LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: London Tatum with her four-year-old daughter, Julianna, at a campus day care center: She’s finishing her bachelor’s degree at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, but she has concerns about the future.

LONDON TATUM: Education is really important, but it’s kind of like where do you go from here? I feel like it’s kind of like a prelude to hopelessness.

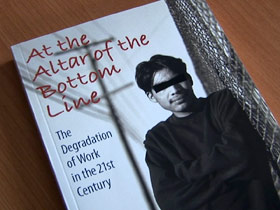

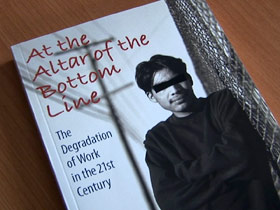

SEVERSON: Tom Juravich is a sociology professor at the University of Massachusetts, who has been writing about workers and the American workplace for over 25 years. His most recent book is about the struggling working class.

PROFESSOR TOM JURAVICH (Department of Sociology, University of Massachusetts at Amherst): We have this notion called the American Dream, and the dream has been for so many of us, was that life would be better for our children. And my dad was a factory worker, sent his three kids to state universities, and we all went forward never to look back.

SEVERSON: What do you think about the American Dream?

TATUM: It’s a nightmare. It doesn’t—I mean it’s an abstraction. It’s a dream, it’s a fantasy, it’s not realistic.

SEVERSON: It’s not realistic, she says, because jobs are so hard to find and good ones almost impossible.

TATUM: We watched our parents get successful jobs. We watched our parents be able to maintain a life in line with the house and the picket fence. Now it’s our time to do this, and it’s not materializing because the cost of things has risen, but wages have stayed the same, and full-time jobs have diminished.

JOHN CARR (Director, Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, Georgetown University): It’s stunning to see the charts, but it’s even more stunning to see the faces of people who have been left behind.

SEVERSON: John Carr has devoted his career to making the dream a reality for all Americans, including the poor. He is the director of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life at Georgetown University.

CARR: Who talks about the poor? Every year the Census Bureau comes out with the figures, and they’re sad figures; we’re doing worse, and the silence is deafening. The White House doesn’t talk about it; the Congress doesn’t talk about it.

SEVERSON: For over 20 years Carr was a principle advisor on social justice for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. He has worked, not always successfully, to encourage Washington policy makers to consider traditional Catholic social values in their decision-making.

CARR: Washington has become a place driven by money and power, and the poor don’t have money by definition, and they don’t have a lot of power. The idea that if you have to cut $40 billion from the agriculture budget you would cut all $40 billion from food stamps and nothing from affluent cotton farmers or rice farmers—couldn’t they go without, so mothers could feed their family? So it’s not a close call.

SEVERSON: What is not a close call is the growing income gap separating the wealthy from the rest. The disparity between the wealthiest one percent and the other 99 percent is wider in the U.S. than any other developed country. For instance, the richest 400 individuals own more wealth than the bottom 150 million. Economists say that’s one reason the American Dream is beyond the reach of so many Americans.

JURAVICH: So essentially although we’ve seen productivity rise dramatically over the last two decades, workers wages have been flat. If you look at that graph about when productivity and wages separated, what else happened at that time? Union membership plummeted. So unions were great equalizing institutions in this country. They helped to hold some constraints on the one percent and on corporations to level that playing field.

DR. SERENE JONES (President, Union Theological Seminary, New York City): It is a system dominated by a financial elite and their corporate connections that rules unquestioned.

SEVERSON: Serene Jones is the president of the nondenominational Union Theological Seminary. She is teaching a class this year about theology and economics.

JONES: One of my goals is to get pastors and congregations to feel emboldened to ask questions about the economy. Why is it that you have to pay more interest on a loan to go to college than banks have to pay for loans to support the banking industry? I mean, there’s some deep problems here.

JURAVICH: We have a generation that’s coming out now to a very precarious job market, who are saddled with some of the largest debt we see in this country. In fact, student debt, you know, is more that credit card debt in total.

JONES: The middle class in this country is no longer what we always think of when we think of the middle class as this sort of large, kind of healthy middle sector. The middle class and the poor are just inches away from each other.

CARR: We’re one nation, but we live in different economies. In one economy people are doing great. Then there’s the economy of people left behind. And then there’s this middle where a lot of us live, where we think we’re doing fine but we’re just scrambling to stay even. Two parents work hard, lots of hours, and yet you’re still one paycheck or one furlough or one illness away from trouble.

JURAVICH: The single largest job in the U.S. right now is retail sales, and the question is, how do you build a life and a family and a community around retail sales jobs?

SEVERSON: For his latest book, Juravich interviewed hundreds of workers and says our current society has two kinds of people—those who are not working, and those working too much.

JURAVICH: We have 400,000 nurses in the U.S. who have voluntarily left the profession. Why? Because of the working conditions. Here we have a nursing shortage, but the shortage isn’t because we don’t have enough people coming in. It’s that people are leaving because so many health-care facilities require so much, a massive amount of overtime.

TATUM: The corporations—they have the voice, and they say what goes.

SEVERSON: And you don’t have a voice?

TATUM: I have a voice, but it’s marginalized. I have a voice, because I believe in creating a better future. I have a voice, because I’m an idealist. But imagine how many other people don’t feel like they can affect change.

CARR: There’s a passion deficit. There’s a priorities problem. The Scriptures put the poor first. Washington does not. And I think one of the challenges of the religious community is to match the urgency of the situation with the urgency of their advocacy.

SEVERSON: But at Union Theological Seminary, Serene Jones sees no “passion deficit” among her students.

JONES: You read Dr. King’s work about the sort of deep connection to the soul out of which activism comes. I see that in my students, and I haven’t seen that in the last 20 years like I have in the last two or three years.

SEVERSON: At the University of Massachusetts, Tom Juravich also sees signs that change might be coming from the bottom up.

JURAVICH: We saw this in the Occupy movement—that people are beginning to be angry, and they are beginning to organize, and I think that there’s a lot of nascent activity happening within social movements in this country that could be the basis of something different.

CARR: The fundamental question is, who are we as a nation? And very few people are asking that. The churches, the synagogues, the mosque I think are struggling to do that, but they do it in a very hostile political culture.

SEVERSON: London Tatum thinks the government needs look out more for the people.

TATUM: And as citizens we are the people, so therefore the government is for us, but it doesn’t work that way. The government is, you know, for Goldman Sachs, it’s for JP Morgan, you know, it’s for Halliburton, you know, it’s for them. It should be for us, though.

SEVERSON: Next year, London plans to work on a master’s degree in labor studies. She gets part-time work, but she’ll need to go deeper in debt to get the advanced degree she thinks she needs to get a “meaningful” job.