FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: One solitary cross is all that suggests that this is a cemetery, and perhaps that's fitting. The several hundred people buried here spent most of their lives invisible to the outside world. There are no headstones in this burial ground of a former Minnesota mental institution. The graves are marked not with names, just numbers. The relatives of Albertine Poitras had to go through historical archives to find her number.

Relative: “That’s Albertine.”

DE SAM LAZARO: A few years ago, a disability rights group began working to change this. Their project is called Remembering with Dignity.

Leader: We are here today to remember and honor Albertine Poitras.

DE SAM LAZARO: Recently, on a chilly Minnesota fall morning, they gathered at the cemetery to honor the long departed great-aunt of Blair Poitras. He only learned that she existed a few years ago while doing a genealogy search. Then he confirmed it with his 89-year-old aunt, who is Albertine's niece.

BLAIR POITRAS: You go through different emotions. You go, well, how come your family members didn’t tell you about this person? And just to be buried as a number...

OLIVE POITRAS KEELY: I remember her. She lived with us out on the farm.

DE SAM LAZARO: That memory is all this family has. There are no photographs of Albertine Poitras, born in 1898 with mental retardation. In 1932, as families struggled to survive the Depression, Albertine became a burden neither her aging parents nor her siblings could endure.

OLIVE POITRAS KEELY: We had hired men, too, and my mother always thought the hired men would take advantage of my aunt because she was feeble-minded.

DE SAM LAZARO: At 34, Albertine Poitras was committed to the school for the feeble-minded in Faribault, Minnesota. She became a ward of the state. The name of the Faribault facility has changed over the years, reflecting society’s evolving views of people with mental illness and retardation. In the late 1800s, this officially was the school for deaf, dumb, blind, idiots and imbeciles. “Feeble-minded” came into use in the early 1900s, and by the fifties this was simply Faribault State Hospital. Today it’s a minimum security prison. Faribault was considered an innovation when it was founded, an attempt to educate the mentally disabled. But in time, Remembering with Dignity's Mary Kay Kennedy says that early mission was forgotten.

MARY KAY KENNEDY: The peak of the population at this site was in the 1950s, and it housed 3,355 people, which was about 45 percent over capacity, so there was no education, so it really turned into a facility that was taking care of the basic physical needs of the people who lived here.

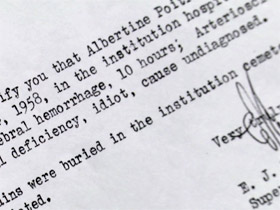

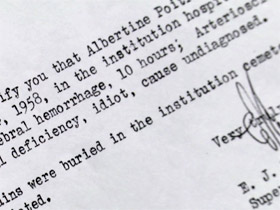

DE SAM LAZARO: For people who died here, funerals were basic, businesslike affairs. Blair Poitras says notice of Albertine's death was sent not to the family first, but to the welfare department supervisor.

BLAIR POITRAS: (reading letter) Dear Mr. Kaliher: This is to notify you that Albertine Poitras died at 8:25 p.m. on February 4, 1958 in the institutional hospital. Cause of death was cerebral hemorrhage 10 hours, arteriosclerosis 20 years, mentally deficient, idiot. Cause: undiagnosed.

LARRY LUBBERS: They didn’t treat us people very nice. They didn't treat us people with no kindness, no respect, or nothing in those days.

DE SAM LAZARO: At the cemetery, former residents reflected on their time in Faribault. Larry Lubbers spent ten years here. He was moved to a group home as mental health care shifted away from large institutions. Dorothy Anderson was committed as an infant.

DOROTHY ANDERSON: I didn’t know my mother or if she was married, or my grandma. And I didn’t have no pictures to remember them by.

DE SAM LAZARO: This group successfully lobbied Minnesota's legislature, which in 2010 officially apologized for the past treatment of state hospital patients.

MARY KAY KENNEDY: The apology extends to family. Professionals advised people to break ties with the family, and there were no other services, so if you had a child or someone with a severe disability it wasn’t like today, where you could get services in the community.

DE SAM LAZARO: Others have a more nuanced view of how the treatment of mentally disabled people has shifted over the years. Jean Hockman's sister, Barbara Blaylock, died here in 1958 at the age of five.

JEAN HOCKMAN: I think when you look at the state of Minnesota and some of the needs of the homeless who are mentally ill, institutions might be a good thing for them. I don’t think everybody belongs in an institution. I think there’s a happy medium, and I don’t think society has found it yet.

DE SAM LAZARO: There's very little disagreement about adding names and gravestones to the numbers here.

HALLE O'FALVEY: The Jewish saying is that you die twice. You die once when you do die, but the second time you die is when your name isn’t spoken anymore.

DE SAM LAZARO: So far the group has installed almost 7,000 personalized gravestones on the 13,000 numbered graves they've discovered across the state until now, with funding from Minnesota's legislature.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Faribault, Minnesota.