David DeCosse: Edward Snowden and the Moral Worth of Civil Disobedience

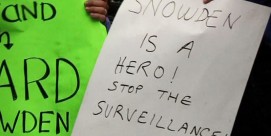

Edward Snowden, the former National Security Agency employee responsible for one of the largest leaks in American history, has been viewed through many lenses: patriot, whistleblower, traitor, spy.

But what about seeing his actions in light of the tradition of civil disobedience? This was the focus of a recent event called “Conscience, Edward Snowden, and the Internet: Has Civil Disobedience Gone Too Far?” hosted by the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University in Santa Clara, California.

The framework of civil disobedience allows more latitude for actions we would otherwise condemn outright. Great historical figures like Martin Luther King Jr have emblazoned civil disobedience on contemporary consciousness.

So where does Snowden stand in this tradition? The consensus at the Santa Clara University event was that Snowden could indeed be placed within such a framework. In other words, he wasn’t simply a reckless outlaw (much less a traitor or spy).

But within that consensus were two sharply different views of the moral worth of his civil disobedience. One view held that his actions were justifiable across the board as a corrective to the systemic overreach of the National Security Agency. (My colleague on the panel with me at the event, Irina Raicu, director of Internet ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, held such a view.) The other view acknowledged a far more limited justification for his actions on account of his Internet culture-inspired libertarian philosophy.

Snowden’s actions have been most justifiable when he has closely linked the existence of once secret NSA programs to broadly acknowledged values that a particular program may have violated. The best example here was his revelation of the existence of NSA troves of metadata on the phone calls of Americans—a revelation that rightly raised general concerns about the protection of privacy. But he has also, in the name of transparency, revealed things of far more ambiguous value (for instance, NSA spying on the political leaders of American allies) and stolen such a massive numbers of files that it’s not clear what more specific values are at stake in such a huge theft.

Snowden’s actions are best explained by situating him within the libertarian tradition of “information freedom” represented by figures like Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning. For these figures, information freedom largely means the “freeing of information” from its secret hold by massive institutions.

It is important here to note that the ethical issue isn’t so much what the information is about; the issue is that the information is being kept secret at all (as if secrecy is inherently evil) and ought to be freed, especially so people can make decisions. This is a new, Internet version of old-time libertarianism. The assumption is that the privacy of the isolated individual is pitted against the information-amassing, secrecy-obsessed, power-mad state or corporation.

But this makes things too simple, especially for what we expect in acts of civil disobedience. Two key differences between Snowden and Martin Luther King Jr’s example make this clear. The first pertains to what King called “negotiation,” the second of four key steps leading toward direct, nonviolent civil disobedience (the others are study, self-purification, and the direct action itself).

For King, the duty to negotiate revealed, among other things, a good-faith belief that even the segregationists running the government in cities like Birmingham, Alabama, were fellow human beings with a capacity to learn and be just. If Martin Luther King Jr could seek to negotiate with Bull Connor, Birmingham’s police chief, why couldn’t Edward Snowden transcend the libertarian cynicism toward government officials and try to speak with known NSA critics like Senators Ron Wyden and Rand Paul?

The second key difference pertains to King’s conviction that all those engaging in civil disobedience must be willing to accept legal punishment for their actions. At bottom, this concern was a way to reaffirm the value of the law in itself. Moreover, submitting to such punishment was also a way to affirm by word and deed the moral good of the political community. By contrast, of course, Snowden now sits in Russia, avoiding such accountability and thus also undermining the value of both the law and the political community. Trapped in libertarian polarities, he remains the lonely, heroic individual squaring off against the vast power of the state.

But he would be truer to what is morally at stake in his actions and to the highest tradition of civil disobedience if he came home to face the consequences.

David DeCosse is director of campus ethics programs at Santa Clara University’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics.