In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

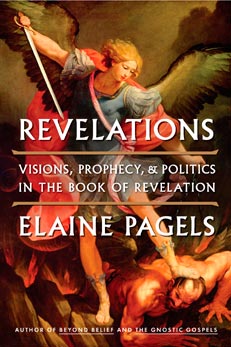

Elaine Pagels on the Book of Revelation

PROFESSOR ELAINE PAGELS (reading from the Book of Revelation): “And another sign appeared in heaven; a great red dragon with ten horns and seven diadems on his head. His tail swept down a third of the stars in heaven and cast them to earth. And the dragon stood before….”

BOB FAW, correspondent: For almost two thousand years, that fantastic, sometimes nightmarish language of the Book of Revelation has confused and inspired, It was the inspiration for paintings by William Blake, for the poetry of John Milton. Lyrics like “he hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword”: that too came from Revelation. Despite its profound impact, noted biblical scholar Elaine Pagels says Revelation remains “the strangest book in the Bible” and “the least understood.”

PAGELS: It’s the most controversial book in the Bible. It’s always been that. Some people thought it didn’t belong there at all. And other people wanted to throw it out. Others love it, and some hate it. Some Christians never talk about it; some people never stop talking about it. A lot of people throughout the country were using it as a predictor of current events and using it as part of their impetus to get into the Iraq war. People could apply this sort of war against good and evil to almost any situation you were involved with.

FAW: Pagels, author of the acclaimed book The Gnostic Gospels, was one of the first scholars to study ancient scrolls unearthed in Egypt in 1945. What the scholars found is that the Book of Revelation was not written by the author of the Gospel of John but by a different John living on the isle of Patmos off what is now Turkey.

FAW: Pagels, author of the acclaimed book The Gnostic Gospels, was one of the first scholars to study ancient scrolls unearthed in Egypt in 1945. What the scholars found is that the Book of Revelation was not written by the author of the Gospel of John but by a different John living on the isle of Patmos off what is now Turkey.

PAGELS: He seems to be a Jewish prophet who is a refugee from a war in his own country, which was Judea, from Jerusalem, where a war had broken out in 66 to the year 70 when the Romans came in with 60,000 troops and totally destroyed Jerusalem.

FAW: It was, she writes, John’s “cry of anguish.”

PAGELS: This book picks up the language from the prophets and speaks about Rome and the leaders of Rome, the emperors, as a huge bright red dragon with seven heads, seven horns on its head. It was anti-Roman propaganda, because John was devastated by what had happened to his people, what had happened to the city of Jerusalem.

FAW: He writes it in language of dreams and nightmares.

PAGELS: Yes. It was probably dangerous in the Roman Empire to openly express hostility to Rome, so people would have done it in coded language.

FAW: John’s Book of Revelation targeted the Roman Empire as evil. But nearly 300 years later, when the Roman Empire became Christian, a wily and powerful bishop, Athanasius, used the Book of Revelation to strengthen his hold on the Christian movement.

PAGELS: He says well it’s not just about the Roman Empire. This is about me fighting my opponents trying to create the orthodox Catholic Church in the fourth century. So he turns it into a story about Christians against other Christians, and that’s taken up later by Martin Luther against Catholics. It’s taken up by Catholics against Martin Luther. It’s taken up by Catholics against Protestants and Protestants against Catholics, and it keeps on going that way.

PAGELS: He says well it’s not just about the Roman Empire. This is about me fighting my opponents trying to create the orthodox Catholic Church in the fourth century. So he turns it into a story about Christians against other Christians, and that’s taken up later by Martin Luther against Catholics. It’s taken up by Catholics against Martin Luther. It’s taken up by Catholics against Protestants and Protestants against Catholics, and it keeps on going that way.

FAW: And it was Bishop Athanasius who decreed that the revelation written by John of Patmos would be in the Bible even though most bishops would have left it out, says Pagels.

PAGELS: Most of the list we have of what’s supposed to be the New Testament completely leave this book out. It’s just gone. The one person who puts it in is Bishop Athanasius, and he realized that he could take this imagery of the war of good against evil and turn it against his religious enemies.

FAW: In that treasure trove of scrolls found in Egypt in 1945 there was not just one Book of Revelation. There were several, altogether different than the book that got in the Bible.

PAGELS: Most of them aren’t about the end of the world, and they’re not about judging the good and the evil. These other revelation texts have a different vision of the human race, that the same people could be both cruel and compassionate, that we are more complex than that.

FAW: They would not have been as useful for Bishop Athanasius to consolidate the church. That’s why he chose this particular one?

FAW: They would not have been as useful for Bishop Athanasius to consolidate the church. That’s why he chose this particular one?

PAGELS: I think that Athanasius did choose this to consolidate the church and talk about you have to be, you know, orthodox to go up into heaven. Otherwise you fall into the lake of fire. I mean, this had been terrifying images for thousands of years.

FAW: Those images, the four horsemen of the apocalypse and the whore of Babylon—that is the version which resonates even now, largely, says Pagels, because those images can mean whatever a reader wants them to mean.

PAGELS: This book isn’t communicating much that’s cerebral. It’s really about what we hope and what we fear, and it’s as though you take all of your nightmares about plague or destruction or war or torture or natural catastrophe, and you just wrap it into a huge single nightmare, you get the Book of Revelation. But it comes out with hope at the end, so it’s very appealing to people who live in times of huge turmoil.

FAW: I wonder if a reader could come away thinking this book should not be taken as seriously as history has shown it has been taken.

PAGELS: I think you’re right that when you look at a book that’s in the Bible and you start to look at it in historical context, and you say, oh, this person wrote it in that situation, in war, you can say it doesn’t matter as much. It’s not necessarily something that came down from heaven. I’m a historian and that, to me, is an important way of looking at it. It’s not the only way. It’s not the way most religious people look at it. But it seems to me an important way of understanding our tradition.

FAW: Elaine Pagels’ new book, Revelations, may not become a best-seller like The Gnostic Gospels was, but it is already focusing attention on this Princeton professor, who says revelation might not give her comfort but that it does satisfy her curiosity.

PAGELS: I actually find this very compelling, and I am saying why? That’s a question I ask myself. What is it I love about this tradition, this Christian tradition? I wanted to think about how religion works, why people still are very deeply affected by religious language. I wanted to explore that, and this book is a perfect book for that because it’s not about the intellect. It goes straight to the emotions.

FAW: The Book of Revelation—always perplexing and provocative and now seen anew.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Bob Faw in Princeton, New Jersey.

BOOK EXCERPT:

Read an excerpt from REVELATIONS: VISIONS, PROPHECY, AND POLITICS IN THE BOOK OF REVELATION by Elaine Pagels

John’s Book of Revelation appeals not only to fear but also to hope. As John tells how the chaotic events of the world are finally set right by divine judgment, those who engage his visions often see them offering meaning—moral meaning—in times of suffering or apparently random catastrophe. Many poets, artists, and preachers who engage these prophecies claim to have found in the them the promise, famously repeated by Martin Luther King Jr., that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Finally, too, this worst of all nightmares ends not in terror but in a glorious new world, radiant with the light of God’s presence, flowing with the water of life, abounding in joy and delight. Whether ones sees in John’s visions the destruction of the whole world or the dark tunnel that propels each of us toward our own death, his final vision suggests that even after the worst we can imagine has happened, we may find the astonishing gift of new life. Whether one shares that conviction, few readers miss seeing how these visions offer consolation and that most necessary of divine gifts—hope.

Finally, too, this worst of all nightmares ends not in terror but in a glorious new world, radiant with the light of God’s presence, flowing with the water of life, abounding in joy and delight. Whether ones sees in John’s visions the destruction of the whole world or the dark tunnel that propels each of us toward our own death, his final vision suggests that even after the worst we can imagine has happened, we may find the astonishing gift of new life. Whether one shares that conviction, few readers miss seeing how these visions offer consolation and that most necessary of divine gifts—hope.

But we have seen that the story of this book moves beyond its own pages to include the church leaders who made it the final book in the New Testament canon, which they then declared closed, and scriptural revelation complete. After Athanasius sought to censor all other “revelations” and to silence all whose views differed from the orthodox consensus, his successors worked hard to make sure that Christians could not read “any books except the common catholic books.”

Orthodox Christians acknowledge that some revelation may occur even now, but since most accept as genuine only what agrees with the traditional consensus, those who speak for minority—or original—views are often excluded.

Left out are the visions that lift their hearers beyond apocalyptic polarities to see the human race as a whole—and, for that matter, to see each one of us as a whole, having the capacity for both cruelty and compassion. Those who championed John’s Revelation finally succeeded in obliterating visions associated with Origen, the “father of the church” posthumously condemned as a heretic some three hundred years after his death, who envisioned animals, stars, and stones, as well as humans, demons, and angels, sharing a common origin and destiny. Writings not directly connected with Origen, like the Secret Revelation of John, the Gospel of Truth, and Thunder, Perfect Mind, also speak of the kinship of all beings with one another and with God. Living in an increasingly interconnected world, we need such universal visions more than ever. Revering such lost and silenced voices, even when we don’t accept everything they say, reminds us that even our clearest insights are more like glimpses “seen through a glass darkly” than maps of complete and indelible truth.

Many of these secret writings, as we’ve seen, picture “the living Jesus” inviting questions, inquiry, and discussions about meaning—unlike Tertullian when he complains that “questions make people heretics” and demands that his hearers stop asking questions and simply accept the “rule of faith” And unlike those who insist that they already have all the answers they’ll ever need, these sources invite us to recognize our own truths, to find our own voice, and to seek revelation not only past, but ongoing.

From “Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation” by Elaine Pagels (Viking, 2012)