LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: For the past 30 years, Paul Feldman has been making a living getting up long before the sun rises. It’s an unlikely livelihood for a Cornell- and MIT-educated economist who quit a lucrative Washington research career to deliver bagels. He also delivers donuts, but he’s known as the bagel man. His friends were skeptical.

PAUL FELDMAN: You’re delivering bagels? You’re an economist. You’re an executive. You don’t do things like that.

SEVERSON: Well he did, and still does, purchase bagels and donuts from local bakers and then resells them to employees at corporate offices along Washington’s beltway, and he does it on the honor system. In other words, you choose a pastry, you drop what you owe in a box. He’ll pick up the proceeds later in the day. Feldman has kept track and says on average people are honest 92 percent of the time.

FELDMAN: Honesty is, is fundamental to the operation of a society like ours. Some people get by by being crooks and thieves all the time. But most everything we do is a matter of honesty.

FELDMAN: Honesty is, is fundamental to the operation of a society like ours. Some people get by by being crooks and thieves all the time. But most everything we do is a matter of honesty.

SEVERSON: So are we more or less honest than those before us? Do we cheat more or less? Is it more acceptable? Why is there so much cynicism about government and corporate America, particularly Wall Street?

PROFESSOR DAN AREILY (Fuqua School of Business, Duke University): Wall Street is like a perfect storm of justification. All the things that allow people to justify are in there, and therefore it allows people to think of themselves as good, honorable people while behaving in terribly disgraceful ways.

SEVERSON: Dan Ariely is a professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University who has done experiments on honesty and cheating all over the world, and he says cheating unchecked is contagious.

AREILY (speaking at a Games for Change Conference): The moment you come to an organization that you feel something is wrong with it, all of a sudden your moral shackles go away. What we find is that when people are thinking about honesty versus dishonesty, they don’t do the cost-benefit analysis. They don’t say, “What do I stand to gain? What do I stand to lose?” No. It’s all about being able, at the moment, to rationalize something and make yourself think that this is actually okay. Everybody else is doing this. This is actually the right thing—things like nobody’s really suffering.

SEVERSON: There was a survey recently with 250 investment bankers, portfolio managers, and traders. The results were not encouraging. One in four said they would trade on inside information if they could get away with it. Over half said their competitors engage in unethical or illegal activities. Listen to this: Twenty-four percent say they fear retaliation if they report wrongdoing within their company. Bad corporate behavior is nothing new. One of the most infamous incidents occurred in 1970 with the Ford Pinto, which exploded in car crashes because of the location of the gas tank, killing many people. Lee Iacocca was the Ford CEO at the time. Ann Tenbrunsel is a business professor at Notre Dame.

SEVERSON: There was a survey recently with 250 investment bankers, portfolio managers, and traders. The results were not encouraging. One in four said they would trade on inside information if they could get away with it. Over half said their competitors engage in unethical or illegal activities. Listen to this: Twenty-four percent say they fear retaliation if they report wrongdoing within their company. Bad corporate behavior is nothing new. One of the most infamous incidents occurred in 1970 with the Ford Pinto, which exploded in car crashes because of the location of the gas tank, killing many people. Lee Iacocca was the Ford CEO at the time. Ann Tenbrunsel is a business professor at Notre Dame.

PROFESSOR ANN TENBRUNSEL (University of Notre Dame, Mendoza College of Business, Ethical Institute for Business Worldwide): So if we go back to Iacocca, one of the famous quotes that is mentioned frequently is “safety doesn’t sell.” So if you hear that over and over again, you’re a 22-year old in an organization, your first job, suddenly safety just doesn’t become part of your criteria.

SEVERSON: Professor Tenbrunsel is the director Notre Dame’s Ethical Institute for Business Worldwide and consults with corporations. She believes that despite shareholder pressure, CEO’s need to make ethics a fundamental part of the corporate culture and that they need to reward good behavior and not just the bottom line.

TENBRUNSEL: If I were a CEO I’d go down and I’d run focus groups and say, what happened? What are your pressures? Where do you feel the pressure to behave against your values, or what you think the values of this organizations are? They know.

SEVERSON: She says in the long run companies often pay for unethical behavior. Ford paid for it back then. So did Toyota recently. GM is paying for it now.

SEVERSON: She says in the long run companies often pay for unethical behavior. Ford paid for it back then. So did Toyota recently. GM is paying for it now.

TENBRUNSEL: You look at the amount of kind of damaged reputation that occurs in these recalls, right? If you look at the drop in share price, look at the amount it costs simply to fix the problem, you start to see that it actually can pay to be ethical.

SEVERSON: And to attract good workers.

HENRY GIDDINS (Executive MBA Student): I think if you can rise above the crowd in terms of someone who walks with integrity, someone who lives their values every day that allows you to really distinguish yourself.

SEVERSON: As a trained economist, the 82-year-old bagel man has done some research of his own and says his experience is that employees at larger companies tend to cheat a little more than those at smaller firms; and those who work at companies where ethical conduct is emphasized and morale is high are inclined to be more trustworthy.

FELDMAN: I can walk in, people will greet me, they can—they’re walking up and down the halls talking to each other, and by and large I think that those places tend to be more responsive and more honest.

SEVERSON: Professor Ariely says in his book “The Honest Truth about Dishonesty” that we all lie a little bit, even God.

ARIELY: There’s a story that God comes to Sarah, and he says, “Sarah, you’re going to have a son.” And Sarah laughs, and the religious scholars interpret her laughter as saying, “How can I have a son when my husband is so old?” He said, “Don’t worry.” He goes to Abraham, and He says, “Abraham, you’re going to have a son.” And Abraham says, “Did you tell Sarah?” God said, “Yes.” “And what did Sarah said?” And God says, “Sarah said, ‘How can I have a son when I am so old?’” The religious scholars wondered, how could God lie? How could God misrepresent Sarah? And their conclusion was that it was okay to lie for peace at home.

ARIELY: There’s a story that God comes to Sarah, and he says, “Sarah, you’re going to have a son.” And Sarah laughs, and the religious scholars interpret her laughter as saying, “How can I have a son when my husband is so old?” He said, “Don’t worry.” He goes to Abraham, and He says, “Abraham, you’re going to have a son.” And Abraham says, “Did you tell Sarah?” God said, “Yes.” “And what did Sarah said?” And God says, “Sarah said, ‘How can I have a son when I am so old?’” The religious scholars wondered, how could God lie? How could God misrepresent Sarah? And their conclusion was that it was okay to lie for peace at home.

SEVERSON: Professor Ariely is not a religion scholar but says religion does have an impact on honesty and moral behavior, partly because it offers specific rules connected to a higher order.

ARIELY: In one experiment we asked people to try to recall the Ten Commandments. And, by the way, we did this in California and nobody could recall all Ten Commandments, and many of them invented new commandments, which is an interesting topic by itself, but after doing that they didn’t cheat. In fact, even when we take self-declared atheists and ask them to swear on the Bible, they stop cheating.

SEVERSON: Paul, the Bagel Man, says that people are not quite as honest during Christmas and tax time. He’s rarely canceled a client company but, he says, for some reason has had a difficult time with telecom companies.

PAUL FELDMAN: A manager happened to be there one day and said, “Are you—how are you making out?” I said, “Well, the people here, they’re not paying very well.” She said, “They’ll steal toilet paper in here.”

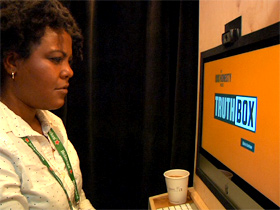

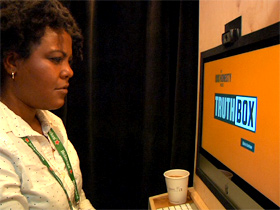

ARIELY: Welcome to the Truth Box. We are trying to understand the complex relationship we have with honest and dishonesty.

ARIELY: Welcome to the Truth Box. We are trying to understand the complex relationship we have with honest and dishonesty.

SEVERSON: Professor Ariely travels with a truth box and asks volunteers to disclose an important lie they have told in their lives, kind of like a confessional box which, he says, helps the confessor behave more morally.

VOLUNTEER: On job interviews if they ask me about certain skills, I would sometimes say that I would have a skill, although I didn’t have the skill at the moment.

ARIELY: How often have you told this particular type of lie?

VOLUNTEER: A couple of times.

ARIELY: And did it work for you? Did they hire you?

VOLUNTEER: Well, yeah, they did.

ARIELY: So now that you told that lie publicly, do you feel better about it?

VOLUNTEER: Well, I’m not going to use it again.

SEVERSON: Professor Tenbrunsel is a practicing Catholic and thinks the concept of a confession would be useful to organizations.

TENBRUNSEL: If in an organization it's one strike and you are out, what is going to be your likely tendency when you discover that you did something wrong, perhaps not intending to, perhaps intending to? Your natural tendency is going to be to cover it up. What does that mean for the organization? It gets hidden. Other people might see it and say, well, gosh, if he’s doing it, it must be okay. Over the long run, that unethical behavior becomes even more detrimental.

SEVERSON: The professor doesn’t think the business and finance world is any more or less ethical than in the past, but she is optimistic that things are going to get better, and not only because of the students. She says she is now seeing genuine interest among corporations to reevaluate their values.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson in Chicago.

FELDMAN: Honesty is, is fundamental to the operation of a society like ours. Some people get by by being crooks and thieves all the time. But most everything we do is a matter of honesty.

FELDMAN: Honesty is, is fundamental to the operation of a society like ours. Some people get by by being crooks and thieves all the time. But most everything we do is a matter of honesty. SEVERSON: There was a survey recently with 250 investment bankers, portfolio managers, and traders. The results were not encouraging. One in four said they would trade on inside information if they could get away with it. Over half said their competitors engage in unethical or illegal activities. Listen to this: Twenty-four percent say they fear retaliation if they report wrongdoing within their company. Bad corporate behavior is nothing new. One of the most infamous incidents occurred in 1970 with the Ford Pinto, which exploded in car crashes because of the location of the gas tank, killing many people. Lee Iacocca was the Ford CEO at the time. Ann Tenbrunsel is a business professor at Notre Dame.

SEVERSON: There was a survey recently with 250 investment bankers, portfolio managers, and traders. The results were not encouraging. One in four said they would trade on inside information if they could get away with it. Over half said their competitors engage in unethical or illegal activities. Listen to this: Twenty-four percent say they fear retaliation if they report wrongdoing within their company. Bad corporate behavior is nothing new. One of the most infamous incidents occurred in 1970 with the Ford Pinto, which exploded in car crashes because of the location of the gas tank, killing many people. Lee Iacocca was the Ford CEO at the time. Ann Tenbrunsel is a business professor at Notre Dame. SEVERSON: She says in the long run companies often pay for unethical behavior. Ford paid for it back then. So did Toyota recently. GM is paying for it now.

SEVERSON: She says in the long run companies often pay for unethical behavior. Ford paid for it back then. So did Toyota recently. GM is paying for it now. ARIELY: There’s a story that God comes to Sarah, and he says, “Sarah, you’re going to have a son.” And Sarah laughs, and the religious scholars interpret her laughter as saying, “How can I have a son when my husband is so old?” He said, “Don’t worry.” He goes to Abraham, and He says, “Abraham, you’re going to have a son.” And Abraham says, “Did you tell Sarah?” God said, “Yes.” “And what did Sarah said?” And God says, “Sarah said, ‘How can I have a son when I am so old?’” The religious scholars wondered, how could God lie? How could God misrepresent Sarah? And their conclusion was that it was okay to lie for peace at home.

ARIELY: There’s a story that God comes to Sarah, and he says, “Sarah, you’re going to have a son.” And Sarah laughs, and the religious scholars interpret her laughter as saying, “How can I have a son when my husband is so old?” He said, “Don’t worry.” He goes to Abraham, and He says, “Abraham, you’re going to have a son.” And Abraham says, “Did you tell Sarah?” God said, “Yes.” “And what did Sarah said?” And God says, “Sarah said, ‘How can I have a son when I am so old?’” The religious scholars wondered, how could God lie? How could God misrepresent Sarah? And their conclusion was that it was okay to lie for peace at home. ARIELY: Welcome to the Truth Box. We are trying to understand the complex relationship we have with honest and dishonesty.

ARIELY: Welcome to the Truth Box. We are trying to understand the complex relationship we have with honest and dishonesty.