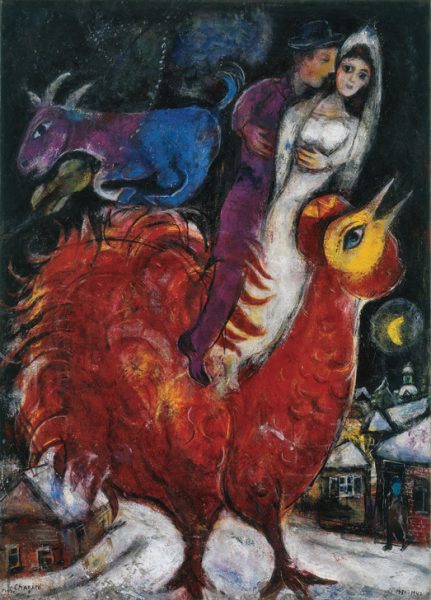

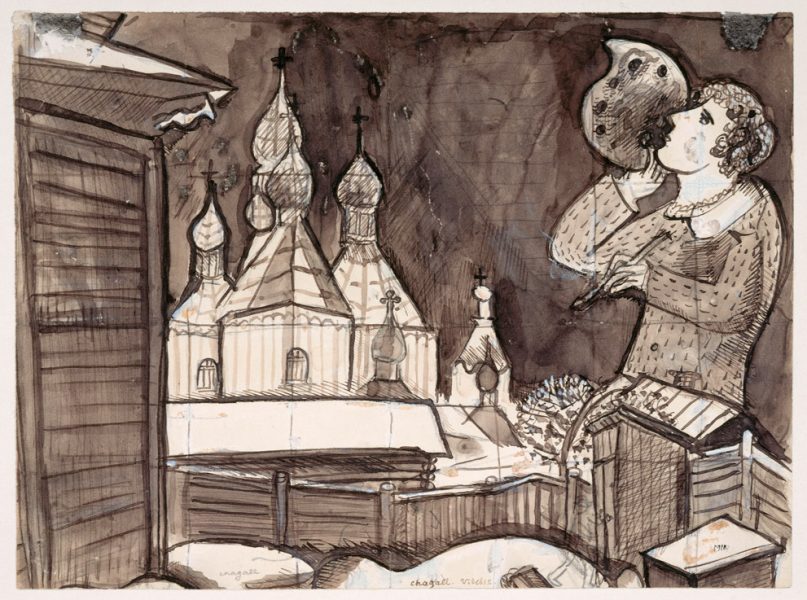

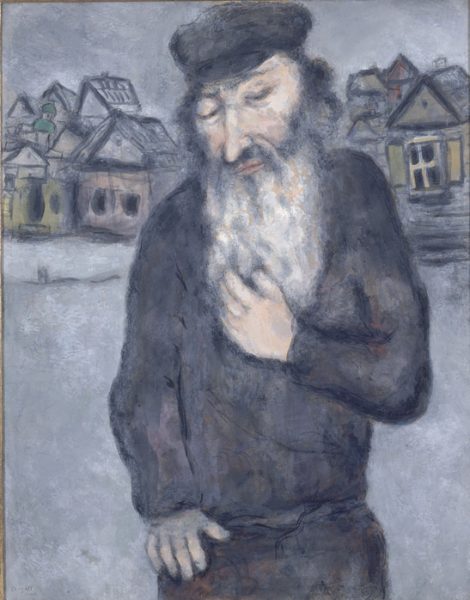

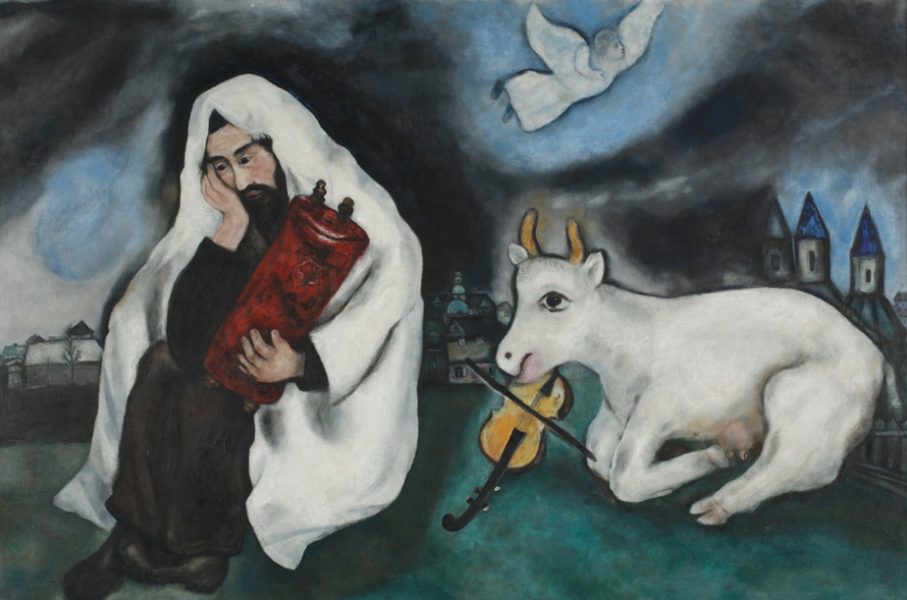

SUSAN GOODMAN (Senior Curator, Jewish Museum in NY): Chagall grew up in a shtetl in Vitebsk, in Belarus, and his family was Hassidic. Many of the images that we see throughout Chagall’s life derive from those early years. There’s the fish that keeps recurring that, perhaps, references the fact that his father was a laborer in a herring factory; the violin, which must relate back to the klezmer-players that he heard when he was a child, and, as he’s used it in many of the works, it seems to be a consoling instrument for these Jews that are in such dire straits. He personally experienced and knew about Jewish persecution and the pogroms that prevailed.

Solitude is an important work because it was created in direct response to Hitler’s election as chancellor in Germany. That was pretty early for him to do a painting with such despair, where we see the angel flying away as if abandoning the Jews to their fate.

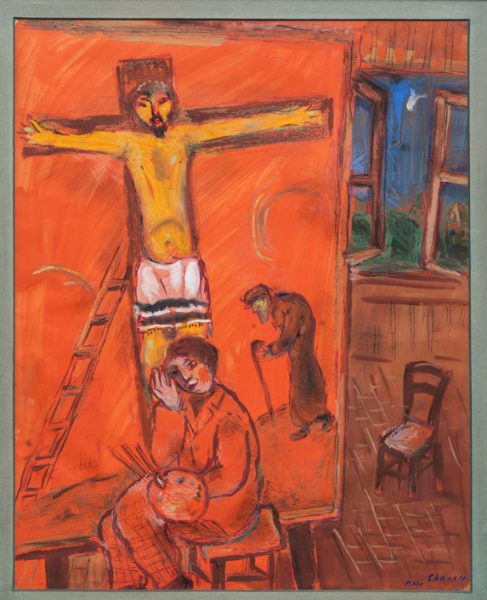

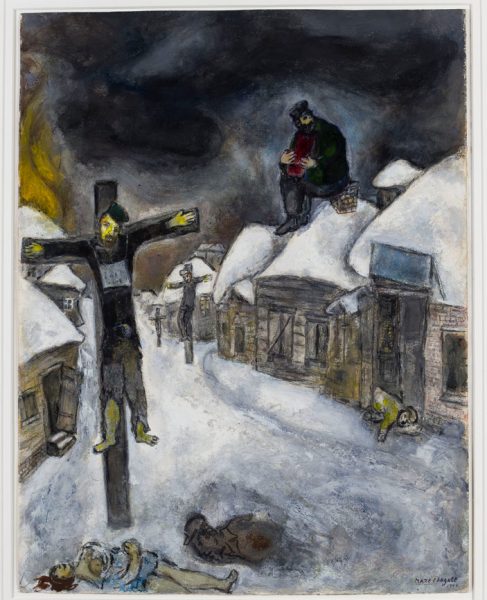

In 1938, Chagall starts to use the image of the Jewish Jesus. He could think of no more powerful way to convey his anguish at the annihilation of European Jewry. He equated the Jewish Jesus on a cross with the martyred Jewish people and he really did believe that if he could show the Christian community that the persecution of the Jews was essentially persecuting a Jew just like Jesus, who was one of “us” and one of “them.” There was an equivalence there.

That work that shows an explicit image of a Nazi comes from revelations in 1945 about the death camps, and Chagall was sitting in this country totally frustrated there was nothing he could do, and he felt the need to express it. It’s a very idiosyncratic work. And, in fact, the Jesus figure is nude, which is unusual for Chagall, and he’s wrapped in a tallit that covers his whole body.

He didn’t ever give up his connection to Judaism, he wasn’t an observant Jew, but as opposed to many of his co-religionists who actually did convert, Chagall never did. And, in fact he included and absorbed Jewish culture within his paintings, even the ones where he uses the Jewish Jesus.

In Exodus, it’s a complex theological painting, because there’s a Jesus figure, it’s definitely not Jewish, the figure is Jesus triumphant and it seems to me that the artist, Chagall, is identifying more with the Jesus figure than with Moses, who’s relegated to the right-hand corner.

The war was over. And the population needed a kind of spiritual uplift and hope, and to understand that the Jewish culture had survived. And he was able to provide this in a way that no other artist at the time could do. If we can contextualize the art that he created during these years and think about what he was going through, his experiences at the time, I think we will come up with a better understanding—a new understanding—of Chagall.