In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Tax Justice

TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: There are some things the government must do, and the first reason for taxes is to pay for them. Beyond that there is wide debate over how taxes can be efficient and fair and what kind of society they should promote.

PROFESSOR GREG MANKIW (Professor of Economics, Harvard University): People on the left think that the tax code is not nearly redistributive enough, think that the rich are really getting away with murder. People on the right think that it’s not the job of government to be redistributing income and that the tax code we have is too progressive.

O’BRIEN: Greg Mankiw was the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers in the second Bush administration.

MANKIW: It’s a difference of values, of what you think government should be. In coming to any sort of tax reform those different values are going to collide, and there’s no easy way to sort of reconcile these very different philosophical positions about what the scope of government should be.

MANKIW: It’s a difference of values, of what you think government should be. In coming to any sort of tax reform those different values are going to collide, and there’s no easy way to sort of reconcile these very different philosophical positions about what the scope of government should be.

Professor Michael Sandel teaching at Harvard: How should income and wealth and opportunities and the good things in life be distributed?

O’BRIEN: The collision of the competing views of the role of government is the grist for a very popular course at Harvard taught by Michael Sandel, a professor and political philosopher.

PROFESSOR MICHAEL SANDEL (Professor of Government, Harvard University): The main purpose of a tax system is to raise revenue for the common good, for the public good. That’s its purpose. But it has to do so in a way that is fair, that involves shared sacrifice, because really it’s a matter of sharing the burdens of a free society and of a good society. That’s, morally speaking, what taxes are about. So unless a tax system meets the test of fairness, none of its other advantages really matter.

O’BRIEN: For Peter Wehner, a former deputy assistant to President George W. Bush, the issue is freedom.

PETER WEHNER (Senior Fellow, Ethics and Public Policy Center): This country was founded on liberty. It wasn’t founded on income equality. And there is a certain view, which I subscribe to, which says that people ought to be able to keep much or most of what they earn and to have the government in the business of taking it and deciding how it, government, will spend it rather than you as an individual I think is flawed, and I think it’s contrary to much of the American tradition, and I happen not to think that it’s consistent with ethical or moral or religious traditions as well.

PETER WEHNER (Senior Fellow, Ethics and Public Policy Center): This country was founded on liberty. It wasn’t founded on income equality. And there is a certain view, which I subscribe to, which says that people ought to be able to keep much or most of what they earn and to have the government in the business of taking it and deciding how it, government, will spend it rather than you as an individual I think is flawed, and I think it’s contrary to much of the American tradition, and I happen not to think that it’s consistent with ethical or moral or religious traditions as well.

O’BRIEN: But according to Michael Sandel, fairness—“sharing the burdens of a free and good society”—may compel a significant redistribution of wealth.

SANDEL: Some people do work harder than others, but what’s reflected in the vast income inequalities that we’ve seen in recent years is not hard work primarily. School teachers work hard, bus drivers work hard, kindergarten teachers, daycare workers—they work hard. Do they work less hard than hedge fund managers and Wall Street bankers who reap hundreds and thousands of times what they do in the market economy? Most of the wage differences, most of the income differences have very little to do with differences in effort. Most of them have to do with supply and demand and with the qualities that our society happens to value, and a lot of this is no doing of the people who are lucky enough to have those talents and those abilities to wind up on top. And if that’s true, then it seems to me there is an obligation for those who are affluent, those who succeed under this system, to share their bounty with those who through no fault of their own are less well off.

O’BRIEN: In Alabama, which has its share of “less well-off,” families falling below the poverty level still pay income taxes and a hefty nine percent tax on groceries, while many wealthy property owners pay next to nothing in property taxes. Schools suffer, and some families find it even harder, because of taxes, to put food on the table. The Alabama legislature is composed almost entirely of Christians, but to one critic the state’s tax policy stands Christian values on their head.

O’BRIEN: In Alabama, which has its share of “less well-off,” families falling below the poverty level still pay income taxes and a hefty nine percent tax on groceries, while many wealthy property owners pay next to nothing in property taxes. Schools suffer, and some families find it even harder, because of taxes, to put food on the table. The Alabama legislature is composed almost entirely of Christians, but to one critic the state’s tax policy stands Christian values on their head.

PROFESSOR SUSAN PACE HAMILL (Professor of Law, University of Alabama): The moral principles of Judeo-Christian ethics demand that our taxes raise a level of revenue embracing the reasonable opportunity of all and that the burden be allocated in a moderately progressive way.

O’BRIEN: Susan Hamill is seminary trained, a United Methodist, a tax attorney, and a law professor at the University of Alabama, and she’s made a name for herself crusading for tax reform in Alabama based on Judeo-Christian ethics—the Bible.

HAMILL: The Bible, first and foremost, absolutely forbids oppression—this is where I got started with this in Alabama—forbids oppression. What is oppression? Oppression is taking a person who’s already down, who is struggling, who is vulnerable and making their situation worse, actively doing so.

HAMILL: The Bible, first and foremost, absolutely forbids oppression—this is where I got started with this in Alabama—forbids oppression. What is oppression? Oppression is taking a person who’s already down, who is struggling, who is vulnerable and making their situation worse, actively doing so.

O’BRIEN: The idea that those who write our tax laws should be in any way guided by religious beliefs has been greeted with a degree of skepticism by some leading economists, like Greg Mankiw.

MANKIW: I don’t think one can go straight from any sort of religious view to what an optimal tax system looks like, but in terms of thinking about fairness and what’s the role for government—sure, I think all of our values come into play.

O’BRIEN: There’s no debate that tax laws should be fair, but how in a pluralistic society such as ours do we even define the word “fair”? And assuming we can define it, how far should the government go using tax dollars to promote fairness?

WEHNER: The aim of tax policy is to generate economic growth. A rising tide lifts all boats. I don’t think that, as a general proposition, using tax policy to create fairness or equality works. To take money from the rich, money that they have earned because they have worked hard, is not by itself just, and again, if you take money from the rich beyond a certain point you’re going to create disincentives for wealth creators, and that’s going to have a huge effect on the poor as well.

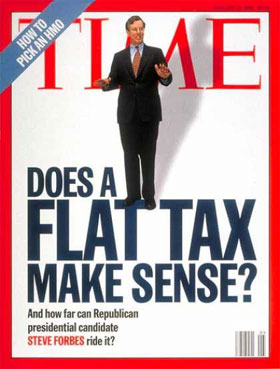

O’BRIEN: One remedy championed by Steve Forbes in his run for the presidency in 1996 is a flat tax—17 per cent across the board, scrapping the current complicated and loophole-laden IRS code. The flat tax may have antecedents in the religious tradition of tithing, where each person gives the same percentage regardless of income.

O’BRIEN: One remedy championed by Steve Forbes in his run for the presidency in 1996 is a flat tax—17 per cent across the board, scrapping the current complicated and loophole-laden IRS code. The flat tax may have antecedents in the religious tradition of tithing, where each person gives the same percentage regardless of income.

MANKIW: Well, I think a flat tax would for sure be more efficient, and I think the strongest argument in favor of a flat tax has to do with efficiency.

O’BRIEN: Many economists, like Harvard’s Greg Mankiw, say the government should rely less on taxing income and more on a value-added tax on consumer goods, a form of flat tax found in much of Europe.

MANKIW: It’s a consumption tax rather than an income tax, so it does not tax savings. So if I earn some money and I put it in the bank and I don’t spend it, it doesn’t get taxed until I take it out and spend it later on whatever I buy. And I think there’s a lot of economists have argued over the years that consumption is a better basis for taxation than income, because consumption is actually what we’re enjoying. And also saving is a part of economic growth, so if we exempt saving until it’s later consumed, it’s going to tend to promote economic growth. So I think there’s a strong case to be made for using consumption as the basis for taxation.

O’BRIEN: If, however, sacrifices are to be shared equally, some adjustment would have to be made for those who have little money at all and are hard pressed to cover even the most basic necessities. Our tax code may be the best measure of what kind of a people we are and what kind of a country we have created. The late American philosopher John Rawls defined a just society as one you would want to live in, even if you did not know in advance what your place in it would be—whether you would be rich or poor, male or female, or what your race or I.Q. would be. In his course at Harvard, Professor Sandel also questions whether a country committed to equal opportunity should allow the wealthy to pass on their vast fortunes to their children and grandchildren.

SANDEL: If we believe that everyone should have an equal chance to work hard and aspire and succeed, then it’s very difficult to justify that children of wealthy parents should have a huge advantage even before they start. The estate tax, quite apart from raising revenue, is a way a society says we want to give everyone equal opportunity as far as we can, and we don’t want to give a huge advantage to people, to let them start way before everyone else simply because they had the good luck, or the good judgment, to be born to affluent parents.

SANDEL: If we believe that everyone should have an equal chance to work hard and aspire and succeed, then it’s very difficult to justify that children of wealthy parents should have a huge advantage even before they start. The estate tax, quite apart from raising revenue, is a way a society says we want to give everyone equal opportunity as far as we can, and we don’t want to give a huge advantage to people, to let them start way before everyone else simply because they had the good luck, or the good judgment, to be born to affluent parents.

WEHNER: If your parents, upon dying, want to give their children the money rather than going to the government, that’s a perfectly reasonable thing to do. Is it fair to the children who by birth might get that money that it’s taken from them and it’s given to the government? I don’t think that there is an ethical or moral imperative to do that.

O’BRIEN: Even if political philosophers and economists could agree on the fairest and most efficient method of taxation, that surely doesn’t mean it will ever happen, because of the power of special interests, such as homeowners.

MANKIW: So why should the tax code subsidize home ownership, which is eventually at the expense of renters? On the other hand, trying to get rid of that is very hard, because homeowners think they’ve become entitled to it, so there’s no question that that’s going to be a hard one to get rid of, but it’s also the right thing to do. It’s easy for me to talk about tax reform. I have tenure. The typical congressman has to get reelected every two years, and so that makes their set of constraints much more troublesome and difficult to navigate than mine.

O’BRIEN: What the tax debate makes clear is just how divided the country is over how to define the role of government and the values it should promote.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Tim O’Brien in Washington, DC.