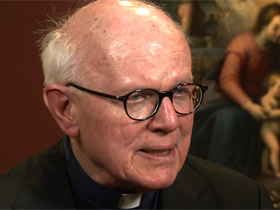

TIMOTHY VERDON (Director of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and Canon of the Florence Cathedral): This is an exhibit about Mary, the mother of Jesus. But, more specifically, it is about the way in which people have seen Mary through the centuries.

The ways of presenting Mary in art change as society evolves. The early Church showed Mary as a kind of goddess, rigid and hieratic, and often splendidly, regally attired. And the Christ Child as the son of such a woman, a little baby emperor as it were.

At the end of the Middle Ages, a new class of people emerged, the urban mercantile class who wanted art that could show them religious subjects in a way that allowed them to feel comfortable.

They didn’t immediately respond to the regal image of Mary; but, Mary as a well-off lady of the upper classes, with a beautiful baby in her arms, allowed them to see their own wives or daughters or mothers. And so we begin to find much more human images of Mary. We see her in dresses that were in fashion in the 14th and early 15th century.

The rich clothing is meant to indicate her importance; but, at the same time, her downcast gaze, in the very contained posture of her body, her actual person is deeply humble and deeply thankful to God. It’s the image of people whose life may be comfortable but who, in their hearts, maintain a kind of spiritual simplicity.

Mary is usually shown with the Christ Child, and in a certain number of these works, even when Christ is still a child, one senses that she is aware of his future suffering and death and her joy in holding the child in her arms is already overshadowed by that future sadness, that tragic fate that awaits her son.

Mary is usually shown with the Christ Child, and in a certain number of these works, even when Christ is still a child, one senses that she is aware of his future suffering and death and her joy in holding the child in her arms is already overshadowed by that future sadness, that tragic fate that awaits her son.

Botticelli gives Mary this deep reflective and even sad appearance, certainly wants us to understand that she is thinking about the child’s future death. And so a later artist puts in the signs of that death. The child has three small nails in his left hand and a crown of thorns.

A marble relief from the Cathedral Museum in Florence shows Mary tickling the baby. The baby is fighting off the tickling hand but loving it. It’s the kind of magical moment of intimacy between a mother and a child which touches everyone.

There’s a marvelous painting by an artist, whose name we don’t know but whom historians call The Master of the Winking Eyes. Winking Eyes because in all of his paintings people are smiling and their eyes seem almost to, to wink at you.

Here, the child has taken Mary’s veil, her humanity, and put it over his head. The mother’s veil over the child’s is a symbol—God’s son took his human nature from Mary, and he covers himself with it. So, at the same time, you have this charming image of a mother and child playing and an image that contemporaries of the artist would have read in these theological terms.

The real-life dimension of familial intimacy is a perfect translation of what Christianity tries to convey to people, namely that God gave such enormous value to every aspect of human life that he chose to share it, even these wonderful and at the same time so fleeting moments.

Mary is usually shown with the Christ Child, and in a certain number of these works, even when Christ is still a child, one senses that she is aware of his future suffering and death and her joy in holding the child in her arms is already overshadowed by that future sadness, that tragic fate that awaits her son.

Mary is usually shown with the Christ Child, and in a certain number of these works, even when Christ is still a child, one senses that she is aware of his future suffering and death and her joy in holding the child in her arms is already overshadowed by that future sadness, that tragic fate that awaits her son.