In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

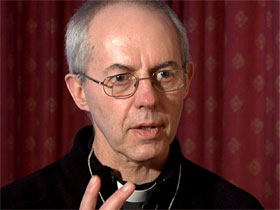

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby

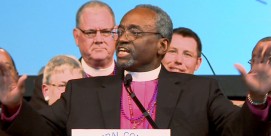

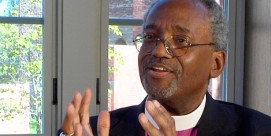

KIM LAWTON, managing editor: In a ceremony filled with pomp and pageantry, Justin Welby was installed as the new spiritual leader to nearly 80 million Anglicans around the world. The 57-year-old Welby is a former oil company executive who became a priest in his mid-30s. He had been a bishop for just a year when he was chosen for the Anglican Communion’s highest post. One of his toughest challenges may be helping the Communion stay together amid profound differences over theology, gender, and sexuality. The Anglican body has more than 40 separate branches, including the Church of England, the Episcopal Church in the US, and numerous churches across Africa, Asia, and South America.

ARCHBISHOP JUSTIN WELBY (Archbishop of Canterbury): We are struggling with very, very significant divisions, different ways of looking at the world coming out of our context, coming out of our history, and learning how we deal with those differences, which are of themselves valuable things, is really significant.

LAWTON: Welby told me as archbishop he intends to promote reconciliation as one of his top priorities.

WELBY: It is the key theological concept for Christian faith, reconciliation with God and the breaking down of barriers between people. And therefore for me, I have this sense that part of the church’s role is to be reconciled reconcilers.

LAWTON: He has already created a new position on his staff at Lambeth Palace, Director for Reconciliation, and appointed Canon David Porter from the historic Coventry Cathedral to help oversee his agenda.

CANON DAVID PORTER (Coventry Cathedral): I see my work in conflict areas, in helping people deal with differences, and to celebrate the diversity as a profound expression of the good news of Jesus and as a profound expression of my faith in practice.

LAWTON: But it will be no easy task. For the past decade, the Communion has been in turmoil after the Episcopal Church consecrated an openly gay bishop and approved blessings for same-sex unions. Some African and Asian jurisdictions accused the US church of heresy. Many conservative American congregations have broken away from the Episcopal Church and aligned themselves with African Anglicans. There have been a series of contentious lawsuits over church property, and some congregations are now worshiping in schools. Bitterness still prevails in many quarters throughout the Communion. Welby concedes in such circumstances it’s difficult to even think about reconciliation.

WELBY: Reconciliation is extraordinarily painful for those involved in the conflict.

LAWTON: Some people have a fear maybe that when one talks about reconciliation, what they might really mean is just papering over differences in order to…

WELBY: Yes, absolutely.

LAWTON: …just get along. You know, the most important thing is that we get along.

WELBY: Oh, fuzzy wuzzy tolerance, sort of fluffy, where it would all be nice if we were nice to each other sort of rubbish. Yes, that’s not at all what we’re talking about. It’s not a magic wand that you wave over people, and suddenly everyone’s happy, and when they are I’m usually slightly suspicious.

LAWTON: True reconciliation, Welby says, requires courage, honesty, and integrity.

WELBY: It is the process of enabling, of making yourself sufficiently transparent that people trust each other, of putting your most valued and passionate beliefs out for them to be examined, attacked, and then finding a way to love the person with whom you are dealing, quite probably not agreeing with each other, but disagreeing in love.

LAWTON: On two of the most controversial issues, Welby opposes gay marriage, and he supports allowing women to be bishops. He acknowledges many of the current divisions in the Communion stem from differing views of how to interpret scriptural truth.

WELBY: We need a certain integrity about where we get our truth from. Now I’m not saying that truth is up for grabs. There are truths. I believe passionately in that. There are things I believe passionately are deeply wrong.

LAWTON: But, he says, he sees another need as well.

WELBY: The need for not only theological orthodoxy, but relational orthodoxy. In other words, right relationships as well as right understandings and ideas.

LAWTON: Welby also wants to emphasize peacemaking in conflicts outside the Church, such as in places like Nigeria, where he has traveled many times.

WELBY: The Church is there in a sense as sometimes the least dysfunctional part of a conflicted society, destructively conflicted society, but very often is the only functional part. And that’s where we bring a passion for reconciliation, for enabling people to continue their dispute without violence.

LAWTON: Over the next few months, the new archbishop plans to spend time listening to members of his flock around the world. He hopes to soon visit the US.

WELBY: I really genuinely believe that the United States remains one of the world’s great hopes and potentials for development and peace under God. And so that’s my prayer for the States is continue to find this radical and exciting location that’s been yours for 230 years and challenge us.

LAWTON: Welby is optimistic about the future of the Anglican Communion, mostly, he says, because he believes in the grace of God.

WELBY: When God is left out of it then all we’re left with is our own ideas, and we defend those to the death and preferably the death of the other. When God is in the middle of it, there is a transforming power and presence.

LAWTON: And he says he’ll be praying for that grace every day.

I’m Kim Lawton in the UK.

BOB ABERNETHY, host: Kim, welcome back. You did a great job.

KIM LAWTON: Thanks.

ABERNETHY: Justin Welby says he’s going to try to reconcile things in the Anglican Communion. Does he really have power enough to do something there?

LAWTON: Well that’s the big question. The Archbishop of Canterbury doesn’t have, you know, a lot of authoritative power to make things happen. He has the moral authority to set a tone which is what he’s trying to do, set a tone for dialogue, peacemaking but the divisions are really, really strong. Anglicans have long talked about being unified amid diversity but the question is, is that diversity, are those differences so great that unity is just not possible. And also the level of acrimony, especially here in the U.S. that we’ve seen is still very, very strong between some of the breakaway churches and the official Episcopal Church and attempts at peace building have not been successful.

ABERNETHY: And let’s turn to Pope Francis. You got sort of close to him.

LAWTON: Sort of.

ABERNETHY: What were your impressions?

LAWTON: Well, I was, I was in a meeting with several thousand other journalists. We got to “meet” him and certainly I saw what a lot of people talk about, that quiet warmth. He doesn’t have a big personality. He’s not jovial in that sense. But there’s a warmth that really comes through. He connects with people that he’s with. He went off his text, his script, many times in his talk and made some jokes with the journalists and another interesting thing I found, he, instead of doing a tradition blessing with the cross, making the sign of the cross, he acknowledged that many people in the room weren’t Catholics and probably weren’t even believers so he said I’ll pray for you in my heart out of respect. That was something interesting from a pope.

ABERNETHY: Many people say that the number one thing that Pope Francis needs to do is something about the sex abuse scandal.

LAWTON: I hear that a lot, from U.S. Catholics in particular. They want to see something from him. He’s said in the past that he has a zero tolerance policy. They want to see him embrace that as pope. I hear a lot of Catholics talking about there are changes he could make in the bureaucracy. He could meet with victims. He could meet with victims’ advocacy groups. So they are hoping he really does take a firm stand on that issue.

ABERNETHY: There have been several stories and opinion columns about whether, when he was in Argentina, he did enough to stand up to a very oppressive, cruel government. Is that going anywhere?

LAWTON: You know, who knows what may come out. Certainly there have been questions, there have been questions for a long time now about that. People say he at the very least didn’t stand up as much as he could have. There were some suggestions that maybe he in some way created or enabled some of the persecution but those seem to, other people have come out and said no that’s not the case.

ABERNETHY: And very quickly, many people hope for what they call evangelization in this papacy. Quickly, what does that mean?

LAWTON: Well for Catholics they would like to see their faith spread. And so whether you’re talking moderate and liberal Catholics hope that Francis’s emphasis on issues like the environment and the poor, things that have always been important to the church but maybe not emphasized, maybe that will appeal to some people. Conservatives hope that his pastoral demeanor, his clear love of God, of Jesus, that maybe that will be appealing and help bring Catholics back to the church.

ABERNETHY: Kim Lawton, many thanks.