In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Birmingham and the Children’s March

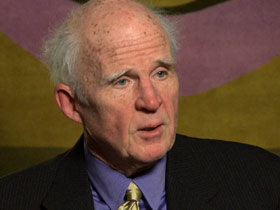

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: At the Civil Rights Institute in Birmingham, Alabama, local students are on a field trip, learning how 50 years ago, kids around their age played a pivotal role in the struggle against segregation. One of them was Freeman Hrabowski, who is now president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He was 12 at the time and a math whiz.

FREEMAN HRABOWSKI III (Univ. of MD, Baltimore Co.): I was not a courageous kid. I did not get into fights. The only thing I would attack was a math problem. And so, this was not about courage at all, it was about having a dream of a better day.

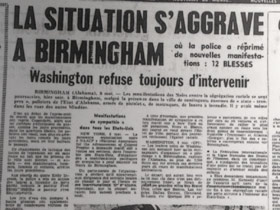

LAWTON: In 1963, Birmingham was considered one of the most segregated places in the US.

HRABOWSKI: Children knew, children of color were well aware we were considered second class.

LAWTON: Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Birmingham in January 1963 to support local efforts to end segregation through non-violent protests. But the campaign didn’t take off as he had hoped.

TAYLOR BRANCH (Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author): He prepared for three months and started the demonstrations in April. They fizzled quickly, nothing went according to plan.

LAWTON: While King was trying unsuccessfully to inspire adults to march and get arrested, civil rights leaders including Rev. James Bevel and Dorothy Cotton were holding special meetings for Birmingham elementary and high school students.

DOROTHY COTTON (Civil Rights Leader): We knew that they were curious about what was going on in their town. We were not there to recruit them. They just started hanging around, coming around and it swelled.

BRANCH: When Dr. King was about to retreat from Birmingham, the people running the children’s workshops said, “Don’t do it because we’re out of people. I got plenty of foot soldiers.”

LAWTON: It was a controversial prospect. Birmingham’s police commissioner Bull Connor was notorious for his efforts to stop any protests. Movement leaders argued among themselves about whether this was the right strategy.

REV. VIRGIL WOOD (Civil Rights Leader): Dr. King was severely criticized for allowing the children to be involved, but the children insisted themselves. The children were their own self-initiators of their own freedom. They said, “This is our future and we want to help shape it.”

LAWTON: Rev. Carolyn McKinstry was 14 and volunteering in her church, Sixteenth Street Baptist, when she overheard the ministers calling on children to march.

REV. CAROLYN MCKINSTRY (Author, While the World Watched): It was such an excitement in the air I knew I wanted to be part of it.

LAWTON: She didn’t tell her parents, especially her strict father, about her decision.

MCKINSTRY: I know if I had asked he would have said no.

LAWTON: Hrabowski came from an educated middle class family. He says his parents dragged him to a civil rights meeting, and he was sitting in the back of the church doing his math homework when he heard King give the call.

HRABOWSKI: And I’ll never forget listening, but doing the math and hearing a man say, if the children participate in this demonstration, in this peaceful demonstration, all of America will see that even children understand the difference between right and wrong and that children want the best possible education.

LAWTON: Afterward, he told his parents he wanted to march.

HRABOWSKI: And they said, absolutely not. And I was very upset, and I said to them, “Then you guys are hypocrites. You told me to go and listen to the minister. I did. I want to do what he suggested and you’re saying no.” But at that time you did not say that to your parents. So my father said very calmly, “Go to your room.”

LAWTON: He says the next morning, his parents came in and sat on both sides of his bed.

HRABOWSKI: I could tell they had been crying. I’d never seen my parents cry. And they said they’d been praying all night. And they said this to me: “It wasn’t that we didn’t trust you. We simply didn’t know who’d be responsible for you and how you’d be treated if you were placed in jail.” And so they thought about it and they said, “But we have decided to leave it in God’s hands.”

LAWTON: Before they could march, the young people were trained about the importance of non-violence.

MCKINSTRY: We were told what to expect when we marched, if we did encounter the police. They might hit you, they might spit on you, they will have dogs and billy clubs but the only appropriate response ever is no response, or a prayerful response.

LAWTON: On Thursday May 2nd, “The Children’s March” began. Students left their classrooms mid-day and gathered in Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. They came out marching and singing, row after row after row of them, some as young as six years old. Waiting police arrested them for parading without a permit, but the kids kept coming, and when the paddy wagons were full, the police had to get a school bus to take them all away. Nearly a thousand children had signed up to march, and more than 600 were taken into custody on that day.

LAWTON: As hundreds and hundreds more children showed up to demonstrate and face possible arrest, Bull Connor was anxious to restore order. He instructed his forces to bring out the fire hoses and the dogs.

Some of the most shocking confrontations happened in Kelly Ingram Park, across from the church, where monuments to the marchers now stand. Officials aimed the water hoses full blast at the marching children. McKinstry was among those hit.

MCKINSTRY: The water came out with such tremendous pressure and, uh, it’s a very painful experience, if you’ve never been hit by a fire hose and I thought, whoa. You know, I got knocked down and then we found ourselves crouching together and trying to find something to hold onto. People ran, people hid, people hugged buildings or whatever they could to keep the water hoses from just…just knocking them here and there.

LAWTON: Then, bystanders watched in horror as the police used dogs to try to control the crowd. News reporters captured images of young people being attacked by the German Shepherds. The marching, and the arrests, went on for several days. Energized by the children, adults soon joined in.

COTTON: People felt, they felt it and their actions and their involvement came from that feeling that we were on to something that needed, that was right and that was to change this society.

LAWTON: Hrabowski was in a group of children who marched to city hall.

HRABOWSKI: The police looked mean, it was frightening. We were told to keep singing these songs and so I’m singing, [sings] I ain’t gonna let nobody turn me round, keep on a walking, keep on a talking, marching on to freedom land. And amazingly the other kids were singing and the singing elevates when you can imagine hundreds of children singing and you feel a sense of community, a sense of purpose.

LAWTON: He says he had a direct confrontation with Connor.

HRABOWSKI: There was Bull Connor, and I was so afraid, and he said, “What do you want little nigra?” And I mustered up the courage and I looked up at him and I said, “Suh,” the southern word for sir, “we want to kneel and pray for our freedom.” That’s all I said. That’s all we wanted to do. And he did pick me up, and he did, and he did spit in my face, he really…he was so angry.

LAWTON: Hrabowski was arrested, and like hundreds of other children, held for five days. When the jails got full, the kids were held in the fairgrounds.

HRABOWSKI: I will never forget, Dr. King came with our parents…outside of that awful place. We’re looking out at them, if you can imagine children encaged…it was, it was worse than prison. It was like being treated like little animals, it was awful, crowded, just awful. And he said, what you do this day will have an impact on children who’ve not been born and parents were crying, and we were crying, and we knew the statement was profound, but we didn’t fully understand.

LAWTON: News reports and pictures of what was happening in Birmingham were transmitted around the world. According to Pulitzer Prize winning author Taylor Branch, those reports had a dramatic impact on public opinion.

BRANCH: Millions of Americans who had been seeing demonstrations for years and saying, “Well, there’s something wrong about that and we should do something but it’s not for me, it’s for somebody else,” that broke down those emotional barriers when they saw those children suffering it and millions of people said, “I need to do something about this.”

LAWTON: Branch says the children’s march touched him personally as well.

BRANCH: I was 16. And doing my best to avoid the fearful civil rights movement and when I saw the pictures of those kids half my age singing songs, just like the ones I sang in church, marching into those dogs and fire hoses it had a tremendous effect on me.

LAWTON: Upset about the image of their city, white leaders negotiated a plan with movement leaders to start ending segregation. The Kennedy Administration was also prompted into action and on June 11th, citing the events in Birmingham, President Kennedy announced his intention to introduce new federal civil rights legislation.

MCKINSTRY: It led me to believe, especially after the laws were changed, that there were many things that were worth fighting for.

LAWTON: McKinstry, who became a Baptist minister, continued to fight for civil rights. And today, she works to keep the story of the struggle alive.

MCKINSTRY: It is disappointing to me when I meet people, young people especially, whatever culture they are, and they don’t know the story. We’ve been in some very difficult places, but we’ve come a long way, and we continue to grow and to learn.

LAWTON: Hrabowski says in his work with students, he also continues to draw on the lessons he learned in the Children’s March, lessons, he says, about the power of community, discipline and faith.

HRABOWSKI: The message is this, the world doesn’t have to be the way the world is. That good people can act and the world can be better and so can we.

LAWTON: I’m Kim Lawton in Birmingham.