In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

The UN and Muslim Protests

BOB ABERNETHY, executive editor and host: As protests against an anti-Islam video continued in many parts of the world, debates over tolerance, free speech, and religiously motivated violence were front and center at the opening session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York.

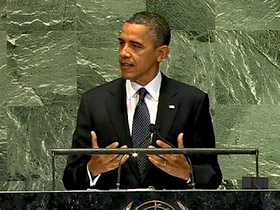

In a strong speech, President Obama again condemned the video as an insult to Muslims and to all Americans. But he said America rejects attempts to restrict even speech that insults religion.

President Obama at UN: “We do so because given the power of faith in our lives, and the passion that religious differences can inflame, the strongest weapon against hateful speech is not repression, it is more speech: the voices of tolerance that rally against bigotry and blasphemy, and lift up the values of understanding and mutual respect.”

ABERNETHY: The president also called on world leaders to speak out forcefully against extremism.

ABERNETHY: The president also called on world leaders to speak out forcefully against extremism.

President Obama at UN: “That brand of politics, one that pits East again West, South against North, Muslim against Christian, Hindu and Jew, cannot deliver the promise of freedom.”

ABERNETHY: But many Arab and Muslim leaders renewed their calls for a UN resolution that would ban defamation of religion. Egypt’s new president Mohammed Morsi said his country respects freedom of expression, but, he added “not the freedom of expression that deepens ignorance and disregards others.”

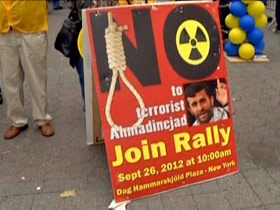

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad once again generated controversy in a speech that accused what he called “uncivilized Zionists” of threatening war against his country. Protesters outside the UN denounced Ahmadinejad’s continued anti-Semitic language. Many Jews were particularly upset that his speech fell on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the holiest day on their calendar.

Meanwhile, several world leaders urged the UN to do more to end the conflict in Syria. Many warned of a looming crisis facing the nearly 300,000 Syrian refugees who have fled to neighboring countries. UN humanitarian officials called for more international aid and said if the fighting doesn’t end, the number of refugees could rise to 700,000 by the end of this year.

Meanwhile, several world leaders urged the UN to do more to end the conflict in Syria. Many warned of a looming crisis facing the nearly 300,000 Syrian refugees who have fled to neighboring countries. UN humanitarian officials called for more international aid and said if the fighting doesn’t end, the number of refugees could rise to 700,000 by the end of this year.

In addition to emergency aid, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said a “top priority” for the international community should be promoting sustainable development that will provide long-term help for poor countries.

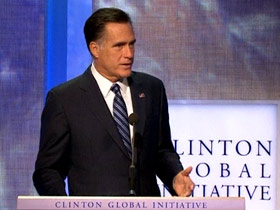

Governor Mitt Romney sounded similar themes at former President Bill Clinton’s Global Initiative, which took place at the same time as the General Assembly meetings. Romney urged a reexamination of temporary foreign aid.

Governor Mitt Romney: It can employ some people for a time, but it can’t sustain an economy, not for the long term. It can’t pull the whole cart if you will because at some point, the money runs out. But an assistance program that helps unleash free enterprise can create enduring prosperity.”

ABERNETHY: The calls at the UN for outlawing offensive speech produced strong defenses of such speech not only by President Obama but also from leaders in the American Muslim community.

ABERNETHY: The calls at the UN for outlawing offensive speech produced strong defenses of such speech not only by President Obama but also from leaders in the American Muslim community.

I want to explore that with Kim Lawton, managing editor of this program, and Haris Tarin, director of the Washington office of the Muslim Public Affairs Council.

Haris, how are you trying to persuade, how are American Muslims trying to persuade other Muslims around the world that putting any kind of limit on free speech is dangerous?

HARIS TARIN (Muslim Public Affairs Council): Well, I think the first way we’re trying to convince fellow Muslims of this is the fact that the idea of free speech is a foundational part of the Quran itself. We don’t only believe that in terms of Americans and our belief in the Constitution , but the Quran challenges folks to engage in dialogue and in discourse, challenges people of the same faith and various different faiths, as well. So it’s foundational to the text of Islam, we believe. The Quran actually records insults to the Prophet Muhammad himself and challenges people to engage in that discourse. So I think it’s foundational not only to the Constitution but to our sacred texts, as well.

ABERNETHY: Are you getting anywhere with that argument?

TARIN: I think we are. We are. We’ve put out several videos in various languages, in Dari, in Pashto, Arabic, Somali, and they’ve gotten close to a million views by folks in the Muslim world, and we’ve gotten a very positive response, especially from young people who went out on to the streets of Cairo, of Tunis, of Libya to ask for their right for free speech, to begin with.

TARIN: I think we are. We are. We’ve put out several videos in various languages, in Dari, in Pashto, Arabic, Somali, and they’ve gotten close to a million views by folks in the Muslim world, and we’ve gotten a very positive response, especially from young people who went out on to the streets of Cairo, of Tunis, of Libya to ask for their right for free speech, to begin with.

KIM LAWTON, managing editor: I’ve been struck also, I’ve been following this debate for a while, and it’s not just Muslim-majority countries that are pushing for these restrictions on defamation against religion, although they’ve been at the forefront of it, but it’s an idea that also has traction in some African and Latin American countries, where people have this idea that religion is somehow different and that you shouldn’t insult religion and in fact, you know, even in Western Europe, there’s some—already it’s against the law to deny the Holocaust in many European countries. So our notion of free speech, especially when it comes to religion, is not shared around the world.

ABERNETHY: But is it changing?

TARIN: I think it is changing. I think, as the world becomes smaller, we live in a globalized world, and people are realizing, as President Obama said in his UN speech, that someone with a phone camera can really cause a stir around the world, and so that we’ve got to be able to adjust, we’ve got to able to have a discourse and dialogue when it comes to difficult issues like this rather than take the streets and commit acts of violence.

LAWTON: I found it interesting American Muslims seem to be speaking to two audiences in effect, because on one hand you’re speaking to Muslims around the world, but on the other hand you’re also speaking to American societies and trying to say not all Muslims are like the people who are in the streets doing violence. I mean, has that been a challenge for you all?

LAWTON: I found it interesting American Muslims seem to be speaking to two audiences in effect, because on one hand you’re speaking to Muslims around the world, but on the other hand you’re also speaking to American societies and trying to say not all Muslims are like the people who are in the streets doing violence. I mean, has that been a challenge for you all?

TARIN: It is a difficult balancing act, but I think people realize that the majority of people who are out on the streets, they were a very small number, and amongst the small number the ones who committed acts of violence were even smaller. As we were saying earlier, in Libya people came out in the thousands in support of the ambassador, in support of our country.

ABERNETHY: But there’s also some politics in here, isn’t there? I mean, hardliners in some of these countries, are they not encouraging some of the violence in order to put pressure on these new, fragile governments?

TARIN: They are.

ABERNETHY: To become hardline themselves.

TARIN: Absolutely, absolutely. These countries are nascent democracies and hopefully democracies. There’s a vacuum of power and a vacuum of authority in many of these societies, so extremists are taking advantage of this vacuum in power and authority and, unfortunately, they don’t want to see a free, democratic Libya or Egypt or Tunisia or Pakistan. They want to see an extremist vision for their societies, so they’re trying to take advantage of this vacuum in power, and what we have to do is stand on the side of the majority to ensure that we marginalize the extremists in those societies and also the extremists who put the film together and promoted the film, as well.

LAWTON: I noticed that your organization, in a statement, really did call on the Muslim community to also examine the role of extremism within the Muslim community, and certainly that is a theme that President Obama talked about this week as well in the UN speech, where he was a little more forthright than he has been in the past in calling on nations to, and leaders of nations, to deal with extremism in their midst.

ABERNETHY: Thanks to Kim Lawton and to Haris Tarin for being with us. Thanks.

TARIN: Thank you.