MONA HANFORD: The reason I like staying in this house—it’s a symbol. I sort of feel Bill around me.

ROBERT FAW, correspondent: Mona Hanford lost her husband Bill little more than a year ago. Now the massive Camellia tree in her backyard gives her comfort.

MONA HANFORD: The camellia’s special because when Bill died last year, he was in his hospital bed, in the family room, looking out on the garden and the camellia. And it bloomed just as he died. So on the anniversary of his death, it came back. It’s sort of like bookends to my year.

FAW: It has been over four years since Dolores Royston lost her husband, Paul. She will never forget her intense loneliness after he died.

DOLORES ROYSTON: I think the loneliness is something that nobody can really prepare you for. That loneliness, the emptiness, is more than you can describe. Because he was so close to me and he’s my best friend, and that’s what you miss.

FAW: On Good Friday, Mariann Budde, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, D.C., delivered a sermon about loss and grieving.

BISHOP MARIANN BUDDE (Episcopal Church): How do we bear it? How do we bear the sadness? I think naming it and acknowledging it for what it is. To have people that you can talk to, or places you can go, or rituals that can help hold or contain the emotion. We endure these losses time and again and are able to become large enough to hold it and continue on with our lives.

FAW: George Bonanno, psychologist and author of the book "The Other Side of Sadness," says research shows while ten to fifteen percent of mourners do suffer depression and might need medical intervention, for the rest, though their loss is always with them, the pain subsides and they can cope because that’s how humans have evolved.

GEORGE BONANNO (Author, "The Other Side of Sadness"): Basically having an acute sadness reaction that comes and goes, but continuing to function, being able to talk to other people and care for other people and concentrate and do whatever job you need to do. I think this comes from our biological wiring. These biological and adaptive systems are extremely effective and they allow us to cope with things. We’ve been doing it since the beginning of time.

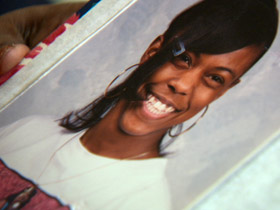

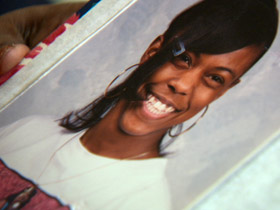

FAW: Coping though was something Daniel Perez could not manage when his daughter Emily, a West Point graduate, was killed while serving in Iraq.

DANIEL PEREZ: I opened the door, and there was two people in uniform standing there. I just closed the door and said y’all got the wrong house.

FAW: After the initial shock, Perez says he was so consumed tending to his daughter’s burial and personal effects and taking care of his wife Vicki, he could not really take time to mourn. Until one day...

DANIEL PEREZ: I went out to the mailbox and there was a big brown envelope and it was actually addressed to me. And when I opened it, it was 20 or 30 letters that were written by an elementary class, addressed to the father. So then, that’s kind of when everything kind of flooded out then. Yeah.

FAW: For Vicki, grief–immediate and overwhelming–soon undermined her once deep faith.

VICKI PEREZ: I had a fight with God. I’m like, you know, I did what you told me to. The child had incredible faith, and she honored us just by the things she did—HIV/AIDS Ministry started at the church, in the choir, tutoring. She brought honor to her mother and her father, she brought honor to the whole family. And yet, you decide that, you allowed this to happen, not decided, you allowed this to happen, and so my faith was shook.

FAW: Vicki’s response is not unusual, says Kenneth Pargament, a clinical psychologist at Bowling Green University who has studied grieving and religion.

KENNETH PARGAMENT (Bowling Green University): A trauma can call into question one's entire assumptions about life, whether life is good, whether there is a god who cares, whether there’s reasons to be hopeful about ourselves, whether our lives have any meaning at all.

FAW: For Dolores, a strong faith never wavered. Indeed, she says, it grew stronger as did her belief in an afterlife.

DOLORES ROYSTON: I believe firmly in an afterlife. I can’t imagine living on this earth, going through what you go through, especially with my husband’s illness, and not have a better reward somewhere.

FAW: Likewise for Cynthia Woods, still saddened by her mother’s death 8 months ago but now also at peace.

CYNTHIA WOODS: When I saw her after she had passed, there was a glow on her face. She was looking up and off as if she was seeing Jesus and being received. And that just solidified my faith in what we believe in, that our life in Christ here is not in vain. And that we will see her again. But she is at her reward.

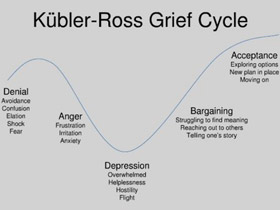

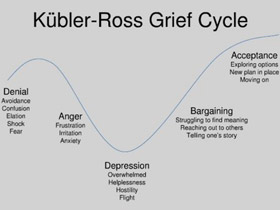

FAW: Experts agree there is no one way–no right or wrong way–to grieve. And the notion that there’s a set of stages of grief—denial, anger, depression, bargaining and acceptance, stages popularized by Elizabeth Kubler Ross–has been challenged, even discredited.

BONANNO: Lots of people have contacted us in the past to point out that it’s really been harmful to them because they didn’t go through anything remotely like that and there was an expectation that they should or there must be something wrong because they’re not. They’ve contacted me to say, “Thank you for saying that because I’ve been fine and everybody keeps telling me there’s something wrong.”

FAW: Of course for many people, religious traditions, especially rituals, help make grieving endurable.

PARGAMENT: In these times then, we need the rituals to help us negotiate this bridge between normal person and mourner, between living and death. So we need rituals to help us facilitate the transition and yet sustain ourselves at the same time. Religious rituals serve the purpose of both continuity and change.

FAW: For Mona Hanford, butterflies, representing hope, became a spiritual symbol.

HANFORD: We had these butterflies on the altar. We had hundreds of them.

FAW: And some people, like Jeanne and Livia Kent, create their own symbols. When Charles—Jeanne’s husband and Livia’s father—died a little more than a year ago, they devised a memorial service three months later to celebrate his life.

JEANNE KENT: Preparing for the service was wonderful and it was a comfort and it was being creative and it was accessing my creative energies that helped release my sorrow.

LIVIA KENT: Nothing was imposed upon us. We had this wonderful freedom to just pull from our hearts and what was meaningful for us, and create a splendid celebration for this man. There were many rituals that we just made up.

DANIEL PEREZ: (reading letter) Dear Daniel and Vicki, with the deepest sympathy, you are in my prayers wishing you peace at this time of sorrow.

FAW: These days Daniel Perez copes with his grief by turning to an imaginary box.

DANIEL PEREZ: Every now and then I pull the box out. I’ll have my moment, I’ll shed some tears, and then I close the box back up. So it’s something that will never go away, I just had to learn how to manage it so that it wouldn’t overtake me.

FAW: However mourning is expressed, the process almost invariably changes attitudes, even lives.

BUDDE: Time and again you’ll hear people say, "You know, after this happened, I made a course correction because I realized that life is precious and I’m not going to spend my time on things that this little time that I have left, I’m not going to spend it on the things that are not of ultimate importance to me."

ROYSTON: Stripping yourself of all the things that aren’t important anymore. It just tells me that there is a God and he’s close to me and he’s helping me.

JEANNE KENT: I’m a different person and stronger person and a more compassionate person. I think a more knowing person deep down.

FAW: For Daniel Perez, faith–once shaken–was eventually restored.

DANIEL PEREZ: You wind up accepting what happened knowing that you had no control over it and you never understand why God does what he does. So you wind up I guess accepting that okay, this happened, now what can we do about that?

FAW: Setting up a foundation, established in Emily’s name to help young women, has helped Daniel and his wife to manage their grief and start living again.

VICKI PEREZ: I have joy, I got my joy back. It’s just a good feeling that she lives on through us. Emily forces us to reach out and help others and this is what she would have us to do, so therefore, we do it.

FAW: So the loss of a loved one can be the closing of one door and the opening of another.

BUDDE: We become less human, I think, if we don’t tend to grief in an open-hearted and generous way. We pick up and face into that abyss and say yet I will live. Yet I will pass on life and joy, even if I can’t know it myself, I will ensure that others will, and I will find my greater meaning in that.

FAW: For Religion and Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Bob Faw in Washington, D.C.