KIM LAWTON, correspondent: More than two thousand people make the trek each year to the woods of rural North Carolina for four days of camping, community, song, and prayer. Some call it the “Christian Woodstock.”

GARETH HIGGINS (Founding Director, Wild Goose Festival): Wild Goose is a festival at the intersection of justice, spirituality, music, and art rooted in the Christian tradition, open to everybody, mostly focused on learning how to love.

LAWTON: The name “Wild Goose” comes from the ancient Celtic Christian symbol for the Holy Spirit, and the founders of Wild Goose took their inspiration from other large-scale events, such as the annual Greenbelt Festival, held in England for the past forty years. They felt something similar was needed in the US.

REV. ROSA LEE HARDEN (Producer, Wild Goose Festival): I am very frustrated when I hear Jesus’ words interpreted the way the “cultural Christian” in this country is interpreting them.

REV. ROSA LEE HARDEN (Producer, Wild Goose Festival): I am very frustrated when I hear Jesus’ words interpreted the way the “cultural Christian” in this country is interpreting them.

HIGGINS: Some of us certainly discern that institutional religion in the United States, in its dominant forms, has got it entirely the wrong way around. This is just a place where we are trying to get it more right—or less wrong—through conversation, through experimentation, through allowing the freedom for people to have uncensored dialogue with each other.

LAWTON: Stages and venues for poetry, song, music, dance, and visual arts projects all encourage participants to share their personal stories in a respectful but open way.

HIGGINS: When you have four days in a field, and you’re camping, you stop caring what you look like after a while. And when you stop caring what you look like, or what you smell like, you might let your guard down just a little bit more than in everyday life and have a different kind of conversation than is possible elsewhere.

HARDEN: We encourage people to have conversations across different communities, you know, Baptists and Methodists and Episcopalians and Roman Catholics—they’re all a part of what this is, and we bring other voices in to speak to that conversation as well.

LAWTON: Speakers include authors, theologians, and business leaders. They forgo all appearance fees, as do the artists and performers at Wild Goose.

HIGGINS: There’s no VIP Green Room, and we have people who’ve won Oscars and Grammys and New York Times best-selling authors. You’re more likely to have a meaningful interaction with a really famous person at Wild Goose than you will at other places.

HIGGINS: There’s no VIP Green Room, and we have people who’ve won Oscars and Grammys and New York Times best-selling authors. You’re more likely to have a meaningful interaction with a really famous person at Wild Goose than you will at other places.

LAWTON: Though festival-goers may have varying backgrounds and thoughts on who or what Jesus is, workshops focus on areas of importance to a wide spectrum of people of faith—racial and social justice, diversity, immigration reform, hunger, environmental conservation, and peace.

Singing: “How can so much plenty be based in so much waste?”

JONATHAN WILSON-HARTGROVE (Author and Speaker): There’s a deep longing for a way-of-life faith.

LAWTON: Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove is an evangelical Christian and founding member of the New Monasticism movement.

WILSON-HARTGROVE: New Monasticism is one way of describing the movement towards community, towards simplicity, and towards living nonviolently in our culture. What is church going to look like fifty years from now? I think what everybody agrees on is that something’s in flux. And I think monasticism is one way that we can imagine a future together.

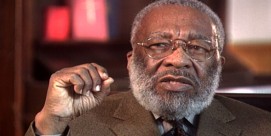

LAWTON: One important voice that will be missed in that conversation going forward: civil rights leader Vincent Harding, who died this year. As a speaker, mentor, and regular attendee, Dr. Harding, a devout Christian, was an integral part of the Wild Goose community since the inception of the festival in 2011.

DR. VINCENT HARDING: I think that churches have a great opportunity and a great responsibility to find the ways to bring us together, not just to “worship together,” but to live together and share our characters with each other.

DR. VINCENT HARDING: I think that churches have a great opportunity and a great responsibility to find the ways to bring us together, not just to “worship together,” but to live together and share our characters with each other.

HARDEN: We sometimes find people who are not culturally Christians, who weren’t raised in Christian families, who follow other faiths more deeply understand the message of Jesus than sometimes we do.

Ani Zonneveld: The song that I'm going to sing for you is called "Prayer of Light."

LAWTON: Singer-songwriter Ani Zonneveld is a co-founder of Muslims for Progressive Values, which advocates for issues like free speech, gender equality, and diversity.

ANI ZONNEVELD (Musician): Jesus was a revolutionary. So was Prophet Muhammad. The values of Christianity and all the three faiths—essentially it’s about caring for our fellow brothers and sisters. It’s very simple.

Ani Zonneveld singing: "Oh Allah, grant me light in my heart. Amen..."

ZONNEVELD: I use music as a tool because it really touches people. The arts, music, the vocal—the singing voice is such a powerful tool. And I use that in a loving way to break down those barriers and to soften the heart. You have to have that security of knowing your faith for you to be so liberated to be open-minded about something else. We are here to learn from each other, and we have different paths—but so what?

LAWTON: Many who’ve been part of it say experiences at Wild Goose can have a profound spiritual impact.

HIGGINS: Someone connected with Wild Goose told me a story that changed my fear of death. There was a period in my life when I was completely secure. I was in a cave for about nine months up until I was born. I was absolutely confident that everything was fine because I knew no alternative. And then suddenly one day I was propelled down a tunnel. It must have felt like suffocating. It must have been absolutely terrifying. Getting born must have felt a little bit like dying. And if that's the case, then one of the stories we can tell at Wild Goose, whether you're from a Christian tradition or not, whether you're a religious person or not, is there's really no need to fear death because it's already happened to you once before. And it turned out to be better than what you expected.

LAWTON: I’m Kim Lawton, reporting.

REV. ROSA LEE HARDEN (Producer, Wild Goose Festival): I am very frustrated when I hear Jesus’ words interpreted the way the “cultural Christian” in this country is interpreting them.

REV. ROSA LEE HARDEN (Producer, Wild Goose Festival): I am very frustrated when I hear Jesus’ words interpreted the way the “cultural Christian” in this country is interpreting them. HIGGINS: There’s no VIP Green Room, and we have people who’ve won Oscars and Grammys and New York Times best-selling authors. You’re more likely to have a meaningful interaction with a really famous person at Wild Goose than you will at other places.

HIGGINS: There’s no VIP Green Room, and we have people who’ve won Oscars and Grammys and New York Times best-selling authors. You’re more likely to have a meaningful interaction with a really famous person at Wild Goose than you will at other places. DR. VINCENT HARDING: I think that churches have a great opportunity and a great responsibility to find the ways to bring us together, not just to “worship together,” but to live together and share our characters with each other.

DR. VINCENT HARDING: I think that churches have a great opportunity and a great responsibility to find the ways to bring us together, not just to “worship together,” but to live together and share our characters with each other.