In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Sacred Remains

BOB FAW, correspondent: On that terrible day ten years ago, when New York City firefighters began responding to the attacks, firefighter Scott Kopytko found that his spot taken by a new recruit.

RUSSELL MERCER: And he was in his position…

JOYCE MERCER: All right. So Scott bumped him off the truck. He told him to get off the truck, you’re in my spot.

FAW: As Scott climbed the stairs of the South Tower to rescue people, it collapsed. Kopytko, 32, was killed. His remains have never been found. In his Forest Hills, New York, hometown, Kopytko is now honored at a small plot lovingly tended by his stepfather. It is the only memorial the family has, and they say it is not enough.

JOYCE MERCER: We’ve never been able to fully go through the normal process of death where you bury your loved one, you grieve, you remember all the good times. This we’ve been stunted in the middle. We know our son is dead, but we’ve never been able to lay him to rest.

RUSSELL MERCER: It’s like being deprived of something, like a meal or a loved one that you had. You don’t have that final solution. I mean, it’s insane. You don’t have no idea what we have to go through.

RUSSELL MERCER: It’s like being deprived of something, like a meal or a loved one that you had. You don’t have that final solution. I mean, it’s insane. You don’t have no idea what we have to go through.

DIANE HORNING: I think we live in a country where we assume we will be given proper burials. That’s not—but they weren’t. The 9/11 dead were scooped out of the site very quickly with bulldozers and backhoes and dumped into trucks and barges.

FAW: On 9/11, Diane Horning lost her 26-year-old son, Matthew, who was working on the 95th floor of the North Tower. She and some other families have fought hard to get the remains moved to a common burial site.

HORNING: We just want what every person in this country gets, which is a decent, respectful burial, which is what we gave Osama Bin Laden. I’m not angry that he had a burial with rites and rituals. I think that shows a common decency, and we want the same.

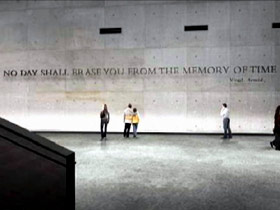

FAW: Despite intense efforts to find all the remains, the fact is of the 2753 people killed at the World Trade Center, the remains of more than 40 percent have not been identified. When the 9/11 memorial opens September 11, there will be no common burial site for the remains. Thousands of unidentified bone and body fragments will be placed near the museum behind a wall with an inscription from Virgil reading, “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.” There, scientists will continue trying to identify the remains. James Young is an expert on memorials.

PROFESSOR JAMES E. YOUNG (University of Massachusetts at Amherst): Once the families know that the remains are right nearby, for them the memorial experience then maybe is just a little bit too close to the forensic work going on in the medical examiner’s office. They look at that big wall, and that’s all they can think of, not just what’s behind it but that my loved one’s remains have not been identified yet. I have nothing to show.

PROFESSOR JAMES E. YOUNG (University of Massachusetts at Amherst): Once the families know that the remains are right nearby, for them the memorial experience then maybe is just a little bit too close to the forensic work going on in the medical examiner’s office. They look at that big wall, and that’s all they can think of, not just what’s behind it but that my loved one’s remains have not been identified yet. I have nothing to show.

FAW: Disaster ministries expert Peter Gudaitis counseled scores of relatives on proper arrangements.

PETER B. GUDAITIS (Executive Director, National Disaster Interfaiths Network): It’s been a very difficult path to follow, because there are religious accommodations that families expect and deserve and by law actually have a right to. At the same time, there are all sorts of complicated impracticalities to what remains that is identified, who are the custodians of those remains, and what are remains?

FAW: In a public letter, family members involved in the memorial planning process defend what is being done here, insist it is what most families want, and argue that since the remains will not be part of the museum’s space proper, nor will they be seen by the public, that those remains are being treated “with the utmost care, respect, and reverence.” But the plan to shelter remains underground near the museum where officials are considering charging an admission fee has troubled many. Diane Horning says she won’t go to the memorial.

HORNING: I don’t think there’s much dignity in that memorial at all. I will never go to it, and I would recommend that no one go to it. I think that it is a commercial enterprise. The most important thing is the building, not the people. I find that unethical, to take my son’s remains, the remains of the people with whom he died, and have it be a draw in a museum, in a pay-to-view museum.

HORNING: I don’t think there’s much dignity in that memorial at all. I will never go to it, and I would recommend that no one go to it. I think that it is a commercial enterprise. The most important thing is the building, not the people. I find that unethical, to take my son’s remains, the remains of the people with whom he died, and have it be a draw in a museum, in a pay-to-view museum.

FAW: The Mercers say they won’t visit the site of the remains.

RUSSELL MERCER: They’re just pushing us aside. Move out of the way, we want to get this done now. These men were heroes. After 9/11, the first responders, the New York City had them and the world had them walking on water. Now they’re going to put them seven stories below ground level. It’s a disgrace to these men, a total disgrace.

FAW: At the site of mass murder, whether at the memorial for victims of the Oklahoma City bombing, Ground Zero, or the Pentagon, victims are honored, memorialized—sites where great evil has been committed, but also consecrated, made into sacred ground, given the blood shed.

YOUNG: I for one don’t believe that there is an intrinsic sacredness in any site. We make them sacred in our visits. These sites become part of a national civic religion, in a way.

FAW: The 9/11 victims will be honored at the new 9/11 memorial with their names placed alongside two pools built in the footprint of the twin towers. Hundreds of memorials to the victims of 9/11 have been built in the last ten years. In Hazlet, New Jersey, in the shadow of the goalposts where he played high school football, victim Steve Paterson is remembered. In Guatemala, four houses have been constructed in Matthew Horning’s name, and along the boardwalk at the New Jersey shore he so loved, there is a bronze memorial plaque. What is needed now, says his mother, is a final resting place, like the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

FAW: The 9/11 victims will be honored at the new 9/11 memorial with their names placed alongside two pools built in the footprint of the twin towers. Hundreds of memorials to the victims of 9/11 have been built in the last ten years. In Hazlet, New Jersey, in the shadow of the goalposts where he played high school football, victim Steve Paterson is remembered. In Guatemala, four houses have been constructed in Matthew Horning’s name, and along the boardwalk at the New Jersey shore he so loved, there is a bronze memorial plaque. What is needed now, says his mother, is a final resting place, like the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

HORNING: I think that this Tomb of the Unknown should have been accessible to everyone, because it is something that happened to everyone. We have all changed, and I would like this ability to pay respect, to contemplate.

RUSSELL MERCER: That was the way I was brought up. Have some place where you can honor the remains of your loved ones. There’s no honor there, no place I can go in private, on the holidays.

JOYCE MERCER: Well, we know what happened to our Scott, but I don’t feel he’s at rest, and we can’t be at rest.

FAW: Ten years later then, despite painstaking labor here and all the effort to respect the wishes of surviving relatives, what seems clear is that no memorial can bring complete comfort, much less serve as a final resting place.

GUDAITIS: There is that sense of yearning, that loss, that reopened wound, this scabbed, you know, wound. It’s this kind of wound in the city that’s never been healed. It is a constant reminder that there’s still a chance that they could find some part of their loved one but that it’s not complete. Nothing’s complete. The journey isn’t complete.

FAW: And until it is, no matter how successful this memorial, some will continue waiting quietly with their memories and pain or tenderly maintain their own tributes for loved ones who disappeared on 9/11, and who they fear are disappearing again.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly this is Bob Faw in New York.