In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Islamic Art Galleries

DR. SHEILA CANBY (Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Islamic Art): Overall, the collection has twelve thousand objects; and we are showing twelve hundred.

There are motifs that you find across a very wide geographic spread, and that wouldn’t have happened if those regions hadn’t been unified by a single religion, being Islam.

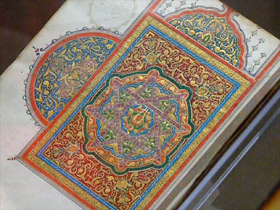

The use of the Arabic script, of course, spread, as the religion spread. They reverse it, they do mirror writing, tiny writing, huge writing.

The written word in Islam is of absolute paramount importance. And the act of copying a Quran is an act of devotion, religious devotion.

A mihrab is, of course, the central focus in a mosque. It’s what people face when they pray and in a mosque would be lined up so that the people facing it are facing the direction of Mecca.

A mihrab is, of course, the central focus in a mosque. It’s what people face when they pray and in a mosque would be lined up so that the people facing it are facing the direction of Mecca.

We have glass mosque lamps. We have one or two ceramic ones as well. They were probably made in sets to be used in mausoleums and madrassas and mosques.

Our newest gallery is our Moroccan court, which was built here over a six-month period by a group of craftsmen from Fez. What it is is an adaptation of the type of courtyard that one finds in several madrassas, religious schools or seminaries, in Fez. But, you know, our court is just tiny by comparison to those, so the challenge really was that we had to design it in such a way that they could kind of shrink but keep the proportions right. The tile panels are actually inspired by a tile panel in Alhambra.

One of the stories we wanted to tell, really, was about the complexity of society in Spain while it was still under Muslim control, and so we have actually two Hebrew manuscripts. The Hebrew Bible is fascinating because it has a page with what looks like geometric designs. But then if you look closely you realize that all these geometric designs are made from micro-writing, and in the same case we have pages from a Quran that was written in micro-writing. So not only were the geometric designs being shared and used by people of different faiths, but also the whole idea of this tiny writing seems to have appealed to both Muslims and to Jews in Spain.

We have a recent acquisition, actually, which is a painting that depicts the goddess Bhairavi Devi, and she sits with the god Shiva in a sort of charnel ground. It’s a Hindu subject; it’s a ferocious Hindu subject, in fact, and it has this goddess whose eyes are just drilling the viewer. So it just shows, especially in a place like India, what a completely complex society in terms of religion it was at the time.

We have a recent acquisition, actually, which is a painting that depicts the goddess Bhairavi Devi, and she sits with the god Shiva in a sort of charnel ground. It’s a Hindu subject; it’s a ferocious Hindu subject, in fact, and it has this goddess whose eyes are just drilling the viewer. So it just shows, especially in a place like India, what a completely complex society in terms of religion it was at the time.

Muhammad is depicted in certain contexts. There were illustrated histories which show the life of Muhammad. Then in the poetic context, really in mystical poetry, we find depictions of this Mirage, the Night Journey, and he’s riding on a human-headed horse up to heaven. These were images that were painted by Muslim painters for Muslim patrons. So it was completely within a Muslim context that they were done. There was nothing untoward at all about them.

What I would hope is that people would understand that although the religion infuses all of these lands and these historical periods that regions were individual, and regions had particular styles. And also the commonality with mankind, which is that we all have—we all eat and have bowls to eat from, we all, you know—there are so many things that are common to all of us, and to think of things in that way, I think, humanizes the religion and humanizes the objects to people who are not familiar with it.