The Perfection of English and the Making of the KJB

by David E. Anderson

At the end of the “almost entirely secular” funeral for singer Michael Jackson, Pastor Lucious Smith, in a concluding prayer, reminded mourners that “even now the King of Pop must bow his knee to the King of Kings. And we pray that you would remind us, Lord, that our lives are but dust.”

Renaissance studies professor Gordon Campbell writes that this incident is emblematic of the melding of contemporary popular culture with the words of a 400-year-old translation of the Bible. “The formality of the language acknowledges its origin in the KJV,’’ he observes in his book Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611-2011 (Oxford University Press). While the modern idiom would be “bend his knee,” the use of “bow” recalls instead the repeated use of this idiom in the King James Version. Similarly, “our lives are but dust” echoes “he remembereth that we are dust” (Psalm 103:14), but it does so, Campbell says, in an archaic construction in which a negative is suppressed. The word “but” becomes adverbial and means “merely,” a construction common to the KJV.

Campbell’s book is one of a host of recently published and forthcoming books on the King James Bible’s 400th birthday, an occasion that is providing scholars and other commentators with an opportunity to praise and, if not bury, at least restore some measure of balance in assessing its importance, its influence, and its possible future significance.

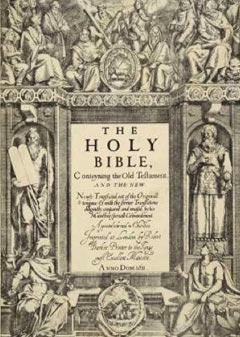

It is fair to say the King James Bible is one of the most popular and, in many quarters, beloved books in the English language. At one time in the not too distant past it could be found in virtually every Protestant home in the United States. Along with Shakespeare, it is thought to have had an uncommonly large influence on the English language.

Campbell’s Bible is an excellent place to begin to sort through the history and influence of the King James Bible. Century by century, in England and America, Campbell guides the reader in accessible but thorough scholarship through the pre-King James beginnings of the Bible in English to the contemporary world where the KJV is available in a Kindle edition and MP3 formats.

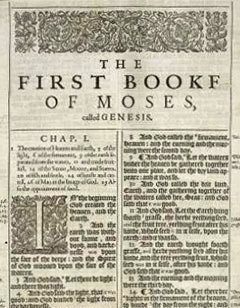

Some of the history will be familiar, but other parts will be new and even startling or unsettling, especially to those who believe the 1611 text is the unalterable word of God. For example, Campbell notes the text of the KJV was not fixed in 1611, and there was no master first edition. “The absence of an agreed master text gave license to a long tradition of corrections, and there was not always a clear line drawn between corrections of printers’ errors and corrections of translators’ errors.”

Indeed, the stabilization of the text did not come until 1769, when English divine Benjamin Blayney’s Oxford folio was published. “The KJV that one can buy now,” Campbell observes, “is essentially this late-eighteenth century text, not the text of 1611.”

In succinct but informative chapters, Campbell moves through the pre-history of the King James Bible, beginning with the seminal figure of John Wycliffe. Although many think of Wycliffe as the first translator of the Bible into English, Campbell informs us while Wycliffe encouraged a number of translations by his followers, “there is no evidence that he undertook any translating himself.” Still, by the end of the fourteenth century “the English Bible was firmly associated with his name.”

In succinct but informative chapters, Campbell moves through the pre-history of the King James Bible, beginning with the seminal figure of John Wycliffe. Although many think of Wycliffe as the first translator of the Bible into English, Campbell informs us while Wycliffe encouraged a number of translations by his followers, “there is no evidence that he undertook any translating himself.” Still, by the end of the fourteenth century “the English Bible was firmly associated with his name.”

Campbell also helpfully reminds us of the chief aim of Protestant Bible translators such as Wycliffe and, on the continent, reformers such as Luther and Erasmus: to put the Scriptures into the hands of the everyday laity. Henry Knighton, Wycliffe’s chronicler and contemporary, complained that the English church reformer “translated from the Latin into the language not of the angels but of Angles [the English], so that he made the Bible common and open to the laity, and to women who were able to read, which used to be reserved for literate and intelligent clergy.”

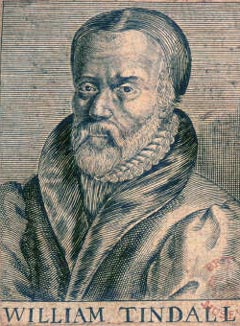

Wycliffe was the first but not the last Protestant associated with translation who would be martyred for his efforts. Since David Daniell’s definitive 1994 biography of Bible translator William Tyndale (1494?-1536), that English reformer with Lutheran sympathies has been getting increased attention for his major contribution to the King James Bible. Although he has often been overlooked by those who lavish extravagant praise on the KJB, especially for its literary merits, Campbell says Tyndale should be rightly known as “father of the English Bible,” and while he only completed translations of the New Testament, the Pentateuch, and the Book of Jonah, Tyndale was a looming presence in the 1611 version. Many of the phrases and cadences associated with the KJB, from “Let there be light and there was light” to “Ask and it shall be given you; seek and ye shall find; knock and it shall be opened unto you,” came first from Tyndale. According to David Katz in his 2004 book God’s Last Words (Yale University Press), the portions of the King James Bible that Tyndale translated remain about 90 percent verbatim Tyndale. Yale critic Harold Bloom argues Tyndale should be ranked “one of the greatest writers in English, standing only after Shakespeare, Chaucer and Milton,” and as New Testament scholar Gergely Juhász writes in his essay in the collection The King James Bible after 400 Years: Literary, Linguistic, and Cultural Influences (Cambridge University Press), edited by Hannibal Hamlin and Norman W. Jones, “To put it somewhat bluntly: by modern standards of authorship, the KJB would be regarded as a form of plagiarism.”

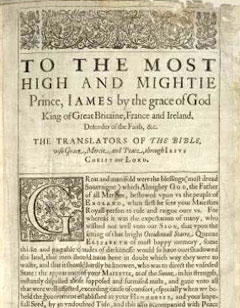

After a synopsis of each of the major translations prior to the King James Bible, Campbell provides a useful overview of the commissioning of the King James Version, noting the king’s desire for an alternative to the popular but anti-monarchical Geneva Bible, as well as glimpses at individual translators and the organization of the translation companies. Readers seeking a fuller examination of the politics and personalities involved in the creation of the King James Bible might also turn to Adam Nicholson’s God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible (HarperCollins). Published in 2003, Nicholson’s highly readable, but sometimes excessively florid, account of the complex world of Jacobean England goes deeper into the intrigues and controversies swirling through England in the post-Elizabethan age, especially the Hampton Court conference of Puritans and bishops from the established English Church that aimed to reconcile the two increasingly cantankerous factions.

After a synopsis of each of the major translations prior to the King James Bible, Campbell provides a useful overview of the commissioning of the King James Version, noting the king’s desire for an alternative to the popular but anti-monarchical Geneva Bible, as well as glimpses at individual translators and the organization of the translation companies. Readers seeking a fuller examination of the politics and personalities involved in the creation of the King James Bible might also turn to Adam Nicholson’s God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible (HarperCollins). Published in 2003, Nicholson’s highly readable, but sometimes excessively florid, account of the complex world of Jacobean England goes deeper into the intrigues and controversies swirling through England in the post-Elizabethan age, especially the Hampton Court conference of Puritans and bishops from the established English Church that aimed to reconcile the two increasingly cantankerous factions.

Nicholson provides fascinating sketches of the translators and others who played a role in bringing the King James Bible to life. He is especially good on the complex character of Lancelot Andrewes, Dean of Westminster Abbey, who, says Nicholson, is in many ways the flawed hero of the King James Bible’s story: “as broad as the great Bible itself, scholarly, political, passionate, agonized, in love with the English language …. Worldly, saintly, serene, sensuous, courageous, craven, if not corrupt then at least compromised, deeply engaged in pastoral care, generous, loving, in public bewitched by ceremony, in private troubled by persistent guilt and self-abasement—but in the grim realities of plague-stricken London in the summer of 1603, he appears in the worst possible light.” During the long months of the plague, Nicholson says, Andrewes never once visited his parish of St. Giles, Cripplegate, where more than a third of its 4,000 people died.

While the stricter Puritans were disappointed with the 1604 Hampton Court conference because no great change to the established church was enacted, “at court an air of optimism prevailed,” Nicholson writes. “The English Church would be unified, its Elizabethan squabbles forgotten. England and Scotland would become one country. Peace would be established in Europe. There would even be discussions with the pope about the reunification of the Roman and Protestant churches. … James’s Arcadian vision of untroubled togetherness would descend on the soul of England like a balm.”

While the stricter Puritans were disappointed with the 1604 Hampton Court conference because no great change to the established church was enacted, “at court an air of optimism prevailed,” Nicholson writes. “The English Church would be unified, its Elizabethan squabbles forgotten. England and Scotland would become one country. Peace would be established in Europe. There would even be discussions with the pope about the reunification of the Roman and Protestant churches. … James’s Arcadian vision of untroubled togetherness would descend on the soul of England like a balm.”

“Much of that looks like a joke now,” Nicholson adds. “Almost the only remnant of that dream, a piece of flotsam after the tide has passed, is the King James Bible.”

Like Nicholson and others, Campbell pays special attention to the brief given to the translators. They were “not to make a new translation … but to make a good one better.” Indeed, the first rule the translators were to follow was begin with “the ordinary Bible read in the church, commonly called the Bishops’ Bible, to be followed and as little altered as the truth of the original will permit.”

As he follows the changing text through the centuries, Campbell corrects some common ideas about the KJB. He says the notion that it was published on May 2 is a myth, for there was no such thing as a publication date in the seventeenth century. He also provides interesting details on other aspects of Bible publication, such as the first introduction of chronologies to accompany the text (in 1679), which dated Adam’s death at 130 anno mundi (“year of the earth”). A more famous chronology by Church of Ireland Archbishop James Ussher, which dated the creation precisely to the evening preceding Sunday, 23 October 4004, was added in 1701.

Campbell says the unhappy Puritans were broadly content with the translation, although a little uneasy about the inclusion of the Apocrypha. Others over the years were less accepting. Despite the near unanimity in praise for the KJB that exists today—a “cascade of delight,” English professor Stephen Prickett calls it in his essay on “the King James steamroller” in The King James Bible after 400 Years—it was not especially well-received when it was published or for some decades thereafter. After 1611, while the KJB was the Bible required to be read in English churches, “There was widespread grumbling, from all corners, about both its scholarship and its style,” editors Hamlin and Jones write. Critics found it a rushed job, the equivalent of scholarly fast-food, in which “the cook hasted you out a reasonable sudden meal,” in the words of Protestant clergyman and scholar Ambrose Ussher, brother of the famous archbishop. Others called it harsh, uncouth, and obsolete. Indeed, Prickett argues that acclaim for the KJB really dates only from the beginning of the nineteenth century, and then for literary rather than religious reasons.

Campbell says the unhappy Puritans were broadly content with the translation, although a little uneasy about the inclusion of the Apocrypha. Others over the years were less accepting. Despite the near unanimity in praise for the KJB that exists today—a “cascade of delight,” English professor Stephen Prickett calls it in his essay on “the King James steamroller” in The King James Bible after 400 Years—it was not especially well-received when it was published or for some decades thereafter. After 1611, while the KJB was the Bible required to be read in English churches, “There was widespread grumbling, from all corners, about both its scholarship and its style,” editors Hamlin and Jones write. Critics found it a rushed job, the equivalent of scholarly fast-food, in which “the cook hasted you out a reasonable sudden meal,” in the words of Protestant clergyman and scholar Ambrose Ussher, brother of the famous archbishop. Others called it harsh, uncouth, and obsolete. Indeed, Prickett argues that acclaim for the KJB really dates only from the beginning of the nineteenth century, and then for literary rather than religious reasons.

As religious belief waned during the Victorian era, recognition grew for the King James Version’s importance to the English language and to British and American literary life. Prickett is explicit: praise for the KJB, when it comes, is presented as exclusively aesthetic.

Poet and historian Thomas B. Macaulay wrote in 1828 that the English Bible was “a book which, if everything else in our language should perish, would alone suffice to show the whole extent of its beauty and power.” Literary historian and critic George Saintsbury, writing toward the end of the nineteenth century, called it, along with Shakespeare, “the perfection of English, the complete expression of the literary capacities of the language.” Even a religious skeptic like H.L. Mencken, writing in 1930, said it was “probably the most beautiful piece of writing in all the literature of the world.”

Harold Bloom, one of the most prominent and prolific, as well as controversial, contemporary literary critics, echoes Saintsbury in his book The Shadow of a Great Rock: A Literary Appreciation of the King James Bible (Yale University Press), arguing the KJB stands at “the sublime summit of literature in English” alongside only Shakespeare. “Originally the culmination of one strand of Renaissance English culture,” Bloom writes, “the KJB became a basic source of American literature: Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson are its children, and so are William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, Cormac McCarthy. The KJB and Shakespeare fuse into a style of language that enabled the emergence of Leaves of Grass, Moby-Dick, As I Lay Dying, Blood Meridian. Whitman’s verse and Hemingway’s prose alike stem from the KJB.”

While Bloom does not explore those large claims in his contribution to the cornucopia of books celebrating the KJB anniversary, eight of the essayists in the Hamlin-Jones collection do, examining the influence and impact of the King James version on figures from John Milton, John Bunyan, and the Romantic poets to John Ruskin, Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, and William Faulkner, as well as on African-American literature more generally and on lesser known—in the United States, at any rate—writers Jean Rhys and Elizabeth Smart.

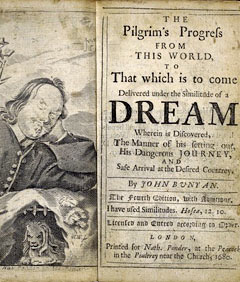

Hannibal Hamlin, for example, in his essay on John Bunyan (1628-1688), best known for The Pilgrim’s Progress, observes that while writers had been making allusions to or paraphrasing and adapting the Bible long before the King James Bible, Bunyan “had the remarkable ability to transport himself into and live inside his favorite book … the Bible.”

Hannibal Hamlin, for example, in his essay on John Bunyan (1628-1688), best known for The Pilgrim’s Progress, observes that while writers had been making allusions to or paraphrasing and adapting the Bible long before the King James Bible, Bunyan “had the remarkable ability to transport himself into and live inside his favorite book … the Bible.”

“Pilgrim’s Progress is all Bible, all the time,” Hamlin writes. But the question is, which Bible? Bunyan, like many Protestants in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, had access to more than one translation. Hamlin says there are some instances where the KJB and the Geneva Bible, the translation most popular with Puritans and other dissenters, diverge, and it seems Bunyan had Geneva in mind. But the Bible he clearly knew best was the KJB, and “the vast majority of identifiable biblical quotations and allusions in Grace Abounding and Pilgrim’s Progress are either decisively KJB or in language shared by KJB and Geneva.”

Hamlin goes on to observe: “One of the peculiarities of the history of the KJB is that the English Bible associated most strongly with a monarch and with the established church became the favored Bible of radicals and dissenters such as Bunyan. … The first major English writers who seem predominantly influenced by the language of the KJB are Milton and Bunyan.”

Similarly, it is worth noting—according to one of the essays in Manifold Greatness: The Making of the King James Bible, edited by Helen Moore and Julian Reid and published by the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford to mark its collaboration with the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, on a major exhibition on the development of the King James Bible—that KJB texts were so prominent in the works of great Nonconformist hymn-writer Isaac Watts and early Methodist Charles Wesley that if the KJB were lost, as one Wesleyan minister said, you could “extract much of it” from their hymns.

Perhaps one of the writers contemporary readers would find most unlikely to be influenced by the Bible is Virginia Woolf (1882-1941). Yet literary critic and New Yorker staff writer James Wood, in his essay on her novel To the Lighthouse (1927) in the Hamlin-Jones collection, finds it “stealthily biblical, and its visionary power all the stronger for the submersion and ghostliness of its biblical allusions.” One of the novel’s central questions, he argues, turns on what it means to continue to need or make use of religious language whose content is no longer believed in.

Perhaps one of the writers contemporary readers would find most unlikely to be influenced by the Bible is Virginia Woolf (1882-1941). Yet literary critic and New Yorker staff writer James Wood, in his essay on her novel To the Lighthouse (1927) in the Hamlin-Jones collection, finds it “stealthily biblical, and its visionary power all the stronger for the submersion and ghostliness of its biblical allusions.” One of the novel’s central questions, he argues, turns on what it means to continue to need or make use of religious language whose content is no longer believed in.

Wood looks in depth at the difficult “Time Passes” section of the novel to argue that what the passage seems to suggest “is that though an antique biblical language is needed to evoke the almost cosmic confusion of the First World War, that same biblical language will not suffice to disclose revelation, because the formal belief that sustained and enriched that language has disappeared; in this sense, when God died, the language of revelation died with him.”

“It is this post-Christian dimension that makes To the Lighthouse both the great elegy for the innocence destroyed by the First World War, and the great farewell, comparable to ‘Dover Beach,’ to the last, frail sureties of Victorian Christianity,” Wood writes.

Another fine essay in the Hamlin-Jones collection by Katherine Clay Bassard argues the African-American writer’s approach to the KJB “is based on a dual perception of the Bible as a book of signs and wonders” which represents in dialectical form the fascination with the language of the KJB “as the vehicle for social power and an acknowledgment of the spiritual authority bestowed on the Bible as a sacred text within African-American religious culture.”

Harold Bloom’s Shadow of a Great Rock takes a different and, of course, contentious approach to his consideration of the KJB. Instead of looking just at the influence the KJB has exerted on writers, he surveys many of the 66 books of the Bible itself, as well as the Apocrypha.

Like most literary critics who write about the importance of the KJB, Bloom devotes most of his space to the Hebrew Bible, where he applies the theory he developed in his The Book of J to write about aesthetic achievements of the writer he posits as responsible for the Bible’s first five books. He often takes issue with contemporary conventional biblical critical theory, not only in the case of the Pentateuch, but also in such cases as the authorship of Isaiah. “I am unimpressed,” Bloom writes in his comments on Isaiah, “by fashions in biblical scholarship, which currently dissolve the Yahwist (J) into a mosaic of fragments. Isaiah now is even more atomized.”

Like most literary critics who write about the importance of the KJB, Bloom devotes most of his space to the Hebrew Bible, where he applies the theory he developed in his The Book of J to write about aesthetic achievements of the writer he posits as responsible for the Bible’s first five books. He often takes issue with contemporary conventional biblical critical theory, not only in the case of the Pentateuch, but also in such cases as the authorship of Isaiah. “I am unimpressed,” Bloom writes in his comments on Isaiah, “by fashions in biblical scholarship, which currently dissolve the Yahwist (J) into a mosaic of fragments. Isaiah now is even more atomized.”

Bloom is even more provocative in his handling of the New Testament, or as he somewhat snarkily calls it “the Belated Testament.“ While he finds the Hebrew Bible’s compilation and canonization to be guided by an “implicit aestheticism,” there is no such overall literary merit or aesthetic motivation to the New Testament. “Usurpation is the stance of the Greek New Testament toward the Hebrew Bible,” and he finds that with the exception of Paul and James, the New Testament is “a viciously anti-Jewish work. Paul is anti-Judaic but not a hater of Jews.” The New Testament, Bloom says, “has hatred at its core despite its doctrine of love.”

His judgment of the Gospel of Mark is typical. “Like the J writer’s Yahweh, Mark’s Jesus is both a person and a personality. You cannot apprehend either J’s Yahweh or the Marcan Jesus by employing theology: it would not work. Both J and whoever wrote Mark are uncanny writers, but J is sublime and Mark is weird. I intend no deprecation of Mark by that distinction. J is a great writer, comparable to Homer and Tolstoy, while Mark reminds me of Edgar Allan Poe, a bad stylist who yet fascinates.”

For Paul, Bloom deploys his most famous critical insight, saying the apostle suffers “an anxiety of influence in regard to the Hebrew Bible. Seeking power and freedom, Paul tears to shreds the authority of Tanakh. … Usurpation is the central resource alike of the strong poet and the spiritual innovator. Not even Isaiah and Jeremiah were enough for Paul to overgo; Moses himself was to be surpassed.”

Along the way, however, Bloom engages in some useful comparative readings of Tyndale and the KJB, and he sets the two versions of 1 Corinthians 13 alongside each other to interesting effect. “Paul uses the Greek agape, caritas in Jerome’s Vulgate and so KJB’s ‘charity,’” he notes. “For me, Tyndale’s ‘love’ works better, and I also prefer his ‘I imagined as a child’ to the KJB ‘thought.’ Best of all is Tyndale’s ‘even in a dark speaking’ rather than the KJB ‘darkly.’ And yet again I must commend Tyndale over the apostle himself, strictly as a literary judgment.”

The King James Bible did not only exert a literary influence. History professor Naomi Tadmor, in her The Social Universe of the English Bible (Cambridge University Press), the most academic and philologically penetrating of the books under consideration, looks at a very different reciprocal relationship—the one between the translators and the social world in which they lived, the world they sought to reflect in their translations. A key reason for its popularity, she writes, is that the translation was “Anglicized” or “Englished.”

The King James Bible did not only exert a literary influence. History professor Naomi Tadmor, in her The Social Universe of the English Bible (Cambridge University Press), the most academic and philologically penetrating of the books under consideration, looks at a very different reciprocal relationship—the one between the translators and the social world in which they lived, the world they sought to reflect in their translations. A key reason for its popularity, she writes, is that the translation was “Anglicized” or “Englished.”

“The biblical text was not simply translated into English but also transposed, slightly molded or otherwise rendered in terms that made sense at the time,” she argues.

There are key shifts in meanings from Hebrew words to English words that were “textually telling and historically significant. … As the Bible was rendered into the vernacular … subtle and overt ‘Englishing’ also took place, which in turn plays a role in the widespread propagation of the English Bible.”

Such changes, she contends went beyond word and semantic substitutions to include the construction of a social universe. In four heavily footnoted chapters, Tadmor explores four sets of social relations and how the biblical translation and social circumstances interacted. In the first, she looks at how the Hebrew semantic construction “love thy friend” or “thy fellow man” evolved to become the English “love thy neighbor,” a very different injunction. The second chapter examines notions of gender and the ways in which English conceptions of marriage crept into the vernacular biblical versions over time, while the third chapter focuses on labor relations and how the Hebrew word that would literally be translated as “slave” was transformed into the English “servant.” The fourth chapter surveys notions of office and rule and the ways in which biblical terms were “Englished” and manifested in such renderings as “prince,” “captain,” “duke,” “sheriff,” and even “chamberlain,” which, she notes, is the ”sanitized term employed in some contexts for designating the Hebrew saris, meaning eunuch.”

Tadmor argues, for example, that by “rendering the word re’a as neighbor in the biblical translations, the moral relationship of the biblical injunction was conceived of in the English text as taking place in a social world shaped by local communities.” Similarly, she writes that the understanding of service relationships in early modern England found its way into the translations of the English Bible. She finds that the original Hebrew wording of the Ten Commandments, for example, makes no reference at all to servants in any conventional English sense of the word. Rather, the text mentions male and female slaves. “In the Fourth Commandment, for example, masters are instructed to allow their male and female slaves (as well as domestic animals) to rest on the Sabbath day. The Tenth Commandment concludes by prohibiting individuals from coveting not only their fellow man’s house, but also his chattels, including male and female slaves.”

Linguist David Crystal, in his delightful book Begat: The King James Bible and the English Language (Oxford University Press), sets out to test the assertion made in his 2004 book The Stories of English that “the King James Bible—either directly, from its own translators, or indirectly, as a gloss through which we can see its predecessors—has contributed far more to English in the way of idiomatic or quasi-proverbial expressions than any other literary source” and to quantify just how many expressions such as “salt of the earth”’ or “whited sepulcher” currently used in English have their roots in the King James Bible. But as he says in Begat, it is not quite as simple as that.

Linguist David Crystal, in his delightful book Begat: The King James Bible and the English Language (Oxford University Press), sets out to test the assertion made in his 2004 book The Stories of English that “the King James Bible—either directly, from its own translators, or indirectly, as a gloss through which we can see its predecessors—has contributed far more to English in the way of idiomatic or quasi-proverbial expressions than any other literary source” and to quantify just how many expressions such as “salt of the earth”’ or “whited sepulcher” currently used in English have their roots in the King James Bible. But as he says in Begat, it is not quite as simple as that.

The answer was both more difficult and complicated than he thought, and in 42 short, breezy, and often humorous chapters, Crystal looks at biblical expressions that have entered the common language. “The most interesting cases of the Bible shaping our language are when we find expressions in daily use, where people take a piece of biblical language and use it in a totally nonbiblical context, knowing that the allusion will be recognized.” Even better, he says, are cases where the biblical expression is linguistically manipulated to make people sit up and take notice. “The writers aren’t expecting us to know which bit of the Bible the allusion refers to, only that they’ve done something clever with the English language.”

Crystal cites as one example the phrase “let there be light,’’ noting that if one types the expression into a computer search engine there will be over a million hits but only a small minority directly related to the Genesis story. It has been put to use in all sorts of nonbiblical settings, including as a title for art exhibits and pop music. It even turned up as the name of an episode on the TV series “Sex and the City.”

“The best evidence that an expression has been fully assimilated into a language is when it generates creative, playful alternatives,” Crystal concludes. He notes blog reports on airline delays with titles such as “Let There Be Flight,” while boxing and wrestling Web sites go for “Let There Be Fight.” But “let there be light” is not unique to the KJB. It was in the earlier Tyndale and the Bishops Bible before it went into the KJB.

Another chapter looks at the phrase “fly in the ointment,” which Crystal notes has achieved a vogue in popular culture: it’s the title of two novels and a book on popular science, and in music it turns up as the name of a pop group as well as the title of a 1990s album by the US rock group AFI, as well as the name of at least two songs. But, he says, while all dictionaries cite the King James Bible as its source, the phrase doesn’t actually appear there with those words. The verse in Ecclesiastes (10:1) actually reads: “Dead flies cause the ointment of the apothecary to send forth a stinking savour; so doth a little folly him that is in reputation for wisdom and honor.”

Crystal finds Isaiah provides a number of expressions that have been turned into idioms, including the verse “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks.” He notes a headline in a Colombian newspaper about the decline of paramilitary activity and the rise of a local literature which read “beating swords into pens,’’ and the opening of a tea house on the site of a former battleground in Thailand leads to “beating swords into teacups.” A 2000 book on adapting military technology for civilian products was titled “Beating Swords into Market Shares.”

Crystal finds Isaiah provides a number of expressions that have been turned into idioms, including the verse “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks.” He notes a headline in a Colombian newspaper about the decline of paramilitary activity and the rise of a local literature which read “beating swords into pens,’’ and the opening of a tea house on the site of a former battleground in Thailand leads to “beating swords into teacups.” A 2000 book on adapting military technology for civilian products was titled “Beating Swords into Market Shares.”

The conflation of Isaiah 22:13, “Let us eat and drink; for tomorrow we shall die,’’ with Luke 12:19, about the rich man who tells his soul, “Take thine ease, eat, drink, and be merry,” winds up in all kinds of modern variations, such as “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we diet” or “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we devalue the pound” or “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow you may be in Utah,”’ a reference to the state’s strict alcohol laws.

Another Isaiah phrase, “Behold the nations are as a drop of a bucket” (Isaiah 40:15) has resulted in the modern idiom “drop of/in a bucket,” but, again, the phrase is not unique to the KJB and appears also in Wycliffe, Geneva, and the Roman Catholic Douai-Rheims.

So what does Crystal conclude at the end of his biblical combing and computer searching? He says the influence of biblical idioms is substantial, and they are found in all contexts in which language is used, “from ABC television to zoology, taking in on the way such varied domains as basketball, comic strips, dentistry, engineering, pornography and social networking. The people implicated cover all walks of life: Shakespeare and Sinatra, Byron and Beckham, Osama and Obama. The sources range from News of the World to Newsweek, from Henry IV to The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” Even the recent banking crisis has made a contribution: “Am I my Lehman Brothers’ keeper?”

Still, says Crystal, this remarkable and stylistic diversity stems from a surprising small number of instances of English idioms from the KJB—only 257. “I say ‘only 257’ because this puts in perspective the sometimes wild claims made about the role of the Bible in the history of the English language,” he writes, yet no other source, including Shakespeare, has contributed as many.

What about in the King James Version? Crystal says in only 18 cases is a modern idiom to be found in its exact form. In 37 cases, such as “fly in the ointment,” there is no exact King James antecedent. In some 196 cases another translation, especially the Geneva Bible, has the same form as the King James Bible. Is it right, then, to insist that no book has had greater influence on the English language than the KLB? “If this claim is interpreted with reference to the number of innovative idiomatic expressions in a single canonical work of literature, I think we have to say yes,” Crystal concludes.

But do the current anniversary observances celebrate the enduring and continuing importance of the King James Bible, or are they an elegy for an influence that has passed and that will render the KJB of antiquarian rather than theological or literary interest?

But do the current anniversary observances celebrate the enduring and continuing importance of the King James Bible, or are they an elegy for an influence that has passed and that will render the KJB of antiquarian rather than theological or literary interest?

“In 1986,’’ Indiana University English professor Paul C. Gutjahr notes in his essay “From Monarchy to Democracy” in the Hamlin-Jones collection, “the New International Version accomplished what dozens of other American translations had been unable to do: dethrone the King James Bible as the bestselling Bible version among American Protestants, a position it had held for nearly three hundred and fifty years.”

Gutjahr‘s piece explores the long tradition of Bible translation in America, pointing out that in the nineteenth century alone, American biblical scholars created some 30 new translations. While many of these received lukewarm receptions, new translations continued to appear with increasing frequency in the early decades of the twentieth century, including, in 1901, the American Standard Version, “a version which many American Protestants would revere throughout the century as the gold standard of translation accuracy.”

Gutjahr touches briefly on the controversy surrounding the publication of the Revised Standard Version in 1952, which brought into sharp relief the deepening divisions within American Protestantism between mainline and conservative evangelical denominations. In the wake of the RSV’s slow acceptance, new translations continued to appear, with nine in the 1950s alone. In the 1960s and early 1970s, however, two new versions of the Bible utilized a new understanding of translation—the American Bible Society’s Good News for Modern Man (1966) and The Living Bible (1971). Both used the controversial translation principle known as “functional equivalence,’’ which stressed translating the Bible “thought-for-thought,” rather than the “formal equivalence” method which translated “word-for-word.” Functional equivalence translations aimed to make the Bible more accessible and simpler to understand by flattening and limiting the interpretative possibilities of complex passages.

“While the quest to present Bible readers with a readily understandable vernacular translation reached all the way back to the KJB, the NIV became a shining example of the contemporary cost of such a mission as the NIV offered its readers ever narrower and more focused lines of interpretation,” Gutjahr writes. “As the voice of the KJB receded in American culture, not only did a multiplicity of scriptural voices become more prominent, but also these voices were increasingly inflected with distinct interpretative stances.”

The use of functional equivalence and the rise of what Gutjahr calls revolutionary changes in publishing have made the last 40 years an era dominated by the proliferation of highly interpretative niche Bibles—The Couples Bible, Policeman’s Bible, Extreme Teen Study Bible, and the Celebrate Recovery Bible, for example.

“Perhaps no biblical edition better captures the current spirit of the age when it comes to American Bible reading than The HCSB Light Speed Bible,” Gutjahr observes, a response to the fact that 40 percent of Bible owners say the book is too hard to read and 59 percent feel they don’t have the time to read their Bible. The Light Speed Bible fuses the Holman Christian Standard Bible with a reading system developed by author and lecturer William Proctor, which he promises will allow readers to read the entire Old and New Testaments in 12 to 24 hours with 70 percent comprehension. “Accessibility, efficiency, and ease of use have clearly become key values in the production and consumption of American Bibles,” says Gutjahr.

The consequences of the shift, both for the future of the King James Bible and for Americans’ biblical literacy, remain uncertain, but Gutjahr is pessimistic: “Not only is the popularity of the KJB dying in America, but with it is American biblical culture’s ability to benefit from the many-layered riches found in the Bible.”

David E. Anderson is senior editor for Religion News Service. He has written for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on American prose and the King James Bible and on John Updike, Marilynne Robinson, and many other writers.