more.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly this is Bob Faw in New Haven, Connecticut.