In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Prosecutorial Misconduct

TIM O’BRIEN, correspondent: Remember the infamous Duke rape case? Where a prosecutor accused three members of the school’s lacrosse team of rape and knowingly withheld evidence that would have cleared them? We like to think of such cases as aberrations, but in recent years, several high profile Justice Department cases have been thrown out because of similar misconduct.

Joseph DiGenova, the former United States Attorney for the District of Columbia says Justice Department prosecutors routinely withhold evidence that could be helpful to the defense and rarely is anything done about it.

JOSEPH DIGENOVA: I’m a former United States Attorney. I locked up a lot of people. I believe in the Department, I believe in its mission. But the Department is in real trouble. This is serious business. These career prosecutors believe that nobody can touch them. Nobody! That’s a very dangerous thing in a free society and the Stevens case proves it in spades.

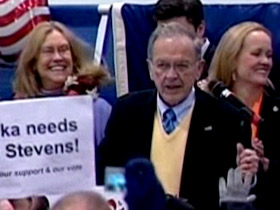

O’BRIEN: The “Stevens case” is the botched prosecution of former Alaska Senator Ted Stevens, one of the longest serving and most influential members of Congress. The Justice Department had accused the Senator of accepting home improvements from an oil executive and then misleading Congress about it.

O’BRIEN: The “Stevens case” is the botched prosecution of former Alaska Senator Ted Stevens, one of the longest serving and most influential members of Congress. The Justice Department had accused the Senator of accepting home improvements from an oil executive and then misleading Congress about it.

SEN. LISA MURKOWSKI (R-AK): Few prosecutions cut as close to the relationship of the American people to their government as this one did. If the Justice Department is going to allow a case involving a sitting Senator seeking re-election to go to a jury weeks before that Senator’s general election, it must be absolutely certain that the defendant’s rights were meticulously observed.

O’BRIEN: What is now certain in the Stevens’ case is that the Senator’s rights were not observed at all. He was convicted and, eight days later, narrowly lost his bid for re-election, altering the balance of power in the U.S. Senate. But Stevens might well have been acquitted—and re-elected—had prosecutors not repeatedly withheld critical evidence.

The trial judge, Emmit Sullivan, berated government prosecutors, saying “In nearly 25-years on the bench, I’ve never seen anything approaching the mishandling and misconduct that I’ve seen in this case.”

The Senator’s attorney, Brendan Sullivan, is famous for winning cases by uncovering the misconduct and ethical violations of the accusers.

BRENDAN SULLIVAN (Attorney for Senator Ted Stevens): When prosecutors get into the heat of battle, something takes over the competitive spirit—their reputational implications—and they want to win at all costs. They then begin to think if I lose this case it will be very bad for me professionally because I’ll be known as the lawyer, the prosecutor, who lost a case that may be very visible.

BRENDAN SULLIVAN (Attorney for Senator Ted Stevens): When prosecutors get into the heat of battle, something takes over the competitive spirit—their reputational implications—and they want to win at all costs. They then begin to think if I lose this case it will be very bad for me professionally because I’ll be known as the lawyer, the prosecutor, who lost a case that may be very visible.

O’BRIEN: A 1963 Supreme Court case called Brady versus Maryland requires prosecutors to turn over to the defense any material evidence that might be helpful.

That case involved John Brady, convicted and sentenced to death for murder even though a co-defendant had actually confessed to the crime. Prosecutors never shared that confession with Brady’s lawyers.

In throwing out Brady’s death sentence, Justice William O. Douglas alluded to the inscription over the door to the Attorney General’s office at the Department of Justice: “The United States wins its point whenever justice is done its citizens in the courts.” The idea: the goal is “justice,” not merely winning convictions.

For some prosecutors, that is a tough pill. Assisting those they believe to be guilty goes against the grain. Whatever the motivation in the Stevens case, the end result was a black-eye for the Justice Department.

Attorney General Eric Holder had only been in office two months, but he found the prosecution’s case so riddled with misconduct, he asked the court to dismiss all charges, and has been widely praised for doing so. Holder declined our request for an interview and the Department would not provide any other spokesman to speak on the record. But the Department could not decline a call from the Senate Judiciary Committee which has been looking into the Stevens case and all of its ramifications.

Deputy Attorney General James Cole told senators the case has prompted a department-wide training program to educate all U.S. prosecutors about their obligations to share exculpatory evidence with the defense.

JAMES COLE (Deputy U.S. Attorney General): …to a point where everybody, every supervisor, every trial attorney is required every year to take the training. As the Deputy Attorney General, I am required to take this training every year.

JAMES COLE (Deputy U.S. Attorney General): …to a point where everybody, every supervisor, every trial attorney is required every year to take the training. As the Deputy Attorney General, I am required to take this training every year.

O’BRIEN: Committee Chairman Pat Leahy is himself a former prosecutor.

SEN. PATRICK LEAHY (D-VT): In the Stevens case, they seemed to be driven by “let’s get a conviction, at all costs” and somehow justice, the question of justice, just gets lost.

COLE: I think it should be noted, again, the failures in this receive a lot of attention, but they’re actually very rare.

SEN. MIKE LEE (R-UT): Doesn’t the very nature of the Brady rule, and the violation of the Brady rule, make it somewhat difficult to detect by its very nature?

COLE: Well, it can be.

O’BRIEN: No one can know how common Brady violations are. Some defense lawyers claim they happen all the time. But over the years, some prosecutors have treated the Brady decision, and the obligations it imposes, as a game.

In one of the cases stemming from the collapse of the energy giant Enron, the government agreed to provide everything it had: 80-million pages, without any guidance as to what might be important or otherwise helpful.

The Brady decision requires prosecutors to turn over only evidence that is “material”—a judgment made unilaterally by the prosecutor. And if the prosecutor gets it wrong, who’s to know?

SULLIVAN: Right now, the standard is a prosecutor says to himself, “Well, this information that I have, is it really material to the defense?” Can you imagine such a standard? Here’s your adversary deciding whether it’s material to your defense. They don’t think defensively. They don’t know what your defense is, and yet they’ve got to make that decision.

SULLIVAN: Right now, the standard is a prosecutor says to himself, “Well, this information that I have, is it really material to the defense?” Can you imagine such a standard? Here’s your adversary deciding whether it’s material to your defense. They don’t think defensively. They don’t know what your defense is, and yet they’ve got to make that decision.

SEN. MURKOWSKI: S2197 would eliminate the materiality requirement as a matter of statutory law.

O’BRIEN: Alaska’s Senator Murkowski has introduced legislation that would require that any evidence that can help the defense be turned over. But the Justice Department opposes that, Deputy Attorney General Cole testifying no new laws are needed.

COLE: …because the problem was not what the rules were that were in place. The problem was that the prosecutors in the case didn’t follow the rules.

O’BRIEN: Cases get reversed when prosecutors don’t follow the law, but very little ever happens to the offending prosecutor. Notwithstanding a finding of “reckless professional misconduct” in the Stevens case, only two prosecutors were punished—one suspended for 45 days, another for 15 days.

Sullivan’s law firm issued a written statement calling the sanctions “pathetic” and “laughable” and conclusive proof that “the Department of Justice is not capable of disciplining its prosecutors.”

Recent history might seem to bear that out. An investigative report by USA Today identified more than 200 cases thrown out by judges as a result of misconduct or ethical violations, but only one of those offending prosecutors was removed.

Prosecutors—whether at the Justice Department or down at the county courthouse—are the most powerful actors in the criminal justice system. They decide who gets charged and what they are charged with, life and death decisions in some cases. And when they themselves violate the law, when they withhold evidence or even fabricate a case, they cannot be sued. They have absolute immunity for their official acts.

SULLIVAN: They can intentionally engage in wrongdoing, obtain a conviction, put a person in jail for decades and when caught, there’s no lawsuit that can be brought by that individual person who’s just lost a decade or two of their lives.

O’BRIEN: Senator Stevens won his fight with the Justice Department, but lost his life 16 months later in a plane crash. The Justice Department’s prosecution, and how it backfired, will surely be part of his legacy.

But will it make any difference in how prosecutors go about their work? That will take better education and training, as Attorney General Holder has promised. It will also require accountability, meaningful sanctions for those prosecutors who themselves fail to follow the law.

In the end, it is a matter of trust, which, as the Department of Justice is now learning, can be elusive. Once it’s gone, it’s difficult to get back.

For Religion and Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Tim O’Brien in Washington.