In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

1963: Civil Rights 50th Anniversary

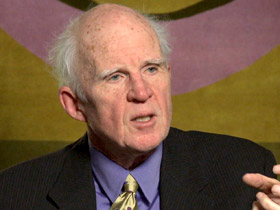

The civil rights movement was both “the work of the Lord and the work of freedom,” says author Taylor Branch. “It took redemption, and it took faith and tenacity, not just an empty, simple hope.”

Read an excerpt from The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Right Movement (Simon & Schuster, 2013) by Taylor Branch:

“The Time Has Come for This Nation to Fulfill Its Promises”

[On Tuesday, June 11, 1963], as President Kennedy and the Attorney General anxiously awaited the outcome of the school segregation showdown with Alabama Governor [George] Wallace, a telegram came in from Martin Luther King on the “beastly conduct of law enforcement officers at Danville.” Asserting once again that “the Negro’s endurance may be at the breaking point,” King implored the Administration to seek a “just and moral” solution…There was a rougher, public message from King on the front page of The New York Times…[which] quoted his plea that, above all, President Kennedy must begin speaking of race as a moral issue, in term “we seldom if ever hear” from the White House.

[On Tuesday, June 11, 1963], as President Kennedy and the Attorney General anxiously awaited the outcome of the school segregation showdown with Alabama Governor [George] Wallace, a telegram came in from Martin Luther King on the “beastly conduct of law enforcement officers at Danville.” Asserting once again that “the Negro’s endurance may be at the breaking point,” King implored the Administration to seek a “just and moral” solution…There was a rougher, public message from King on the front page of The New York Times…[which] quoted his plea that, above all, President Kennedy must begin speaking of race as a moral issue, in term “we seldom if ever hear” from the White House.

Given his recent sensitivity to King’s opinions, these urgings may have influenced President Kennedy’s extraordinary decision to make what amounted to an extemporaneous civil rights address on national television. The causes were uncertain because the notion of a speech came so suddenly from the President himself, without a trace of the usual gestation within the government. When he startled his advisers on Tuesday with the thought that he might announce his civil rights legislation on television that night, no one liked the idea…There was no speech draft. There had been no consultations with Congress or anyone else on what the President planned to say. To make a naked dash that very night on so sensitive an issue seemed like the worst sort of presidential whim, but Kennedy refused to let it go….Toward six o’clock that evening, President Kennedy ordered fifteen minutes of network time at eight. He gave speechwriter Ted Sorensen some general ideas and some scraps he like from Negro aide Louis Martin, then sent him off to write a speech within two hours.

Minutes before eight, Sorensen came into the Cabinet Room with a draft that President Kennedy found workable but stiff. He began tinkering to add paragraphs of fervor and rhetoric, dictating to Evelyn Lincoln while Sorensen cross-dictated to Gloria Liftman. They retyped pages and fragments, inserting them here or there in the stack as opinions changed in the mad fit of purpose. [Burke Marshall] was aghast with the realization that there would be no finished text—that the leader of the free world was about to ad-lib on national television—but as the seconds ticked away the President was at his best, wired both hot and cool. “Come on now, Burke,” he prompted. “You must have some ideas.”

The President’s first peroration before the cameras was a bit awkward, on the refrain “it ought to be possible,” but then he broke through with a sketch from Louis Martin contrasting the life chances of two newborn American babies, one white and one Negro. “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue,” he declared. “It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated.”

These words brushed along a religious course that was starkly out of character for the worldly President. Their flow transformed even his approach to the global struggle:

We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it. And we cherish our freedom here at home. But are we to say to the world—and much more importantly, to each other—that this is the land of the free, except for Negroes, that we have no second-class citizens, except Negroes, that we have no class or caste system, no ghettos, no master race, except with respect to Negroes?

Now the time has come for this nation to fulfill its promise. The events in Birmingham and elsewhere have so increased the cries for equality that no city or state or legislative body can prudently choose to ignore them…We face, therefore, a moral crisis as a country and a people…A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all.

Kennedy wandered on and off his text, outlining his forthcoming legislation. He kept inserting parenthetical phrases signaling that race was no longer an issue of external charity or deflection: “We owe them, and we owe ourselves, a better country.” When he ran out of text, he coasted unevenly to the end. By then, it didn’t matter.

In Atlanta, King drafted an instant response, with errors characteristic of his own uncertain typing and spelling. “I have just listened to your speech to the nation,” he wrote. “It was one of the most eloquent[,] profound and unequiv[oc]al pleas for Justice and the Freedom of all men ever made by any President. You spoke passionately to the moral issues involved in the integration struggle.” An equally excited Stanley Levison [King’s closest white friend and adviser] called King that night to say that President Kennedy had done “what you have been asking him to do.” To Levison, the historic speech underscored the importance of their decision to make Congress, not President Kennedy, the focus of the Washington demonstration.

In Jackson, [Mississippi], all three [Medgar] Evers children, including toddler Van Dyke, tumbled in their parents’ bed, arguing over which television program to watch. Their mother had allowed them to stay up past midnight to find out what their father thought of the President’s wonderful speech, and they all rushed for the door when they hear his car. Medgar Evers was returning from a glum strategy session. All but nine of the seven hundred Jackson demonstrators were out of jail. Local white officials were claiming victory untainted by concession. Both the white and Negro press portrayed the Jackson movement as shrunken, listless, riddled by dissension. Privately, Evers had asked for permission to invite Martin Luther King to join forces, but his NAACP bosses ignored the heretical idea. Finally home, Evers stepped out of his Oldsmobile carrying a stack of NAACP sweatshirts stenciled “Jim Crow Must Go,” which had made poor sales items in Mississippi’s sweltering June. His own white dress shirt made a perfect target for the killer waiting in a fragrant stand of honeysuckle across the street. One loud crack sent a bullet from a .30-’06 deer rifle exploding through his back, out the front of his chest, and on through his living room window to spend itself against the kitchen refrigerator. True to their rigorous training in civil rights preparedness, the four people inside dived to the floor like soldiers in a foxhole, but when no more shots came, they all ran outside to find him lying face-down near the door. “Please Daddy, please get up!” cried the children, and then everything fell away to blood-smeared, primal hysteria. The victim said nothing until neighbors and police hoisted the mess of him onto a mattress and into a station wagon. “Sit me up!” he ordered sharply, then “Turn me loose!” These were the last words of Medgar Evers, who was pronounced dead an hour later.

The Evers murder came at the midpoint of a ten-week period after the Birmingham settlement when statisticians counted 758 racial demonstrations and 14,733 arrests in 186 American cities. Two men demanding integration chained themselves to the gallery of the Ohio legislature. An Alabama mob stoned the home of a white preacher who suggested that Negroes be allowed to worship in his church….Like Kennedy’s speech, the murder of Medgar Evers changed the language of race in American mass culture overnight. The killing was called an assassination rather than a lynching, Evers a martyr rather than a random victim—recognized as such with a post-funeral cortege by train to Washington and a family audience of condolence at the White House.

From The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Right Movement (Simon & Schuster, 2013) by Taylor Branch