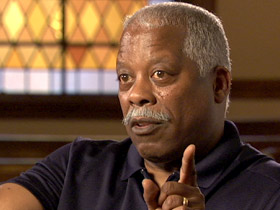

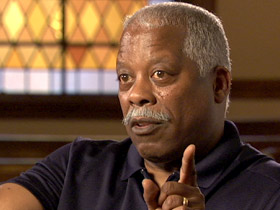

DAN LOTHIAN, contributing correspondent: In Boston's gritty inner city, Reverend Eugene Rivers...

REV. EUGENE RIVERS: (on the street) Hey, what's up baby?

Man: Long time, Rev.

REV. RIVERS: How you doing playah?

LOTHIAN: …is driven by optimism. One more life rescued from the streets.

REV. RIVERS: See, only faith gives you the ability to look at a mountain and see it as an opportunity. For people without faith, a mountain is an obstacle. For people with the eyes of faith, a mountain is an opportunity.

LOTHIAN: Boston once had a very big volcanic mountain that erupted in the late 80's and early 90's. An epidemic of murder some called it. More than 150 victims in one year alone. There was no trust between the community and cops. It was a time of guns, gangs and drugs.

This Harvard-educated minister moved in to what he calls ground zero and quickly learned about street justice.

REV. RIVERS: He jumped out. Pow! Pow! Pow!

LOTHIAN: A young gang member angry at the minister's efforts to clean up a trouble spot fired shots into his home. Rivers and his family were inside but were unharmed.

(to Rev. Rivers): That was a real moment?

REV. RIVERS: Oh, that was a real test.

LOTHIAN: It was a test for the city as well. Like the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, mistrust and anger collided in Boston. Law enforcement was failing, even refusing to admit that gangs were in town.

REV. RIVERS: There appeared to be no rules and the politicians, the secular politicians, had no idea what to do with something which in their historical memory had no precedent.

LOTHIAN: Then against all odds the shadow of Boston's big mountain began to fade. Reverend Rivers along with other inner city ministers founded the Ten Point Coalition, an organization that targets at-risk youth. They also began laying the foundation for trust between skeptical residents and the police.

It didn't happen overnight. Little by little, Boston started chipping away at its crime rate. More police officers hit the streets, but part of the solution was the church—pastors who spent more time out on the streets than they did behind the pulpit.

Reverend Bruce Wall, then a youth pastor who often teamed up with Rivers, started hanging out at Chez Vous, a rollerskating rink that at the time was popular with gang members. He was aiming for their minds and their souls.

REV. BRUCE WALL (Pastor, Global Ministries Christian Church): My wife would watch the TV news and say, "Oh, a fight broke out again at Chez Vous roller skating rink," and she said, "Aye yai yai," but I was earning credibility at the skating rink.

LOTHIAN: By 1999, Boston's murder rate had dropped by nearly 80%. The police department was more ethnically diverse. Federal dollars started pouring in, a recognition that the partnership with law enforcement and clergy was working.

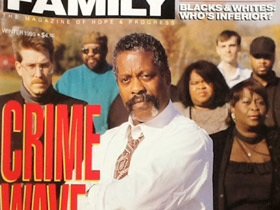

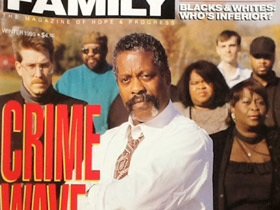

Reverend Rivers landed on the cover of Newsweek Magazine. "God vs. Gangs" it read. That story proclaimed the power of religion as the hottest idea in crime fighting. The turnaround was dubbed "The Boston Miracle."

In the wake of what happened in Ferguson, veterans of Boston's inner-city ministries are reassessing their past.

(to Rev. Rivers): When you look back 20, 25 years ago, what worked?

REV. RIVERS: The partnerships. Clergy doing street patrols at night, working in collaboration with law enforcement, giving young gang-involved members options, right? Listen, I got a carrot and I got a stick, you figure it out. The clergy: minister, mentor, monitor. That was new.

LOTHIAN: Rivers, who recently visited Ferguson, says disaffected men need to be reached early.

REV. RIVERS: What Ferguson could learn from Boston is that the clergy have to engage the young brothers.

(on the street): You don't catch a kid at 13 or 14, no that's too late, you gotta get a kid at 4, 5, 6, 7 in the hood.

LOTHIAN: And ministers or other activists, he says, shouldn't just visit but live among them.

REV. RIVERS: What Ferguson has to do, the churchmen, the clergy of Ferguson, they gotta talk to the dudes that threw those canisters back at the police. They've got to reach out to those alienated young men who are very angry and rightfully so.

LOTHIAN: And the churches have to be willing to put pressure on lawmakers and police when they aren't doing their jobs.

REV. WALL: (on his radio show) I'm Pastor Bruce Wall. I'm gonna be your host tonight.

LOTHIAN: Reverend Wall's "Boston Praise Radio and TV" is an outlet to do just that, hold officials accountable.

REV. WALL: We want to bring them in here and put their backs up against the wall and say to them, "We don't work for you, you work for us. What is it that you say you're going to do?" And then we hold them accountable with a microphone.

(on his radio show): We're going to be talking about Ferguson, Missouri—why they are not as politically active as they should be.

LOTHIAN: Wall says he isn't criticizing the people of Ferguson, just having a constructive conversation.

Boston, he warns, should not gloat.

REV. WALL: People remember what Boston did in the past. Boston is living off of the success of the past. If somebody were to pull the curtain and see that the emperor has no clothes on, we would be exposed for what we are.

LOTHIAN: He's talking about what Boston did not get right. Pastors and other community activists started bickering over federal dollars for their programs. Partnerships unraveled. And…

REV. WALL: Pastors started traveling all over the country and around the world talking about the success in Boston. The problem was that it left nobody in Boston to continue the success.

LOTHIAN: Reverend Rivers says the biggest misstep was the lack of foresight—not looking beyond the victory.

REV. RIVERS: We had not developed a succession plan to find younger clergy who would put boots on the ground. One has to take a long view and have a succession plan as part of your model if you're going to sustain it over a longer period of time.

LOTHIAN: Crime ticked up again, but nowhere near the epidemic of more than two decades ago. Even so, Reverend Wall will soon travel to Chicago, a city confronting its violent crime problem, not to give officials and clergy advice but to see if there are any ominous trends that could be transmitted to Boston.

REV. WALL: I do not want all of this work to be reversed.

RIVERS: (on the street): Hey dear!

Woman: How are you?

RIVERS: Fine, how are you?

LOTHIAN: Rivers still walks these familiar streets, calling out names, pointing to young men he first met when they were in diapers. But there's a new twist: he's also strolling online.

REV. RIVERS: We've gotta be at the park and we've gotta try to track Facebook, to see what kinds of things are going on. There's been a technological revolution and people are buying drugs off the internet, they're texting, they're emailing, right? So the cats doing the doo-wop thing on the corner has shifted because now the social network world is the new street corner.

LOTHIAN: Adjusting to the times in a fight against crime now designed for the long haul.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I'm Dan Lothian in Boston.