Read an excerpt from People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: At the Arsenal Center for the Arts in Boston, a multimedia performance called “Music of the Book” is telling the story of the Sarajevo Haggadah and its journey of survival from fourteenth-century Spain, the expulsion of the Jews, and the Inquisition through the Nazi Holocaust and the Bosnian war. Sarajevo-born composer Merima Kljuco says the haggadah’s story touches Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike.

MERIMA KLJUCO (Composer, Music of the Book): It went through so many different cultures, and so many different people took the care of the book and helped it survive.

LAWTON: The Sarajevo Haggadah was created in the mid-1300s in Spain, during a period when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived together in relative harmony. Religion professor Marc Michael Epstein has a rare facsimile of the haggadah.

LAWTON: The Sarajevo Haggadah was created in the mid-1300s in Spain, during a period when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived together in relative harmony. Religion professor Marc Michael Epstein has a rare facsimile of the haggadah.

MARC MICHAEL EPSTEIN (Professor, Vassar College/Boston College): It is highly probable that many Jews owned beautifully illuminated manuscripts, but we are left with only a very small percentage of what was actually made.

LAWTON: The manuscript’s rich illuminations are similar to those in medieval Christian books.

EPSTEIN: You see how the divine is indicated here with gold flames or rays.

LAWTON: In addition to scenes from the Book of Exodus, the illuminations also depict scenes from Genesis. There’s the creation story, ending with a Jewish man resting on the Sabbath. There’s Adam and Eve, Jacob’s dream of a ladder to Heaven, and, of course, the Exodus out of Egypt and the Passover celebration that commemorates it.

EPSTEIN: Here the bitter herb is illustrated as romaine lettuce, as a head of romaine lettuce. Romaine lettuce was preferred because when you start chewing on a piece of romaine lettuce it tastes like salad, you know, you feel like, oh, I’m eating a salad. But if you keep chewing on it, it becomes more and more bitter, and that is the experience of slavery.

LAWTON: Epstein says the family that commissioned it likely had themselves put into the book.

LAWTON: Epstein says the family that commissioned it likely had themselves put into the book.

EPSTEIN: This is very important because the tradition of Jews on Passover is that one should see oneself as if one had personally come out of Egypt. And by putting oneself visually into the art, one has an opportunity to do this.

LAWTON: Included at the Seder table is an intriguing figure, a woman with dark skin. Some believe she was a servant, although she is seated with the family. The illustrations paint a vivid picture of medieval Jewish life. Doodles and red wine stains on the pages show the haggadah was well-used at Passover celebrations.

EPSTEIN: The haggadah, then as now, was used in a kinetic environment. It was used at a Seder table with grandparents and grandchildren and children screaming and people saying, “When are we going to eat,” right? This is the history of all haggadot, the Sarajevo Haggadah not the least among them.

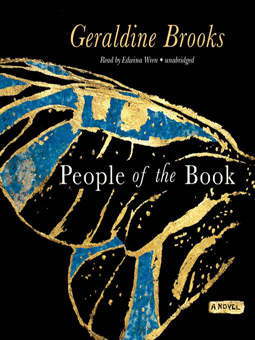

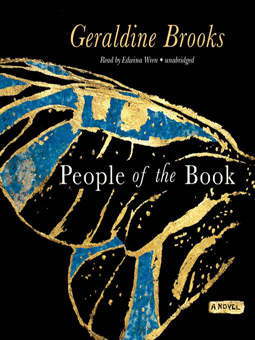

LAWTON: The Sarajevo Haggadah has captured the imagination of millions, including Pulitzer Prize-winning author Geraldine Brooks.

GERALDINE BROOKS (Author, People of the Book): It is a magnificent work of art, and we know nothing about the artist, the painter who created those beautiful illuminations.

LAWTON: Brooks wrote People of the Book, a fictional story expanding on real events surrounding the haggadah, going back to when it was created.

LAWTON: Brooks wrote People of the Book, a fictional story expanding on real events surrounding the haggadah, going back to when it was created.

BROOKS: This was a really thriving, affluent, comfortable community. And you get that real sense of a community, part of a bigger community in the illustrations, the security of their life. You realize what a shock it must have been for them to find that this really was so fragile.

LAWTON: In 1492, Jews were expelled from Spain and were able to take out only a few books like the haggadah.

EPSTEIN: Because they were small and portable, people took them with them and concealed them and were able to take them out as the great treasures of their family, which of course have become the great treasures of the Jewish people and of the world.

LAWTON: A notation in the book places it in Italy in 1609, where it was examined, and approved, by a Catholic Inquisitor.

EPSTEIN: This is the signature of the Inquisitor who looked over the book and found nothing theologically objectionable in the text, let’s say. We’re not sure if he examined the illustrations.

LAWTON: In 1894, records show that a man named Joseph Kohen sold the haggadah to the National Museum in Sarajevo. During World War II, the Nazis tried to take it from the museum, but a Muslim librarian hid it from them. His widow told Geraldine Brooks it was kept safe in a mosque. The book was back in the museum by 1992, when the city came under heavy shelling during the Bosnian war. Another Muslim librarian risked his life to retrieve the manuscript and put it in a bank vault.

KLJUCO: Coming from Bosnia, Sarajevo Haggadah is kind of a symbol of co-existence, a symbol of caring for the culture that is also your culture, but also culture of your neighbors.

KLJUCO: Coming from Bosnia, Sarajevo Haggadah is kind of a symbol of co-existence, a symbol of caring for the culture that is also your culture, but also culture of your neighbors.

LAWTON: Merima Kljuco read Brooks’s book and was inspired by how the haggadah’s story reflected her own experiences in the Bosnian war, something she tried to convey through her music.

KLJUCO: I had my own exodus about 20 years ago, when Bosnia was attacked. And I was in the war for two years, so I also know what does it mean to feel the violence, and what does it mean to hide and to leave your own country, and to go somewhere else and build your own life again.

LAWTON: Aleksandra Buncic was also born in Sarajevo and displaced during the war. She is now a Fulbright fellow at Rutgers University, doing her thesis on the Sarajevo Haggadah. Buncic is one of the few historians who has been allowed to touch and study the actual manuscript.

ALEKSANDRA BUNCIC (Historian): I do remember how one of the curators carefully opened the door and took it as he's carrying child, and he put it and presented to me. That is a very emotional moment in my private and my professional history.

LAWTON: The haggadah is kept in a special case inside the National Museum in Sarajevo, but the museum has been closed since late 2012.

BUNCIC: Unfortunately, after 125 years, the museum is now closed due to political reasons, and there is no proper funding, which is the major problem and one of the reasons why the museum is closed today.

LAWTON: Despite its uncertain future, Brooks says the Sarajevo Haggadah’s story is one of ultimate hope.

BROOKS: Even though we succumb so easily to this demonization of the other, what's happened every single time is that there is always a few people who are able to stand apart and say, “No, not this way. What unites us is greater than what divides us.” And that gives me hope for us as a species.

LAWTON: For Jews and so many others, the Haggadah’s journey from times of persecution to survival and hope is a poignant echo of the Exodus story in the manuscript’s illuminated pages.

I’m Kim Lawton in Boston.

EXCERPT: PEOPLE OF THE BOOK

Read an excerpt from People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks

A book is more than the sum of its materials. It is an artifact of the human mind and hand. The gold beaters, the stone grinders, the scribes, the binders, those are the people I feel most comfortable with. Sometimes, in the quiet, these people speak to me. They met me see what their intentions were, and it helps me do my work. I worried that the kustos, with his well-meaning scrutiny, or the cops, with the low chatter of their radios, would keep my friendly ghosts at bay. And I needed their help. There were so many questions.

A book is more than the sum of its materials. It is an artifact of the human mind and hand. The gold beaters, the stone grinders, the scribes, the binders, those are the people I feel most comfortable with. Sometimes, in the quiet, these people speak to me. They met me see what their intentions were, and it helps me do my work. I worried that the kustos, with his well-meaning scrutiny, or the cops, with the low chatter of their radios, would keep my friendly ghosts at bay. And I needed their help. There were so many questions.

For a start, most books like this, rich in such expensive pigments, mad been made for palaces or cathedrals. But a haggadah is used only at home. The word is from the Hebrew root ngd, “to tell,” and it comes from the biblical command that instructs parents to tell their children the story of the Exodus. This “telling” varies widely, and over the centuries each Jewish community has developed its own variations on this home-based celebration.

But no one knew why this haggadah was illustrated with numerous miniature paintings, at a time when most Jews considered figurative art a violation of the commandments. It was unlikely that a Jew would have been in a position to learn the skilled painting techniques evinced here. The style was not unlike the work of Christian illuminators. And yet, most of the miniatures illustrated biblical scenes as interpreted in the Midrash, or Jewish biblical exegesis.

I turned the parchment and suddenly found myself gazing at the illustration that had provoked more scholarly speculation than all the others. It was a domestic scene. A family of Jews—Spanish, by their dress—sit at a Passover meal. We see the ritual foods, the matzoh to commemorate the unleavened bread that the Hebrews baked in haste on the night before they fled Egypt, a shank bone to remember the lamb’s blood on the doorposts that had caused the angel of death to “pass over” Jewish homes. The father, reclining as per custom, to show that he is a free man and not a slave, sips wine from a golden goblet as his small son, beside him, raises a cup. The mother sits serenely in the fine gown and jeweled headdress of the day. Probably the scene is a portrait of the family who commissioned this particular haggadah. But there is another woman at the table, ebony-skinned and saffron-robed, holding a piece of matzoh. Too finely dressed to be a servant, and fully participating in the Jewish rite, the identity of that African woman in saffron has perplexed the book’s scholars for a century.

Slowly, deliberately, I examined and made notes on the condition of each page. Each time I turned a parchment, I checked and adjusted the position of the supporting forms. Never stress the book—the conservators chief commandment. But the people who had owned this book had known unbearable stress: pogrom, Inquisition, exile, genocide, war.

As I reached the end of the Hebrew text, I came to a line of script in another language, another hand. Revisto per mi. Gio. Domenico Vistorini, 1609. The Latin, written in the Venetian style, translated as “Surveyed by me.” Were it not for those three words, placed there by an official censor of the pope’s Inquisition, this book might have been destroyed that year in Venice, and would never have crossed the Adriatic to the Balkans.

“Why did you save it, Giovanni?”

From People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks (Penguin Books, 2008)

LAWTON: The Sarajevo Haggadah was created in the mid-1300s in Spain, during a period when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived together in relative harmony. Religion professor Marc Michael Epstein has a rare facsimile of the haggadah.

LAWTON: The Sarajevo Haggadah was created in the mid-1300s in Spain, during a period when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived together in relative harmony. Religion professor Marc Michael Epstein has a rare facsimile of the haggadah. LAWTON: Epstein says the family that commissioned it likely had themselves put into the book.

LAWTON: Epstein says the family that commissioned it likely had themselves put into the book. LAWTON: Brooks wrote People of the Book, a fictional story expanding on real events surrounding the haggadah, going back to when it was created.

LAWTON: Brooks wrote People of the Book, a fictional story expanding on real events surrounding the haggadah, going back to when it was created. KLJUCO: Coming from Bosnia, Sarajevo Haggadah is kind of a symbol of co-existence, a symbol of caring for the culture that is also your culture, but also culture of your neighbors.

KLJUCO: Coming from Bosnia, Sarajevo Haggadah is kind of a symbol of co-existence, a symbol of caring for the culture that is also your culture, but also culture of your neighbors. A book is more than the sum of its materials. It is an artifact of the human mind and hand. The gold beaters, the stone grinders, the scribes, the binders, those are the people I feel most comfortable with. Sometimes, in the quiet, these people speak to me. They met me see what their intentions were, and it helps me do my work. I worried that the kustos, with his well-meaning scrutiny, or the cops, with the low chatter of their radios, would keep my friendly ghosts at bay. And I needed their help. There were so many questions.

A book is more than the sum of its materials. It is an artifact of the human mind and hand. The gold beaters, the stone grinders, the scribes, the binders, those are the people I feel most comfortable with. Sometimes, in the quiet, these people speak to me. They met me see what their intentions were, and it helps me do my work. I worried that the kustos, with his well-meaning scrutiny, or the cops, with the low chatter of their radios, would keep my friendly ghosts at bay. And I needed their help. There were so many questions.