In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Organ Donation

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: It’s early morning at Washington Hospital Center and time for a quick prayer before Flavia Walton heads into surgery. For eight years, Flavia’s husband, Bill, has had severe kidney disease, and Flavia is donating a kidney. But her kidney isn’t going to Bill. They weren’t compatible enough—at least when it came to kidneys. So Bill had to be put on the transplant list.

BILL WALTON: You are placed on the list, and then the wait begins, and it goes on and on and on, and your only hope is you can check the list on the Internet and see if the numbers are getting any smaller. But they never do.

LAWTON: Then Bill and Flavia heard about a program known as a paired kidney exchange, where Flavia could donate her kidney to somebody else, and in exchange Bill would get a kidney from another donor who was a perfect match.

BILL WALTON: Bottom line here is you’ve got to give one to get one.

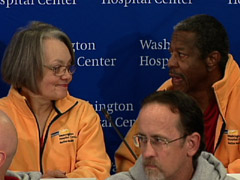

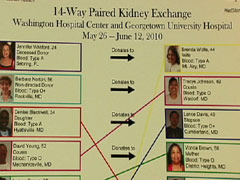

LAWTON: The Waltons were part of the world’s largest kidney swap to date, sponsored by Washington Hospital Center and Georgetown University Hospital. It involved a complex chain of 28 surgeries at four different hospitals. Most of the donors gave a kidney in order to benefit a friend or family member. But a couple of donors did it out of a sense of altruism, with no particular recipient in mind. In the end 14 patients who had been particularly hard to match received kidney transplants. The donors and recipients were introduced to each other at an emotional news conference.

LAWTON: The Waltons were part of the world’s largest kidney swap to date, sponsored by Washington Hospital Center and Georgetown University Hospital. It involved a complex chain of 28 surgeries at four different hospitals. Most of the donors gave a kidney in order to benefit a friend or family member. But a couple of donors did it out of a sense of altruism, with no particular recipient in mind. In the end 14 patients who had been particularly hard to match received kidney transplants. The donors and recipients were introduced to each other at an emotional news conference.

RALPH WOLFE (kidney donor speaking at press conference): I love this guy. I don’t even know him, but I love him.

GARY JOHNSON (kidney recipient speaking at press conference): You can’t imagine how fortunate I feel that somebody from somewhere in the universe came and gave me a kidney.

FLAVIA WALTON (speaking at press conference): To see someone that you love most in the world deteriorate is a sense of helplessness and powerlessness that you just cannot comprehend unless you’ve been there. But to be able to do something is so empowering, but it is such a blessing.

LAWTON: More than 100,000 Americans are currently on the waiting list for an organ transplant, the vast majority of them waiting for a kidney. Over the last decade, an estimated 60,000 people died while still waiting for a transplant. Given those numbers, many experts say there is a moral obligation to encourage more people to become organ donors.

PROFESSOR ROBERT VEATCH (Kennedy Institute of Ethics, Georgetown University): Just a little nudge would do enormous amounts of good in terms of saving lives and making sick people’s lives better.

PROFESSOR ROBERT VEATCH (Kennedy Institute of Ethics, Georgetown University): Just a little nudge would do enormous amounts of good in terms of saving lives and making sick people’s lives better.

LAWTON: The incentive for Flavia Walton to become an organ donor was clearly to benefit her husband of 42 years.

FLAVIA WALTON: If God could give his son for me, or for us, I could certainly give a kidney to keep someone else alive. And I certainly want to keep him around as long as possible. I don’t know if he wants to keep me around that much longer.

BILL WALTON: No, I got no complaints.

FLAVIA: Okay, okay. But no, it was not a hard decision at all.

LAWTON: Living donors are screened psychologically to ensure they are not being unduly pressured into the surgery. It is major surgery, but because of medical advances the risks to the donors are quite low. Because of these factors, Professor Veatch at Georgetown University’s Kennedy Institute of Ethics says there are few ethical problems with kidney swaps such as the one the Waltons were part of.

VEATCH: If we can get a living donor we get a better kidney, a more viable kidney, and it shows up in the survival-rate statistics.

LAWTON: His main ethical concern with the swaps is making sure that kidney patients without a loved one willing to donate are not pushed lower on the waiting list, particularly those with hard-to-match blood types.

LAWTON: His main ethical concern with the swaps is making sure that kidney patients without a loved one willing to donate are not pushed lower on the waiting list, particularly those with hard-to-match blood types.

VEATCH: We at least want to be fair with the people on the wait list who don’t have a family member available. Being fair might mean waiting a trivial extra amount of time, but we certainly don’t want to make those people wait years extra just because of the swap arrangements.

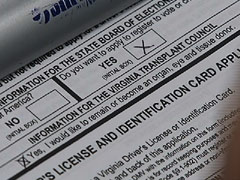

LAWTON: While the swap program has been successful, some other strategies to encourage organ donation have run into roadblocks because of the National Organ Transplant Act, which forbids any monetary compensation for organ donation. Twenty-five years ago, Veatch testified in support of that law, but he’s now urging that it be revisited. He’s calling for experimentation with some token financial incentives. For example, he would support a modest discount on driver’s license renewals for people who sign up to be organ donors. Or, he says, there could be a question on income tax returns asking people to be donors, and even offering a tax deduction for those who say yes.

VEATCH: It sort of taints the altruism of organ donation. On the other hand, real human lives are at stake here, and I would be willing to compromise the altruism at the margins if we can really save some lives.

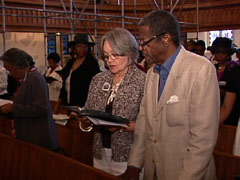

LAWTON: Veatch also says the religious community should do more to promote organ donation.

LAWTON: Veatch also says the religious community should do more to promote organ donation.

VEATCH: It’s considered an altruistic, charitable act, and all the major religions look favorably upon that behavior.

LAWTON: Veatch tries to counter one theological concern he hears among some conservative Christians, especially in the black church, who believe individuals will be bodily resurrected in the end times, and therefore they worry about the implications of organ donation.

VEATCH: The doctrine is when you are resurrected you will be resurrected to look like you, but with all the bad stuff fixed. So if you had cancer, the cancer won’t be there, and if organs had been procured, or consumed by fire, you will get a new version of the body.

LAWTON: Flavia Walton, who is a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, says she tries to address that theological issue in her community as well.

FLAVIA WALTON: I think that there’s some notion or some belief among many that feel that when we meet our maker, we have to meet our maker all in one piece. For me, it means I just want to meet the maker. I don’t think the maker cares whether I’m all in one piece or not. I don’t think that’s the issue.

LAWTON: The Waltons say organ donation is of particular concern to African Americans because more than 60 percent of patients who need transplants are non-white. At the same time, African Americans have a disproportionately low rate of organ donation. The Waltons hope their story can help change that.

LAWTON: The Waltons say organ donation is of particular concern to African Americans because more than 60 percent of patients who need transplants are non-white. At the same time, African Americans have a disproportionately low rate of organ donation. The Waltons hope their story can help change that.

BILL WALTON: Exposure is key, and the more we can expose to that population that it works and we’re examples of that, the more emphasis we can get out there that spread the word and let’s proceed.

LAWTON: After two years on dialysis, Bill says he can’t believe how great he feels now. He says the gift of someone else’s kidney has meant everything to him.

BILL WALTON: Life, basically. You can’t get any more basic than that—life with a little ginger thrown in, because it’s a life that is much more comfortable than what I had.

LAWTON: Flavia says donating a kidney turned out to be a spiritual experience for her, definitely worth the short time she spent recovering from surgery.

FLAVIA WALTON: Just feeling good that I’ve been able to do something and that hopefully I’ll be able to make a difference not only in the life of the recipient of my kidney, but hopefully it’ll spread, and hopefully I’ll be able to make a difference in helping other people make a decision to make a difference in the lives of others.

LAWTON: And as politicians and ethicists wrestle over how to encourage more organ donations, the Waltons hope stories like theirs will be the best incentive of all.

I’m Kim Lawton in Washington.