In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

- Moral Questions on Syria Strikes, Sister Joan Chittister, India’s Jains

- Moral Questions on Syria Strikes

- Sister Joan Chittister

- Sister Joan Chittister Extended Interview

- Sister Anne Wambach Extended Interview

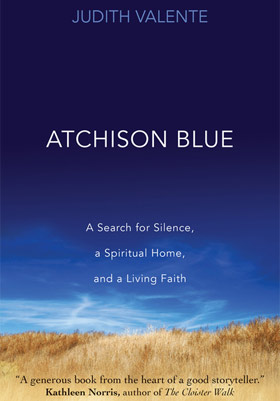

- Book Excerpt: Atchison Blue: A Search for Silence, a Spiritual Home and a Living Faith

- India’s Jains

Book Excerpt: Atchison Blue: A Search for Silence, a Spiritual Home and a Living Faith

Read an excerpt from R&E correspondent Judy Valente’s new book, Atchison Blue: A Search for Silence, a Spiritual Home and a Living Faith (Sorin Books, Ave Maria Press, 2013), and revisit her 2009 story on the Benedictine sisters at Mount St. Scholastica and her 2013 profile of Sister Joan Chittister:

The Work of God

by Judith Valente

A peculiar calm accompanies the hours just before dawn. It is a wordless quiet known to the cop returning home from a midnight shift, the schoolboy delivering morning papers, the short-order cook opening up for breakfast. And monastic men and women at prayer.

At the monastery, Morning Praise begins at 6:30 just as light cracks open on the horizon, making early risers of even habitual night owls like myself. From the guesthouse where I am staying, I set out for the chapel. Stars light my way—the baton of Orion’s Belt, the distant flare of Sirius. Morning Praise. More often than not, my days begin with angst, not praise—fear that I won’t finish the work that awaits me or that I won’t do it well enough. Smoke billows from the nearby stacks of the Midwest Grain Products plant, a giant still in the middle of Atchison, cooking up the base contents of whiskey. The roasting grain fills the air with a pleasant aroma, like baking bread.

At this time of morning, the chapel’s Atchison blue windows form dark outlines. The sisters file in one by one. The younger ones sprint; the older ones lean on walkers or canes. They take their places in stalls facing one another. It is nearly impossible not to make eye contact with others in the community. At home, I have the luxury of avoiding people I find difficult. I simply freeze them out. But here, you daily face the people you live with. I imagine how hard it would be to sit across from someone with whom I’ve argued or just can’t stand.

A candle is lit. A bell chimes. Benedictine bells, Joan Chittister writes, “call the attention of the world to the fragility of the axis on which it turns…Listen, The Rule of St. Benedict says. Listen, the bell says. Listen, monastic spirituality says.” The bells ask us to listen even when we’d prefer not to.

The sisters rise and bow to one another. It is a gesture that runs so counter to our American culture, where the handshake or the hug signals instant parity. By contrast, the monastic bow says “I humble myself before you.” How different that person across the aisle looks to me when I raise my head again, having acknowledged their presence, their worth, and my own limitedness. The sisters run a thumb across their lips, make the Sign of the Cross, and sing “Lord, open my lips and I shall proclaim your praise. I think of the day ahead. Can I make my actions a form of praise and not a cause for fear? Can I somehow make of this day one extended prayer?”

…

We will gather again three more times for prayer: at midday; at 5:30 for Evening Praise; and at twilight for Compline, the final prayers of the day. We will sing by candlelight the words that Simeon uttered when he realized he had finally seen the Savior: Nunc dimittis, servum tuum, Domine, secundum verbum tuum in pace.”Now Lord, let your servant go in peace, according to your promise.” The prayer permits me to put aside any misgivings I have about the day just past and any anxiety about the day to come. I am relieved of my duties; it is time to rest. Silence fills the monastery. Then we begin anew at dawn.