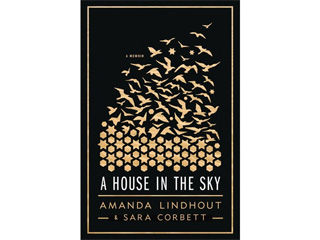

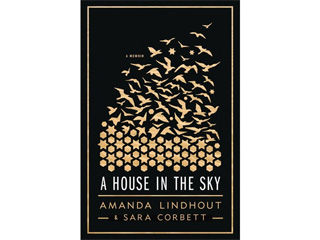

Read excerpts from A House in the Sky by Amanda Lindhout and Sara Corbett.

BOB FAW, correspondent: Listening to her now speaking to an audience on Long Island, or watching her signing copies of her best-selling memoir, one can hardly believe how Amanda Lindhout survived 462 days as a kidnap victim in Somalia, much less how she was transformed.

AMANDA LINDHOUT (to event audience): The things that happened to me during those last ten-and-a-half months in captivity, they’re experiences no human being on the planet should have to go through. Mine is nothing if not a story of survival.

FAW: A Canadian, Lindhout longed to see the world, and on a shoe string budget backpacked in more than fifty countries.

(to Lindhout): You had a kind of wanderlust, but was there a spiritual longing there or a curiosity? Is that the better word?

LINDHOUT: Oh, definitely. I refer to myself in my early twenties as a spiritual seeker.

LINDHOUT: Oh, definitely. I refer to myself in my early twenties as a spiritual seeker.

FAW: In 2008 Lindhout, then twenty-seven, a freelance journalist and photographer, and fellow adventurer, Australian photographer Nigel Brennan, went to Somalia.

As captured in the film Black Hawk Down, Somalia—riven by twenty years of civil war—was not just impoverished, but also almost completely lawless. On their way to do a story about a refugee camp, a band of teenagers toting AK-47s seized the group and demanded a ransom of three million dollars.

LINDHOUT: I found myself lying face down on the dirt, spread-eagle, with a gun held to the back of my head. Our kidnappers told us they were going to kill us. They told us that they would behead us if the money wasn’t paid.

FAW: In her book, Lindhout talks about converting to Islam during her captivity and reading the Qur’an multiple times.

(to Lindhout): You say, “It wasn’t surrender, and it wasn’t defiance. This was”—this is to Islam—“this was simply a chess move. We were doing what it took to survive.”

LINDHOUT: The conversion to Islam was a survival strategy. What I wanted out of it was to understand what motivated my captors. They believed that we were enemies and that based on these particular passages in the Qur’an that it was justified under Islamic law then to abduct us and ask for a ransom.

FAW: Using what she learned in the Qur’an, she pleaded for her freedom.

FAW: Using what she learned in the Qur’an, she pleaded for her freedom.

(to Lindout): You said, “I am your Muslim sister. You have to help me. Allah says Muslims have to help one another.”

LINDHOUT: Well, Muslims have the belief that everything is preordained, and so, therefore, I was exactly where I was supposed to be at that moment in time. The more I came to understand how literally they take it that everything is preordained, I realized that I couldn’t argue with them about this being wrong, what they were doing was wrong.

FAW: Briefly, Lindhout and Brennen tried to escape, fleeing to a local mosque where a single woman tried to help.

LINDHOUT: When Nigel and I ran in, our captors ran in right behind us with guns, so the danger, the real dangers that existed that day makes what that woman did at the mosque is all the more remarkable because that woman, she saw a stranger, a woman in need of help, and she just reacted and she came directly over to me and embraced me and called me her sister, and she did everything she could that day, putting her own life on the line to try to help me.

FAW: Recaptured, her kidnappers made her life almost unbearable.

LINDHOUT: I couldn’t move, because my captors had wound a thick metal chain around my ankles, which they secured with heavy padlocks which remained on my ankles for the next ten-and-a-half months.  I couldn’t sit up. I couldn’t even lie on my back. I could lie only on my side on this very thin, filthy foam mat on the floor in the dark for twenty-four hours a day.

I couldn’t sit up. I couldn’t even lie on my back. I could lie only on my side on this very thin, filthy foam mat on the floor in the dark for twenty-four hours a day.

FAW: Lindhout was repeatedly abused, nearly starved, and in excruciating pain.

LINDHOUT: I just couldn’t understand how people could be capable of reaching those kinds of depths to inflict that kind of suffering on another human being, and I became consumed by anger and confusion and self-pity and rage.

FAW: You flirted with the idea of suicide. You had a razor; you could have. Why didn’t you?

LINDHOUT: I had this unbelievable experience that probably almost sounds like I’m making it up. It was a spiritual experience that absolutely changed everything for me. As I looked over towards the door, there was this little brown bird hopping around in this square of light. And I hadn’t seen a bird in a year. And this bird, to me, was a messenger to hold on. All of the desire to end my own life left me in that moment, and I became fueled by this desire to continue to live, to choose life no matter what they were going to do to me.

FAW: From that point on, as described in her book, it wasn’t just her willpower, but her imagination which helped Amanda Lindhout to go on.

LINDHOUT (reading from her book): In my mind I built stairways. At the end of the stairways I imagined rooms.

FAW: And because of that imaginary house in the sky, because of what she could envision, Amanda Lindhout was able to endure.

FAW: And because of that imaginary house in the sky, because of what she could envision, Amanda Lindhout was able to endure.

LINDHOUT: It was essentially a place that I could go in my own mind to escape my daily reality, and so in my house in the sky it was everything from remembering the life that I had lived and so recreating trips that I had been on in the finest detail to imaging what it would be like to sit around a table and share a meal with my family. The more I used these practices, like going to my house in the sky, the easier it became. And believe it or not, I could close my eyes and escape my reality, and I could even—I could smile at a nice memory, I could laugh at remembering a joke.

FAW: Now, looking back on that terrible ordeal, Lindhout remembers another turning point as she was being assaulted by two of her captors.

LINDHOUT: I remember it so clearly looking down on those three people on the floor, one of whom was me, and the two young men, teenagers who were torturing me and hurting me, and so it surprises people to hear me say there was a sense of compassion that I had for the fact that those young men were the perpetuators of violence, that they were also the victims of it. And this is not Stockholm syndrome, and I am not saying that they were innocent at all, but that is just the truth of the situation.

FAW: And at that point, she would write, “I began to nurture something I’d never expected to feel in captivity, a feeling of compassion for those boys.”

LINDHOUT: Physically I was in chains on the floor and I had no power, no control over that, but I still had the power to choose my response to what was happening to me, to hold on to my own morals and my own values. I knew somehow at the deepest part of my being that if I chose forgiveness, that experience just would not have the power to crush me.

LINDHOUT: Physically I was in chains on the floor and I had no power, no control over that, but I still had the power to choose my response to what was happening to me, to hold on to my own morals and my own values. I knew somehow at the deepest part of my being that if I chose forgiveness, that experience just would not have the power to crush me.

FAW: Lindhout still wrestles with hatred and anger, as she did in captivity. But then and now she tries to choose forgiveness.

LINDHOUT: Of course I was angry for everything that was happening to me, but as time went on in captivity, I just realized for my own self, for self-preservation, that I couldn’t stay trapped in that emotion, that I had to try to find ways to let it out, and that’s when I started developing practices like choosing forgiveness in captivity.

FAW: You said the mind, at one point—and this is, I think, when your hands and your feet were bound—the mind almost became muscular, you say. But you also said you didn’t know whether that was a survival tool or a glimpse of lunacy.

LINDHOUT: Right. When I was alone for the first time, so really alone for the first time in my life, I remember that being the period where I was absolutely terrified of losing my mind. But the more time that I spent alone, I mean, I had 13 months in captivity alone, the mind became very, very strong, and that’s what I mean when I refer to it as muscular. The more that I used these practices, like going to my house in the sky, the easier it became.

FAW: Finally, she was released after a ransom of $300,000 was paid by Lindhout’s and Brennen’s parents. She has spent the last four years recovering and writing her book and starting a foundation, raising over three million to help suffering people in of all places, Somalia.

LINDHOUT: This work has really become my life. It’s what I call compassion in action and it’s really all about the choice that I make every day to forgive that allows me to step into this work.

FAW: Now thirty-three and enrolled in a Canadian university, she still has dark moments and wrestles with PTSD from an ordeal which has left her both wounded and stronger.

LINDHOUT: I pray many times in a day now, and for me now my prayers are very, very different. They’re more like a statement of gratitude for everything that I have, for my freedom now, for the ability to experience the beauty of the world again. I’m really profoundly grateful for that, and I think it’s really important to express that.

FAW: Amanda Lindhout, traveling from darkness into light and from a house in the sky to an inner peace. For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly this is Bob Faw in New York.

Excerpts from A House in the Sky

Islam was everywhere in Dhaka. On the mirror in my room was a small arrow-shaped sticker helpfully pointing the way toward Mecca. Five times a day, the muezzins chanted and the prayers began. These moments were strangely private and public at the same time. The men in my hotel lobby, guests and employees, arranged themselves into lines and bowed in unison, unaware of or unruffled by my presence. People, mostly men, were praying in the streets, outside of the mosques, which were often too small to hold everyone, especially on Friday, the Islamic holy day. I thought it was beautiful. The repeated bowing, the rows and rows of people humbled before God. After the bowing, they sat with their hands cupped in front of their faces in supplication, whispering a finish to their prayers. It was so foreign to me, a religion that required so much from its believers, this display of devotion every few hours.

Islam was everywhere in Dhaka. On the mirror in my room was a small arrow-shaped sticker helpfully pointing the way toward Mecca. Five times a day, the muezzins chanted and the prayers began. These moments were strangely private and public at the same time. The men in my hotel lobby, guests and employees, arranged themselves into lines and bowed in unison, unaware of or unruffled by my presence. People, mostly men, were praying in the streets, outside of the mosques, which were often too small to hold everyone, especially on Friday, the Islamic holy day. I thought it was beautiful. The repeated bowing, the rows and rows of people humbled before God. After the bowing, they sat with their hands cupped in front of their faces in supplication, whispering a finish to their prayers. It was so foreign to me, a religion that required so much from its believers, this display of devotion every few hours.

As a traveler, I was formulating an edge that would help me in years to come—finding and holding the line between the pleased-to-meet-you openness that both served backpackers and made them easy prey, and a more aggressive way of using my own power. Without the language or a way to pick up cultural cues, it could be hard to parse opportunity from danger. Your mind always had to be thinking a move or two ahead. I believe I was good at this, for the most part. I’d spent enough of my childhood trying to read cues and navigate uncertainty. Uncertainty was what I knew…

*

In my mind, I build stairways. At the end of the stairways, I imagined rooms. These were high, airy places with big windows and a cool breeze moving through. I imagined one room opening brightly onto another room until I’d built a house, a place with hallways and more staircases. I built many houses, one after another, and those gave rise to a city—a calm, sparkling city near the ocean, a place like Vancouver. I put myself there, and that’s where I lived. In the wide-open sky of my mind….I made peace with anyone who might ever have been an enemy. I asked forgiveness for every vain or selfish thing I’d done in my life. Inside the house in the sky, all the people I loved sat down for a big holiday meal. I was safe and protected. It was where the voices that normally tore through my head expressing fear and wishing for death went silent, until there was only one left speaking. It was a calmer, stronger voice, one that to me felt divine.

It said, See? You are okay, Amanda. It’s only your body that’s suffering, and you are not your body. The rest of you is fine.

—From “A House in the Sky” by Amanda Lindhout and Sara Corbett (Scribner, 2013).

LINDHOUT: Oh, definitely. I refer to myself in my early twenties as a spiritual seeker.

LINDHOUT: Oh, definitely. I refer to myself in my early twenties as a spiritual seeker. FAW: Using what she learned in the Qur’an, she pleaded for her freedom.

FAW: Using what she learned in the Qur’an, she pleaded for her freedom. I couldn’t sit up. I couldn’t even lie on my back. I could lie only on my side on this very thin, filthy foam mat on the floor in the dark for twenty-four hours a day.

I couldn’t sit up. I couldn’t even lie on my back. I could lie only on my side on this very thin, filthy foam mat on the floor in the dark for twenty-four hours a day. FAW: And because of that imaginary house in the sky, because of what she could envision, Amanda Lindhout was able to endure.

FAW: And because of that imaginary house in the sky, because of what she could envision, Amanda Lindhout was able to endure. LINDHOUT: Physically I was in chains on the floor and I had no power, no control over that, but I still had the power to choose my response to what was happening to me, to hold on to my own morals and my own values. I knew somehow at the deepest part of my being that if I chose forgiveness, that experience just would not have the power to crush me.

LINDHOUT: Physically I was in chains on the floor and I had no power, no control over that, but I still had the power to choose my response to what was happening to me, to hold on to my own morals and my own values. I knew somehow at the deepest part of my being that if I chose forgiveness, that experience just would not have the power to crush me. Islam was everywhere in Dhaka. On the mirror in my room was a small arrow-shaped sticker helpfully pointing the way toward Mecca. Five times a day, the muezzins chanted and the prayers began. These moments were strangely private and public at the same time. The men in my hotel lobby, guests and employees, arranged themselves into lines and bowed in unison, unaware of or unruffled by my presence. People, mostly men, were praying in the streets, outside of the mosques, which were often too small to hold everyone, especially on Friday, the Islamic holy day. I thought it was beautiful. The repeated bowing, the rows and rows of people humbled before God. After the bowing, they sat with their hands cupped in front of their faces in supplication, whispering a finish to their prayers. It was so foreign to me, a religion that required so much from its believers, this display of devotion every few hours.

Islam was everywhere in Dhaka. On the mirror in my room was a small arrow-shaped sticker helpfully pointing the way toward Mecca. Five times a day, the muezzins chanted and the prayers began. These moments were strangely private and public at the same time. The men in my hotel lobby, guests and employees, arranged themselves into lines and bowed in unison, unaware of or unruffled by my presence. People, mostly men, were praying in the streets, outside of the mosques, which were often too small to hold everyone, especially on Friday, the Islamic holy day. I thought it was beautiful. The repeated bowing, the rows and rows of people humbled before God. After the bowing, they sat with their hands cupped in front of their faces in supplication, whispering a finish to their prayers. It was so foreign to me, a religion that required so much from its believers, this display of devotion every few hours.