LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: After his brother died, Clifford Hayes was homeless, so he went to the sheriff’s office for permission to stay at a Salvation Army shelter for one night.

CLIFFORD HAYES: I didn’t know they had a warrant for my arrest. I went there to go get me a shelter clearance, and they locked me up.

SEVERSON: The warrant was for a speeding ticket he’d received several years earlier. A private probation company appointed by the court said the fine had not been paid. Hayes says the fine, plus the company’s fees, had ballooned to a couple thousand dollars—money he didn’t have.

(to Hayes): Have you been in any other trouble besides the speeding ticket?

HAYES: No sir, no sir.

SEVERSON: That’s it?

SEVERSON: That’s it?

HAYES: That’s it.

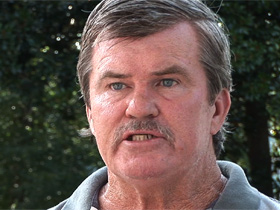

JACK LONG: I was shocked that he would be in jail and supposedly would have stayed in jail for a year or two on these charges.

SEVERSON: Jack Long is a self-proclaimed conservative Republican attorney in Augusta, Georgia who is representing several probationers free-of-charge. He is outraged because he says a 1983 Supreme Court case ruled that people on probation cannot be jailed because they can’t afford to pay a fine. Caroline Isaacs is with the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization.

CAROLINE ISAACS (American Friends Service Committee): These are folks that in many cases couldn’t pay like a two hundred dollar fine or ticket. They’re put on probation. They have to pay interest on what they owe, and they have to pay that company for the privilege of being supervised by them. It’s like a payday loan they end up paying ten times over, and these are people that are poor to begin with.

SEVERSON: Chris Albin-Lackey is with Human Rights Watch. He authored an extensive report called “Profiting from Probation.”

CHRIS ALBIN-LACKEY (Human Rights Watch): The issue is that the courts are hiring these people not really to act as probation officers, but to act as debt collectors. The fact that they’re called probation officers is in many courts really nothing more than a legal fiction. It’s not just, it’s not ethical and it’s not in keeping with people’s basic rights.

HAYES: These are my bills that I have to pay now. These are brand new bills. Hospital bills, medical bills.

HAYES: These are my bills that I have to pay now. These are brand new bills. Hospital bills, medical bills.

SEVERSON: Clifford Hayes has lupus, a disease that has taken three members of his family. He receives a monthly supplemental security income check, SSI, for $720. His rent is $400. His medication costs at least $70 a month. He lives in fear that he’ll be jailed again for the old speeding ticket if Jack Long is not there to protect him.

LONG: If someone violates the rules of society they need to be punished. But the punishment needs to have some—if it’s going to be based on a fine it has to be based on the person’s ability to pay. If they don’t have the ability to pay, they can pick up trash on the streets, or they can have some community service.

SEVERSON: Jack Long says his probation cases have all been with the for-profit company called Sentinel Offenders Services, but there are many other private probation companies out there.

LONG: I have learned it’s a lot more widespread than I ever thought, and the abuses are more prevalent than I ever thought.

SEVERSON: We requested an interview with the sheriff of Richmond County here in Augusta, but we’re told that Sheriff Roundtree had no comment. We contacted Sentinel Offender Services for the company side on this issue and have not heard back. In previous public statements, Sentinel officials have said that their supervision helps offenders meet the terms of their probation. Sentinel also offers English-as-a-second-language classes and guidance counseling.

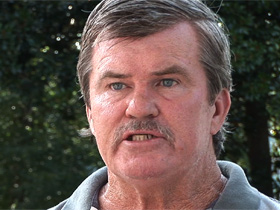

Tom Barrett has no gripe with Sentinel, and he was under their supervision for longer than he would care to remember.

TOM BARRETT: Sentinel, now they were professional, and I didn’t really have a problem. They were doing their job.

TOM BARRETT: Sentinel, now they were professional, and I didn’t really have a problem. They were doing their job.

LONG: Thomas Barrett is an individual that had a college education. He was a pharmacist by training, he was in the army, he—life was going on with him, and unfortunately he had an alcohol problem.

BARRETT: And I was real depressed, and I just said, you know, I want a beer, and I walked by this convenience store, and I walked in there.

SEVERSON: So Barrett was arrested for shoplifting a $2 can of beer.

LONG: He was incarcerated, and the judges told him he would have to go on electronic monitoring if he wanted to be released from jail.

SEVERSON: Electronic monitoring costs about $12 a day, and he would have to install a land-line in his home for the monitor to work—all requiring money he didn’t have.

BARRETT: Basically, they said I was going to be locked up until I could make all these arrangements, and I’m thinking, if I’m locked up its going to be more difficult to make these arrangements, plus I have no money.

SEVERSON: Finally, a friend convinced the judge to allow him out of jail long enough to make enough money to stay out of jail.

BARRETT: My only income was food stamps and selling plasma, so I was falling behind, and the probation officer said when you get up to about five hundred dollars behind, you get locked up again. And so I got five hundred dollars behind, and I got locked up again.

BARRETT: My only income was food stamps and selling plasma, so I was falling behind, and the probation officer said when you get up to about five hundred dollars behind, you get locked up again. And so I got five hundred dollars behind, and I got locked up again.

SEVERSON: Altogether he was locked up three times.

LONG: I know that jailing cost fifty dollars a day, and I think he was probably in jail for at least 60 days or 70 days, so probably over thirty-five-hundred dollars.

SEVERSON: The cost for his jailing was passed on to the taxpayers.

ALBIN-LACKEY: A lot of courts don’t have the funds to pay for their own operations. A lot of courts are under tremendous pressure from local public officials not to be a burden on the taxpayer, to generate revenue instead of costing revenue.

SEVERSON: Caroline Isaacs says local courts are turning to private for-profit companies to save money. More than five million Americans are on probation.

(to Isaacs): But aren’t they saving the taxpayers money?

ISAACS: I have seen no evidence of that thus far.

SEVERSON: It’s estimated that private probation companies in Georgia alone collect fees of over $40 million annually.

LONG: I’m surprised it’s that low. I think it’s higher than that.

SEVERSON: Higher than $40 million?

LONG: Yes, and I don’t think you can know, because they don’t disclose. They’re not required to disclose everything they collect.

ALBIN-LACKEY: A lot of companies provide quarterly bonuses to their employees based on how much money they take in, and I think that’s a perfect example of how these probation officers who work for these private companies are often being explicitly pushed in the direction not of being probation officers in the traditional sense of the term, but in just being very effective at squeezing money out of the people who come into their offices.

LONG: They have an incentive to basically keep people on probation as long as possible, to sell as many services as they can.

SEVERSON: Caroline Isaacs says faith groups that have been involved in incarceration-for-profit issues are now taking a closer look at for-profit probation.

ISAACS: Even beyond, you know, the basic ethical conundrum of incarceration for profit there are other fundamental faith principles. Redemption and forgiveness really are falling by the wayside when we profitize these functions.

SEVERSON: Jack Long is taking 13 probation cases against Sentinel before the Georgia Supreme Court. If he wins, it could severely restrict the profits of companies like Sentinel.

LONG: The judicial branch of government does not need to be involved in helping a company make a profit.

SEVERSON: Among the cases before the court are Clifford Hayes and Tom Barrett, who has quit drinking for over six months.

BARRETT: I’m ashamed of what I did. I made a mistake, but I need to move on.

SEVERSON: Tom Barrett says he forgives the people who have given him such a hard time, but cannot forgive the system.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I'm Lucky Severson in Augusta, Georgia.

SEVERSON: That’s it?

SEVERSON: That’s it? HAYES: These are my bills that I have to pay now. These are brand new bills. Hospital bills, medical bills.

HAYES: These are my bills that I have to pay now. These are brand new bills. Hospital bills, medical bills. TOM BARRETT: Sentinel, now they were professional, and I didn’t really have a problem. They were doing their job.

TOM BARRETT: Sentinel, now they were professional, and I didn’t really have a problem. They were doing their job. BARRETT: My only income was food stamps and selling plasma, so I was falling behind, and the probation officer said when you get up to about five hundred dollars behind, you get locked up again. And so I got five hundred dollars behind, and I got locked up again.

BARRETT: My only income was food stamps and selling plasma, so I was falling behind, and the probation officer said when you get up to about five hundred dollars behind, you get locked up again. And so I got five hundred dollars behind, and I got locked up again.